By Thomas S. Mullaney long Read

I had seen this woman before. Many times now. I was certain of it. But who was she? In a film from 1947, she’s operating an electric Chinese typewriter, the first of its kind, manufactured by IBM. Semi-circled by journalists, and a nervous-looking middle-aged Chinese man—Kao Chung-chin, the engineer who invented the machine—she radiates a smile as she pulls a sheet of paper from the device. Kao is biting his lip, his eyes darting back and forth intently between the crowd and the typist.

As soon as I saw that film, I began to riffle through my files. I’m a professor of Chinese history at Stanford University, and I was years into a book project on the history of modern Chinese information technology—and the Chinese typewriter specifically. By that point, I had amassed a large and still-growing body of source materials, including archival documents, historic photographs, and even antique machines. My office was becoming something of a private museum.

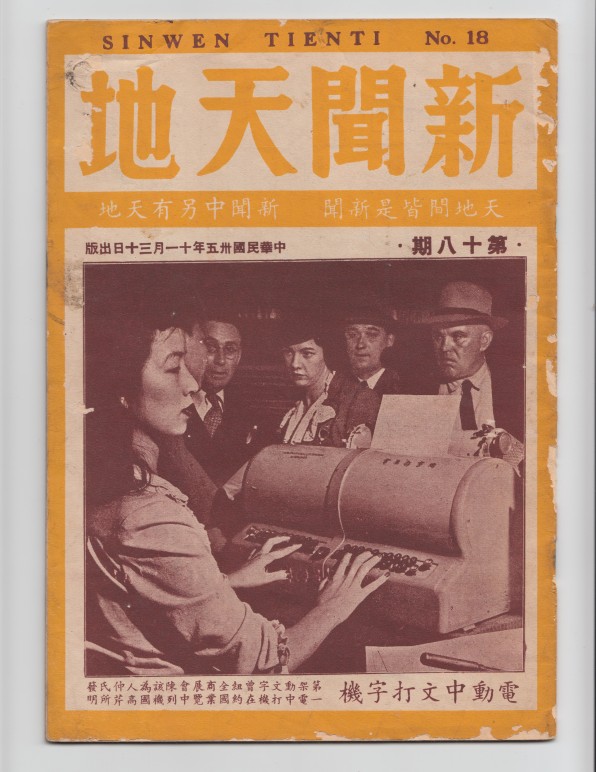

As I thought, I’d encountered the typist previously in my research, in glossy IBM brochures and on the cover of Chinese magazines. Who was she? Why did she appear so frequently, so prominently, in the history of IBM’s effort to electrify the Chinese language?

