Education has not dominated national political headlines this midterm cycle and TV ads have focused primarily on inflation, crime, and abortion. Yet education issues have permeated election campaigns up and down the ticket, from congressional candidates to governorships and even school board races, which have seen new influxes of attention and outside spending.

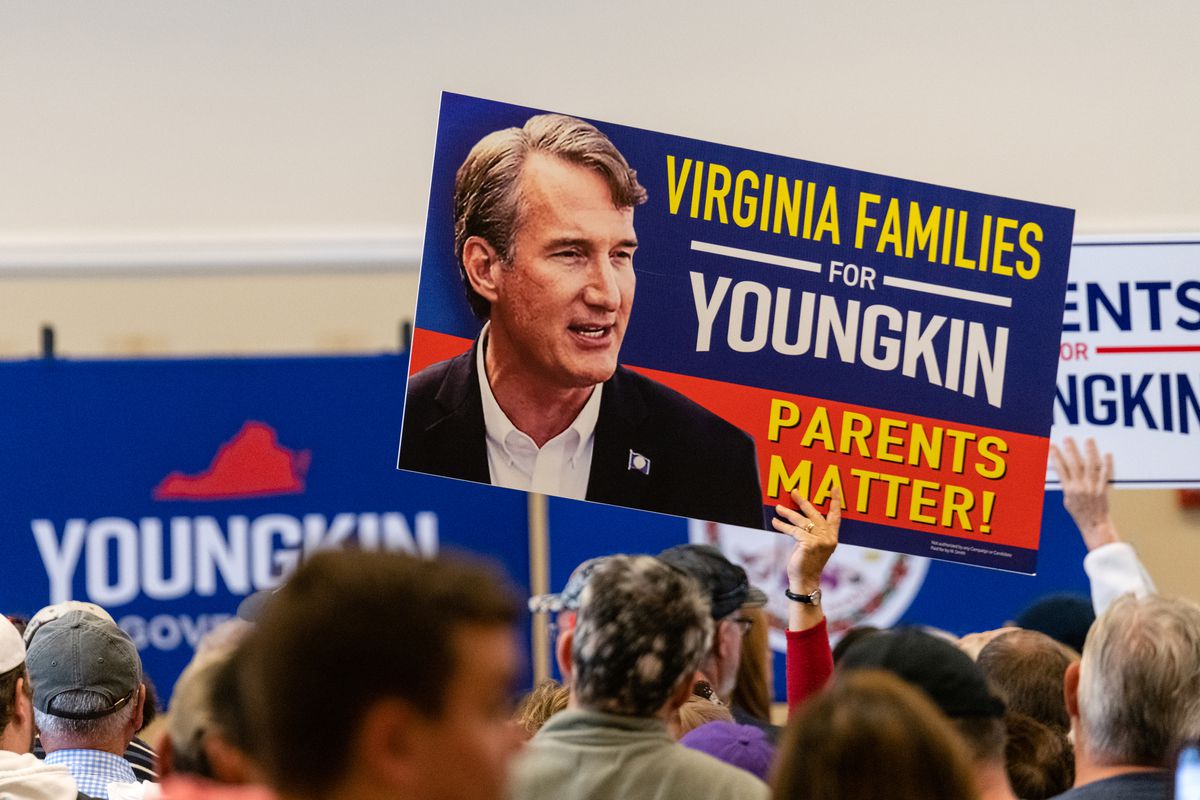

One year ago, analysts across the political spectrum predicted that the national Republican playbook in the midterms would mirror that of Virginia’s newly elected Republican governor, Glenn Youngkin, who won his race after making “critical race theory” and “parents’ rights” central to his bid. After the Virginia election, Democratic pollsters found that 9 percent of Biden voters cast their ballots for Youngkin, with most citing education as a top issue.

The analysts who thought Youngkin’s experience would repeat itself in the 2022 midterms were both right and wrong: Republicans are focusing on winning the same kind of Biden-to-Youngkin suburban moderates who prioritized education and flipped Virginia red. So the education culture wars are at play in this election, but the central issues don’t look the same as they did a year ago.

Critical race theory — a term that, in popular usage on the right, has come to mean nearly any curriculum that refers to systemic or structural racism — hasn’t totally disappeared from the midterms. Most Republican nominees for state education superintendent feature fighting CRT prominently on their campaign websites and more than a half-dozen GOP gubernatorial candidates have said blocking CRT in schools is a top priority for them.

But the issue has significantly faded since the Republican primaries have ended, in part because outside of the Republican base, most voters simply don’t know or care about it, and don’t have a clear opinion on if it should be taught in schools. Even Fox News’s Tucker Carlson has basically stopped talking about the issue, after having mentioned it at least 130 times between May 2020 and November 2021.

But Youngkin’s emphasis on parents’ rights has proven far more potent this year as a rallying cry for candidates — even at the federal level, where House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy has endorsed a “Parents’ Bill of Rights” for schools if the GOP takes control of Congress. Politicians from both parties have sought to appeal to the widely held belief that parents should be more involved in local school matters, including selecting curriculum and opting children out of lessons they may object to.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24166151/GettyImages_1236239044a.jpg)

While Republicans have led on the “parents’ rights” mantra — and have been interweaving their rights rhetoric with plans to promote private school vouchers — even Democrats have been leaning in, including Michigan’s Gov. Gretchen Whitmer who recently formed a new “parents’ council” to advise lawmakers on education policy. Democratic gubernatorial candidates Josh Shapiro and J.B. Pritzker also recently came out to back private school voucher programs, among other entreaties to parents.

