:quality(100)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thesummit/R3HOK3U46BDLDDEWL5KP6JRV4A.jpg)

The Biden administration has declared monkeypox to be a new “public health emergency” — but the virus is already the subject of old misinformation tactics.

Some of the myths accompanying this latest outbreak are tied to conspiracy theories dating back to the bubonic plague and updated during more modern epidemics: HIV/AIDS, Zika and Ebola, for example. They also benefit from a misinformation infrastructure strengthened throughout two years of the covid-19 pandemic, and from waning trust in health and media institutions.

“I’ve found that epidemic-related misinformation and disinformation is often wildly similar and follows very predictable trends,” said Seema Yasmin, a doctor who directs the Stanford Health Communication Initiative and has researched misinformation during epidemics for more than a decade. “You could just insert ‘name of pathogen,’ basically, and you’ll see these cyclical misinformation trends regarding HIV or covid, or Ebola or monkeypox.”

Monkeypox is a virus in the same family as smallpox. While the origins of this latest outbreak are unknown, the virus originates in wild animals and was first identified in the mid-20th century.

ADVERTISEMENT

But its emergence now has allowed it to become connected to other cultural tropes, including lasting conspiracies about covid-19 and an anti-queer political climate.

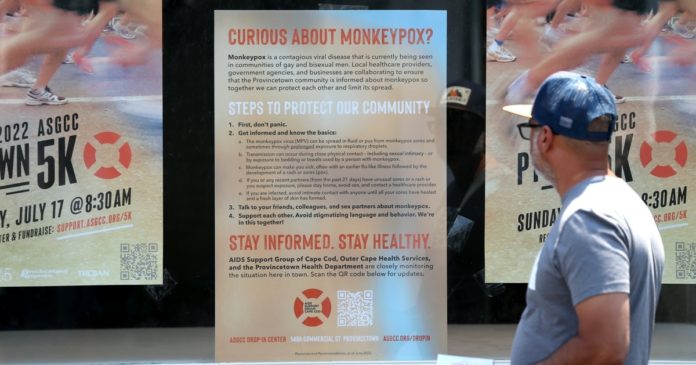

Indeed, one element of monkeypox misinformation echoes misinformation spread during the height of the AIDS crisis. Currently, the population most at risk for exposure is men who have sex with men. Consequently, people — including elected officials — suggest that this makes it a sexually transmitted infection (STI), and one that’s only a problem for gay people. (It’s not — but men who have sex with men are considered at higher risk.)

This can put queer people at risk of being scapegoated — or worse — while also allowing straight people to misunderstand their own risks of contracting the disease.

A medical crisis creates the perfect conditions for misinformation to flourish, said Yasmin.

“You’ve got something scary: check. You’ve got unanswered questions: check. You’ve got people becoming sick: check,” she said. “All of these things are happening that already give people a heightened sense of fear and anxiety, which is a great environment for misinformation and disinformation to spread.”

ADVERTISEMENT

An age-old pattern of medical misinformation

Yasmin sees conspiracies emerging about monkeypox that resemble what she’s heard about other disease outbreaks: “things like, the pathogen is man-made; it’s being deliberately spread; it’s part of a government conspiracy. The treatments are poisonous; the vaccines themselves are toxic.”

That’s the message in some corners online and coming from some public officials. As with covid, some blame the media for hyping up a new and invented crisis.

“People just have to laugh at it, mock it and reject it,” the far-right Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (Ga.) said at a Turning Point USA Student Action Summit in Tampa, Fla., in July. “It’s another scam.”

In new research from the Annenberg Public Policy Center of the University of Pennsylvania, people’s awareness of monkeypox is growing, but their understanding of how the virus functions and spreads is limited.

Two-thirds of respondents are not aware of the existence of a monkeypox vaccine, for example, and only one-third understand that the virus is less contagious than covid.

ADVERTISEMENT

And some respondents either believe, or are not sure about, conspiracy theories. Twelve percent of respondents said monkeypox was likely bioengineered in a lab, and a third of respondents were not sure if that is true. A similar number (14 percent) believe it was intentionally released or are not sure if it was (30 percent).

It’s common for conspiracy theories to get repackaged in the face of a new infectious disease outbreak, said Kathleen Hall Jamieson, the center’s director and co-author of the book “Creating Conspiracy Beliefs: How Our Thoughts Are Shaped.”

“The assumption underlying conspiracy theory is that nothing happens by chance, that there’s always human intent and malevolent design behind things that are having harmful consequences,” she said.

The ongoing experience of covid-19 has shifted the conspiracy landscape, in part by giving other conspiracy theories a reliable anchor point, she added. For example, new medical events can be blamed on the covid vaccine, which has received nearly two years of scrutiny and unfounded attacks.

“Because covid has been such a sustained experience, it increased the likelihood that those conspiracy theories … would have an external stimulus to harness themselves to on a really regular, ongoing basis,” she said. “The conspiracy theories have more opportunity to play on the ongoing anxiety.”

Anti-queer misinformation

Misinformation about monkeypox has taken on one key thread that distinguishes it from covid misinformation: false conclusions about its transmission among men who have sex with men.

Its presence in that community has led to the misconception that it is sexually transmitted, when in fact it is transmitted through any close contact. More damaging is the narrative that it somehow targets queer people exclusively.

On her podcast, Greene dismissed it as an STI harming only gay men who engage in risky sexual behavior.

“Monkeypox is all the rage; it is the hottest thing going in Washington, D.C., right now,” Greene said. “You are not supposed to talk about how it really gets spread around, but we are going to just go ahead and let you know. Yes, it is gay sex orgies. Sorry everybody, that is the truth; it just had to be said.”

As monkeypox spreads beyond that community, therefore, queer people are at risk of being scapegoated. Shortly after it was announced that children had contracted the illness, Greene asked on Twitter, “If Monkeypox is a sexually transmitted disease, why are kids getting it?”

ADVERTISEMENT

It’s a short leap from that question to a connection between queerness and child predation. Indeed, for months, right-wing politicians and public figures have worked to build that connection, using the concept of “grooming” to build legislation targeting sexual education and healthcare for trans children, and even during a Supreme Court confirmation hearing.

Public officials aren’t helping that messaging. Rochelle Walensky, the director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said on July 22 that two child cases of monkeypox “are traced back to individuals who come from the men who have sex with men community — the gay men community.”

According to research conducted for MIT Technology Review by the Center for Countering Digital Hate, such “homophobic misinformation circulating about monkeypox on social media is hampering efforts to curb the disease’s spread.” The research identifies videos and posts viewed tens of thousands of times echoing claims similar to Greene’s.

The scapegoating impulse is predictable and dangerous, said Hall Jamieson, of the Annenberg Center.

“There is a natural human impulse to seek understanding and to blame someone,” she said. After blame, Hall Jamieson added, comes “a narrative that explains that they’ve actually caused it — and hence, by punishing them, you might be able to eliminate it.”

ADVERTISEMENT

One can see the consequences of such messaging by studying the AIDS crisis, said Yasmin. In the early days, the people most at risk included queer people and intravenous drug users. While those communities faced stigmatization, marginalization and blame, straight people and people who did not use drugs enjoyed a false sense of security — “to the point of perhaps even feeling immune to a pathogen that clearly is an equal-opportunity virus.”

“So much of messaging during an acute crisis has to relay the facts in a way that don’t give a false sense of security to those who are not disproportionately affected during that [early] phase of the epidemic,” she added.

Thanks to Lillian Barkley for copy editing this article.