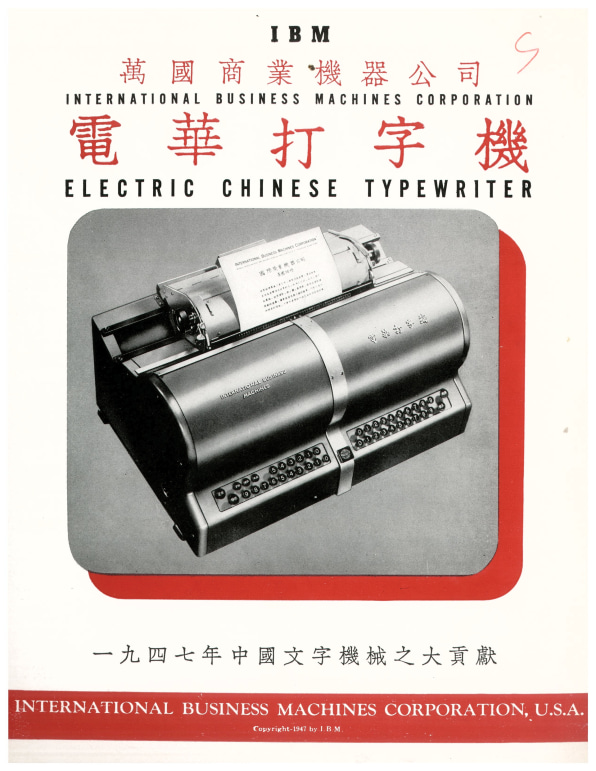

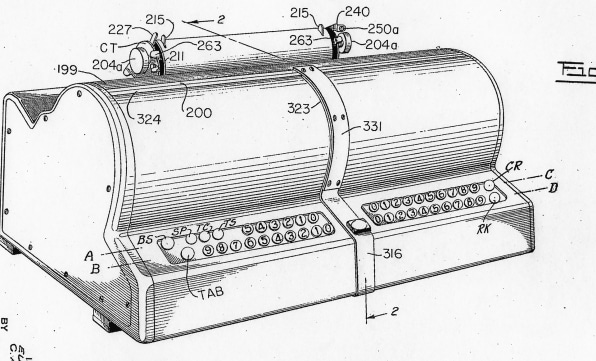

The IBM Chinese typewriter was a formidable machine—not something just anyone could handle with the aplomb of the young typist in the film. On the keyboard affixed to the hulking, gunmetal gray chassis, 36 keys were divided into four banks: 0 through 5; 0 through 9; 0 through 9; and 0 through 9. With just these 36 keys, the machine was capable of producing up to 5,400 Chinese characters in all, wielding a language that was infinitely more difficult to mechanize than English or other Western writing systems.

To type a Chinese character, one depressed a total of 4 keys—one from each bank—more or less simultaneously, compared by one observer to playing a chord on the piano. Just as the film explained, “if you want to type word number 4862 you would press 4-8-6-2 and the machine would type the right character.”

Each four-digit code corresponded with a character etched on a revolving drum inside the typewriter. Spinning continuously at a speed of 60 revolutions per minute, or once per second, the drum measured 7 inches in diameter, and 11 inches in length. Its surface was etched with 5,400 Chinese characters, letters of the English alphabet, punctuation marks, numerals, and a handful of other symbols.

How was the typist in the film able to pull off such a remarkable feat of memory? Certainly, there are a host of professionals who, in the course of their daily work, are able to wield an impressive array of special codes—telegraph operators, emergency responders, court stenographers, trained musicians, police officers, grocery store clerks. But none of them have to memorize thousands of ciphers or codes. This young woman was a virtuoso.

Excited to share the film with others, I posted a brief write-up about it on a blog I used to run, and that was that. One day, however, a comment appeared (a rare occurrence). “Thank You for the memories,” it read. “I am the woman demonstrating the Chinese typewriter in the recent restored movie. If you’d like more info please contact me.”

My heart skipped a beat.

Could this really be her? Or was this some kind of brilliant scam concocted by a netizen with too much time on their hands? I had to respond, but I proceeded with caution:

Dear Ms. Lew,

My name is Tom Mullaney, and I am writing in response to your recent post on my Chinese typewriter blog. I was extremely excited to receive your note, and just wanted to confirm: you are the person who worked with Kao Chung-Chin (Chung-chin Kao) to demonstrate the IBM Chinese Typewriter?

Thank you very much for making contact, and I eagerly await your response,

Tom Mullaney

In the postscript, I included a shibboleth of sorts: a question which, I knew from my research, could only be answered by Ms. Lew herself, someone who knew her personally, or someone who, like me, had spent years in Chinese archives and rare book collections:

p.s. May I ask what your Chinese name is, in Chinese characters?

She responded—accurately.

All of my doubt evaporated, replaced with excitement. I responded immediately, eager to arrange a time to speak. I had so many questions. How did she become involved in the IBM project? What was her background? What was it like to use the machine? How did she manage to memorize all of those four-digit codes? I couldn’t wait for the moment when I could speak to her in person.

But my email to Lew went without a response, first for weeks, and then for months. I sent a polite follow-up email. Silence again. Finally, the trail went entirely cold. I never learned why.

It would be another eight years before I reconnected with Lois Lew, this time thanks to a friend and former employee of hers. Like Lew, he saw a blog entry of mine and reached out. Perhaps because I was vouchsafed, thanks to my exchanges with Lew’s friend; this time the conversation took place. And it was well worth the wait.

