Before the UK decriminalisation of homosexuality (Sexual Offences Act 1967) and technology united LGBT voices, gay life for many men and women was very difficult: either complete denial of your true self or living a double life

One half of this two-part existence often involved speaking a secret language, a jargon of sorts, that many LGBT people used to communicate with each other to avoid detection. This language was called Polari.

Polari had been around for hundreds of years and was a mixture of Italian, Romani and slang from a variety of disparate groups, from circus performers to the merchant navy. The language would substitute some words for others, concealing the meaning of the conversation to outsiders and providing LGBT people with a sort of cloak. It also meant that Queer people could work out if they were in safe company, just like using a secret code.

Queer people could work out if they were in safe company, just like using a secret code.

The use of Polari disappeared after the 1960s as it was no longer essential to the safety of LGBT people in the UK. Programmes like Round the Horne also made Polari public knowledge, so it no longer provided the protection it once did.

Violets exchanged between lesbians was a way to signify romance without revealing identity, an unspoken language popularised firstly in New York. This idea was taken from Eduoard Bourdet’s ‘The Captive’ play in 1927, which told the story of a lesbian couple who send one another posies of violets.

Secret languages and double lives are still a painfully common part of LGBT life, particularly in religiously authoritarian countries or in parts of the world were colonial era anti-sodomy laws still persist. However, for these people, the secret languages of the past have taken a very different shape – today, LGBT voices aren’t hidden by jargon or slang, they’re encrypted.

Social media

Social media has played an increasingly prevalent part in LGBT life since its inception and is vital lifeblood for many of those living in parts of the world where homosexuality is still punishable by law or socially taboo.

In the Republic of Burundi, for example, a country where same-sex sexual activity is criminalised, a lot of lesbian and bisexual women are forced to meet online in order to connect with other members of their community.

In an interview published earlier this year by the BBC, Leila and Neya, a lesbian couple living in Burundi, said this:

“It’s hard to describe how exactly gay people meet each other in Africa. You don’t have a lesbian hotspot that you can Google – a known place we can meet up. You become an expert in picking up vibes from each other, because so much of your communication is nonverbal. You become an expert in body language, eye contact.”

“We don’t have dating apps, but we have social media,” says Niya. “There are certain shorthands there too. A meme we may have picked up from somewhere else, or a coded phrase. Nothing that anyone else outside the lesbian community would ever be able to pick up on.”

Apps

The ubiquity of smartphones has given LGBT people the opportunity to connect to each other. Apps on Android and iOS have granted millions of people who felt unable to speak about their innermost thoughts and feelings the chance to date and forge relationships in places where they previously could not. The role of apps in LGBT life is set to change, however, and as of this year won’t just be a tool used to connect LGBT people but will also be used in the fight against HIV.

North America is currently in the grips of an HIV epidemic that is disproportionately affecting Hispanic and African American young men, and so developers are currently in the process of designing an app that is set for nationwide distribution later this year.

P3, which stands for prepared, protected and empowered, will use everything from gamification techniques to social activities to remind and motivate young people at risk of contracting HIV to take Prep, track their meds, post to a social wall about daily discussion topics and talk to their partners about HIV testing.

The hope is that this app will not only help to remind those at risk to take their medication, but it will also encourage conversation between those in high-risk groups to talk openly about their HIV status.

VPNs

Most people know about virtual private networks because they are frequently used to help those living outside of certain regions to watch streaming services that they couldn’t ordinarily. But for LGBT people living in places like China and Pakistan, VPNs are much, much more: they’re a way to stay safe and protect your identity while maintaining a connection with the local LGBT community.

In an interview with the LA Times, Sun Mo, a 25-year-old media operations manager at the Beijing LGBT Centre, explained why Blued, China’s version of Grindr, is such a big part of so many gay men’s lives:

“Blued is more important for Chinese people than Grindr is for Americans. In America, if you don’t use Grindr, you can go to a gay bar. You can find gay people around. In China, apart from Beijing, Guangzhou and Shanghai — in smaller cities, and in the countryside — you can’t find any gay organisations or gay bars whatsoever.”

Blockchain

Blockchain is one of the latest technologies and is often associated with modern cryptocurrency. Blockchain is challenging the way we do things because it provides an open, decentralised database were the authenticity of things like money, property and even votes can be verified by an entire online community without the need for intermediaries.

Protecting rights through immutable records, such as the land records in Honduras, has sparked a huge fear in the corridors of power. This is because it means the global community is one step closer to removing powerful “men in the middle”, like banks and governments, and could potentially result in citizens soon having greater control over their own money, rights and identity.

the global community is one step closer to removing powerful “men in the middle”, like banks and governments

Christof Wittig, the creator of Hornet, the world’s second largest gay social network, has set up the LGBT Token, a form of cryptocurrency that hopes to help LGBT people better protect their identities in parts of the world where they face persecution, harness the economic clout of the LGBT community and ensure the voices of LGBT people are heard.

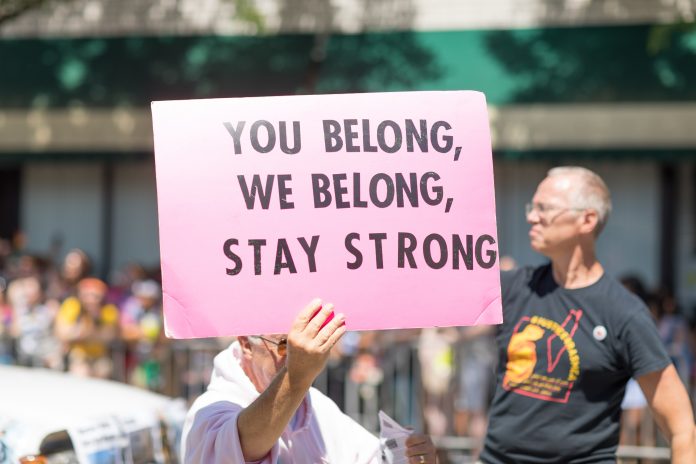

Uniting LGBT voices has always been an integral part of the gay liberation movement, whether in the fight against HIV, the battle for greater economic freedom or simply being listened to.

Social media, dating apps, VPNs and blockchain technology have all played a part in creating these new spaces. They have offered LGBT people more opportunities to connect, explore issues facing their community and most importantly, feel safe.