“You’ve been looking for me for ten years,” she began, as soon as she answered my call. I could virtually sense her smiling, sending my thoughts back to the 1947 film.

It was true—in fact, it was an understatement. When I first saw Lois Lew, I was 29 years old. On the phone with her, I was 40.

She had traveled a far greater distance. In the IBM promotional film, she was a mere 22. On the phone with me, she was 95.

I couldn’t believe I was finally talking to her.

Lois Lew and the four-digit code

When the IBM Chinese typewriter was debuted to the world, Lois Lew was a worker in Department 76 of Plant 3 of the IBM office in Rochester, New York. Born Lois Eng on December 21, 1924, in Troy, New York, her early life was marked by struggle, political turmoil, and near constant movement. Shortly after she was born, her family returned to China, in the years leading up to the outbreak of war with Japan in 1937. When war erupted, Lew’s family was forced to flee south, largely on foot, on a perilous trek from north China to Hong Kong. Along the way, Lew recalled to me, there were times when she had to carry a sibling on her back.

In Hong Kong, her mother took notice of a family in the neighborhood that struck her as financially stable. Engaging the help of a matchmaker, she inquired as to whether any of the sons in the family were eligible bachelors. She provided a photograph of Lois, and after some time received an answer in the affirmative.

Lois’s mother successfully matched three of her daughters this way, one to a man in Chicago, a second to a man in San Francisco, and a third—Lois—to a man in Rochester, New York. All of these men, her mother was assured, were financially well-off and more than capable of supporting their brides-to-be.

At the age of 16, Lew ventured upon a trans-Pacific voyage by herself, disembarking at San Francisco and then taking a train (again by herself) to Chicago. Her soon-to-be brother-in-law greeted her there and accompanied her to Rochester. She could speak and understand barely a few words of English.

Upon her arrival in Rochester, Lew learned the truth about her new husband-to-be—a man named Yuen Lew—and his financial situation. Far from living a comfortable life, Lew slept in the back room of his laundry shop, along with his sister Gay.

Being too young to marry legally in the state of New York, the couple traveled to New Jersey to form their union. Lois Eng became Lois Lew. And while her new sister-in-law would go on to attend high school, Lois was told that a married woman like her didn’t do that kind of thing.

Lois and Gay were among only a handful of Chinese women in Rochester at the time, a fact which—counterintuitively—may have contributed to their being hired by nearby IBM. “In those days, you didn’t see many Chinese girls,” Lew recounted to me in our conversation. “They would just use us for show: Chinese girls using an American typewriter.” Lew became a capable typist, as did Gay.

Then the IBM Chinese typewriter was unveiled to the world. Suddenly, IBM—and, above all, the typewriter’s inventor, Kao Chung-Chin—needed to find Chinese-speaking typists to help demonstrate the prototype both in the United States and in China. Lois and Gay were summoned to New York to meet with Kao in person.

But then illness struck. Gay contracted tuberculosis, and needed to be hospitalized—and so Lew made this journey, as she had so many in her young life, alone.

Renting a room at a local YWCA, Lew hired a taxi, and was shepherded to IBM’s world headquarters at 590 Madison Avenue. She stepped out of the cab, gazed upward at the 100,000-square foot, 20-story building, and entered the elevator to meet with Kao.

As Kao read over Lew’s resume, which exhibited nothing like an educational background, he was visibly displeased. “Do you know how to spell the word ‘encyclopedia?’” he asked.

Take this chart. Go back to your hotel, and memorize the 4-digit codes for one hundred characters.”

It was a peculiar and even insulting question—a kind of aggressive non sequitur. Lew knew immediately what Kao was after: He was testing her, disappointed in her lack of formal education. But she also knew that Kao’s suspicions were correct: She did not know how to spell this word. Overcome and on the verge of tears, Lew wanted to race back down the elevator, back to the Bronx, back to the YWCA where she was renting a room, and perhaps all the way back to Rochester.

“Do you want me to go home?” she asked.

Kao looked at her, and then looked away. The room fell silent. His decision seemed to take a lifetime. Here Lew was, an IBM plant worker with not even a high school education, who had already failed a basic spelling test in the opening moments of the interview. The question she asked lingered in the room: Do you want me to go home?

What Lew could not have known at the time, however, was that Kao needed her far more than she needed him. Before Lew, there had been another typist—another young woman named Grace Tong who Kao had hired to demonstrate the machine to journalists and executives. Tong was everything Kao had wanted in an assistant. She boasted a college education. Her husband Yanghu Tong was a talented engineer. What is more, she was the daughter-in-law of Hollington Tong, the respected Chinese diplomat and journalist.

But then Kao’s plans were dealt a major blow. For reasons unexplained by the archival record, Tong gave up on the job. One possibility holds that she may have fallen ill, rendering her unable to continue with Kao in the national and international tour of the machine. It is also possible that Tong’s professional life was being steadily consumed by familial expectations (she and her husband were expecting their second child around this time). Whatever the reason, the fact remained: Kao was now in need of a replacement, ideally one with all of the same traits as Tong.

For Kao, Lew was far from the ideal. Even still, she was Kao’s last best chance at winning over incredulous journalists and buyers as to the feasibility of his machine. If the world was to be convinced that his system was tenable—especially the coding system upon which it relied—it would be Lew’s job to convince them.

If she landed the job, that is.

“No,” Kao at last replied, “There’s something else about you.” Kao paused and then sighed. “I have no choice. I have to try you.”

“Take this chart,” Kao instructed her. “Go back to your hotel, and memorize the 4-digit codes for one hundred characters.”

Over the next few days, Kao’s chart was Lew’s whole world. She was on probation, she knew, and everything depended on her ability to memorize this starter set of codes.

The memorization game

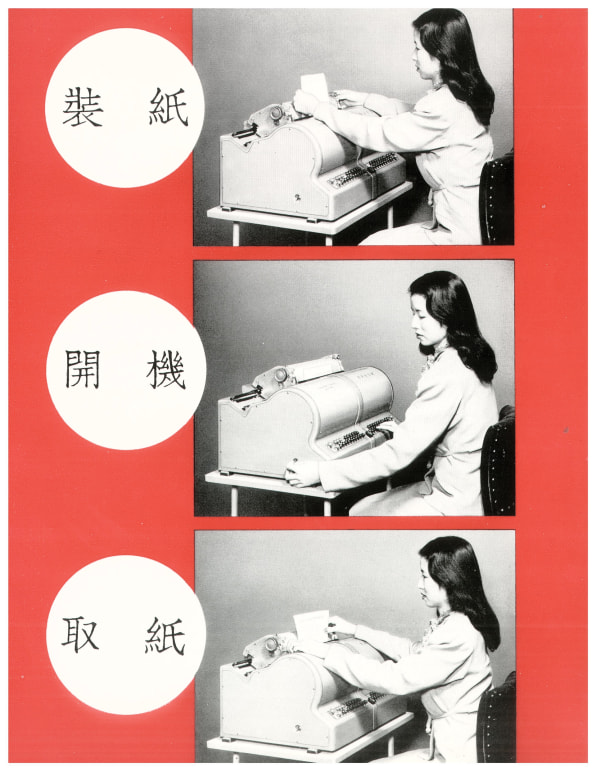

After her first stressful encounter with Kao, Lois spent a week poring over his code book, vying to memorize the four-digit codes for the first probationary set of one hundred characters. She succeeded, and landed the job. And so began an unforeseen journey, one that would take her across the United States and back across the Pacific.

The probationary period gave way to the real training regimen. In the span of three weeks, Lew would need to learn by heart—or, more accurately, by body—the four-digit codes for 1,000 of the most commonly used Chinese characters. Each day, she made the long commute from her furnished room in the Bronx to IBM’s offices.

All of this practice paid off. After completing the training procedure, Lew became Kao Chung-Chin’s main demonstrator for the machine, in shows held across Boston, New York, and San Francisco. The striking young Chinese women made an impression. “My fingernails were red,” she recalls. “I had nylon stockings. They’d never seen anything like that.”

And then came the voyage to China.

The last time Lew traveled by ship across the Pacific, she was a teenager, all by herself, fleeing Hong Kong, and setting out to meet a husband-to-be who she had only seen in photographs. This time, she was a grown woman, flanked by two IBM engineers, and a Chinese inventor. All of her meals were paid for, as was an entirely new wardrobe. She was living like a movie star, as Lew described the experience to me.

To say that Kao Chung-Chin’s hopes were high for the China trip would be a vast understatement. They were stratospheric. As Kao’s son recounted to me, the inventor converted an immense sum of money into Chinese Yuan, the country’s currency at the time—perhaps as much as $250,000, although this figure might be exaggerated. The cash filled up an entire trunk, measuring some 4 feet wide, 2 feet tall, and 2 feet deep. It weighed 250 pounds.

With this immense war chest, Kao would try to secure contracts, establish manufacturing arrangements, and perhaps grease the skids a bit in a country that, as was well known to many, was racked by systemic corruption and graft. Perhaps this was last chance to translate these long and grueling years into something that could make him as famous—in China, at least—as Ottmar Mergenthaler, Thomas Watson, or perhaps even Johannes Gutenberg. His name, his reputation, and a small fortune, were all riding on the trip—and on Lois Lew’s performance.

Even before the team’s arrival in China, the local media had been watching its American demonstrations from afar.

In China, the reception was thrilling. In Shanghai, the mayor of the city was waiting for them at the docks, along with photographers. Lew and the team were treated to sumptuous meals and stayed in one of the nicest hotels in the city. The first of a series of demonstrations took place at IBM China headquarters. The following day, on October 20, 1947, Kao and Lew demonstrated the machine at the Park Hotel in Shanghai, the tallest building in all of Asia. In attendance were scientists, local government officials, and newsmen.

In Nanjing, the reception was even more stirring. The team was met by high-level government officials, and the visit was covered extensively in the Chinese press. Even before the team’s arrival in China, in fact, the local media had been watching its American demonstrations from afar. For months, Chinese outlets had been circulating news of Kao’s demonstrations across the U.S., including those in San Francisco, at Harvard University, and elsewhere.

In preparation for the demonstration in Nanjing, the city had arranged an immense auditorium, and with good reason. An audience of 3,000 people gathered to watch Kao Chung-Chin, the machine, and Lois Lew.

Many would have been overwhelmed by the pressure, but not Lew. She had grown accustomed to the spotlight. New York, Boston, San Francisco, at IBM—all of these experiences had seasoned her, like a veteran Hollywood performer. In front of those 3,000 onlookers and one exquisitely nervous Kao Chung-Chin, Lew was handed one newspaper article after the next, one letter after the next, which she then had to transcribe on the Chinese typewriter.

In other words, Lew had to:

- Translate multiple passages, each containing hundreds of Chinese characters, into their corresponding four-digit codes;

- Perform these translations entirely in her mind;

- Input these codes into the machine (without delay or typo);

- Maintain grace, composure, even a smile, the entire time.

Kao and Lew had prepared for this, however. During the training regimen, Lew was drilled on a variety of letters, in different, common styles. She had memorized all of them.

Coverage of Lew’s and Kao’s demonstrations in China were extensive, and overwhelmingly positive. Stories appeared in Science, Signs of the Times, Municipal Affairs Weekly, Science Pictorial, Science Monthly, and many other outlets. On top of this, publishers were clearly enamored of Lew’s beauty. Her face soon appeared in Zhong-Mei Huabao, IBM promotional brochures, and the 1947 film, among other venues. “I know how to dress,” Lew told me on the phone. “Very sexy looking. I was beautiful.”

The end of the road

For all the excitement over Kao’s invention, as the 1940s drew to a close it became increasingly clear to him that his venture had failed. No matter the success of the Chinese tour, and the American tour before it—and, above all, Lew’s stellar performance throughout—Kao simply could not convince the wider world that his coding system was practical.

American media coverage of Kao’s typewriter did not help his cause. In a July 15, 1946, article in Time magazine, the opening said it all: “The Chinese have a practical reason for believing that one picture is worth a thousand words: it takes so long for them to write the words.” Reporting on Kao’s presentation of the IBM-sponsored machine in at an engineering convention in New York, the article continued:

The machine, which would give a U.S. stenographer the heebie jeebies, has 5,400 characters (the most commonly used of the 80,000 in the Chinese language), mounted on a drum . . . It takes two months for an operator to learn to write simple sentences, four months to achieve the machine’s top speed—45 words a minute (par for a fast typist in English: 120 words).

In the end, however, it was geopolitics that would kill Kao’s project. “The Communist takeover in China was well underway at the time,” a 1964 retrospective article explained, “and was completed before the typewriter had a chance to achieve significant sales in an understandably nervous Chinese market.” Not only did Mao’s victory in mainland China push IBM’s anxieties to the breaking point, it also threw Kao’s national identity into turmoil. He became a man without a country, being issued a special Diplomatic “Red” Visa by the United States. The IBM Chinese Typewriter never made it to market, leaving the challenge of electrifying—and eventually computerizing—the Chinese language to later inventors in the second half of the twentieth-century (a topic I’ve written about elsewhere, including in a forthcoming book on MIT Press called, unsurprisingly enough, The Chinese Computer).

For Lois Lew, life after IBM took her in a completely different direction. She and her husband started a laundromat of their own, and reinvested their earnings, along with earnings from IBM, in the launch of Cathay Pagoda, a new Chinese restaurant in Rochester in 1968. Located just a two-minute walk from the famed, 2,400-seat Eastman Theater, the restaurant attracted, not only a steady stream of students and young people, but also the occasional movie star (Katharine Hepburn among them). The restaurant, which ran for decades, became a mainstay of the city, before its nearly forty-year run came to a close in 2007.

Now in her 90s, Lois Lew swims at the YMCA once a week, three hours each time. She loves to eat, and she remains close friends with former employees from her restaurant. Looking back on her time at IBM, she told me that she has but one regret: “I could have bought IBM stock. Instead, I bought war bonds. Stupid!”

“I still remember the numbers,” she added in passing, referring to the four-digit codes from the Chinese typewriter. She began to rattle them off to me on the telephone. “‘You’, 0-2-7-5. ‘He’, 0-1-7-8. ‘Me’, “0-3-1-4.”

demo, as shown at the Museum of Chinese in America’s exhibit “Radical

Machines: Chinese In The Information Age” in 2019, curated by Tom Mullaney. [Photo: courtesy of Steve Dronzewski]

I couldn’t help but smile. Her vivacity and energy were infectious. After almost two hours of speaking, the time had come to say our goodbyes. I expressed thanks, and we discussed meeting in person in New York City, at a museum exhibit I curated on the history of Chinese information technology—an exhibit in which the 1947 film featuring Lois Lew was to be projected on the wall, larger than life.

I hung up the phone.

As I scrambled to capture in writing the many ideas coursing through my brain, my thoughts turned back to the numbers she had recited to me. Could this be true? Did she really remember the codes seven decades later? Lew had spouted them so quickly during the conversation, without any pause whatsoever, that I felt certain that she was speaking extemporaneously. I dug back through my archival records to track down Kao Chung-Chin’s original list of 4-digit codes.

Looking up the three numbers she had recited, I could hardly believe my eyes.

0275: “You”

0178: “He”

0314: “Me.”

Tom Mullaney is Professor of Chinese History of Stanford University, a Guggenheim fellow, and the Kluge Chair in Technology and Society at the Library of Congress. He is the author or lead editor of six books, most recently The Chinese Typewriter and Your Computer is on Fire (both with MIT Press). His next book, The Chinese Computer—the first comprehensive history of Chinese-language computing—is coming soon.