While debates around teaching about racism in schools have waned, Republicans have made gender identity and sexual orientation in schools central. Candidates have targeted transgender youth athletes, as well as classroom lessons featuring LGBTQ+ content. Outside groups have been funding TV ads suggesting Democrats endorse sexually explicit literature about same-sex couples for young children, and on the federal level, congressional Republicans have been fanning the flames, rallying behind the Protect Children’s Innocence Act — a bill that would criminalize performing gender-affirming medical procedures on minors. Democrats, for their part, have campaigned affirmatively on protecting LGBTQ+ youth, and increasing funds for school mental health services.

The education culture wars at play in this election also reflect new efforts to capitalize on shifting ideas around which party is more trustworthy on education — a mantle Democrats have enjoyed for decades but appeared to lose ground on following the pandemic. In March 2022, the polling company Rasmussen found 43 percent of likely voters said they trusted Republicans more to deal with education issues, compared with just 36 percent trusting Democrats more. Two more polls conducted this summer by Democratic-aligned groups also found Republicans with a new, narrow edge over Democrats on matters of school trust.

Education, even among parents, almost never ranks as a top voter issue in federal elections, including this year. But it does seem to be ranking as a higher priority in state and local races: a Harris poll from May found parents ranked education as the second most important issue, behind only the economy. More than 4 in 5 respondents to the Harris poll said education had become a more important political issue to them than it was in the past, with 2 in 5 strongly agreeing with the statement.

According to Jeffrey Henig, a political science and education professor at Columbia University’s Teachers College, campaign operatives have recognized that education can be a way to motivate voters who are not traditionally involved in national politics. They may not identify strongly with either the Republican or Democratic Party; they might consider themselves fairly apolitical, “but when it comes to kids, and when it comes to their kids, they respond intensely,” he said. Activating this relatively small swing group has become a major priority to national organizations, who recognize many of the most pivotal races will hinge on small vote margins.

Rebecca Jacobsen, an education policy professor at Michigan State University, emphasized that this is not the first time national groups have shown an interest in local elections for federal education priorities. “I think what’s different now is that the push on the local level is not just being used for pushing an education agenda,” she told Vox. “It’s being pushed because it’s good for overall turnout, for rallying particular groups that you see as important to pursuing your broader political goals, though it is also resulting in a lot of education change.”

How outside groups are targeting typically low-key school board races

School board elections garnered more attention from conservative donors and strategists following the pandemic, who saw opportunities to capitalize on frustrations over masking, remote learning, and school lessons focused on race and gender.

In 2021, the New York-based 1776 Project PAC launched to elect school board members who are committed to opposing critical race theory. The group backed 57 candidates across seven states last year, 41 of whom won. Two former Florida school board members formed another conservative group — Moms for Liberty — in January 2021; they now have over 200 chapters of parent activists organizing around school board races in 38 states.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24166164/GettyImages_1244133447a.jpg)

Armed with a large war chest, the 1776 Project PAC this year has backed school board candidates mostly in Texas and Florida. Founder Ryan Girdusky said they’re funded by over 30,000 small-dollar donors, though they also benefited from a $900,000 donation from the right-wing Restoration PAC.

Additional right-wing entrants into the school board politics scene include conservative groups like the Virginia-based American Principles Project, which focuses on opposing what they call the “transgender agenda” and “hard-line progressive activists” who are “attacking the family.” On top of school board races the American Principles Project has also been funding ads for congressional contests, benefiting from multiple large six-figure donations from Restoration PAC.

School board politics got an unprecedented jolt this past summer when Florida’s Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis came out to endorse 30 school board candidates across several counties that passed local student mask mandates last year. Partisan endorsements aren’t new in school board races, but involvement from the top of the ballot is. “Parental rights, curriculum transparency and classrooms free of woke ideology are all on the ballot this election, and it starts with school board elections,” DeSantis declared — and gave his endorsees cash contributions. (Nineteen of DeSantis’s endorsees were also backed by the 1776 Project PAC.)

The unusual move from the governor prompted a response from his Democratic opponent, Charlie Crist, who then endorsed his own slate of “pro-parent” school board candidates. Most of DeSantis’s endorsed candidates won their primaries, bolstering his influence and position as a potential 2024 presidential contender.

Scrambling to catch up, some education PACs have formed on the progressive side of the aisle. One, called Red, Wine and Blue, formed originally in Ohio in 2019, but last year announced it would expand its focus to states with key US Senate races like Arizona, Georgia, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. Earlier this month the group funded an ad featuring suburban moms in Florida opposing DeSantis’s efforts to ban books, sue teachers, and attack the rights of LGBTQ students.

Another left-leaning group — the Campaign for Our Shared Future — launched this year as a nonpartisan effort, though backed by the New Venture Fund and the Sixteen Thirty Fund, two liberal groups that fund many left-wing advocacy organizations. A job posting for the group said it had raised $6.6 million and was currently fundraising for an additional $6.5 million. The group announced it was spending $300,000 on TV ads in Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Missouri, with ads highlighting book bans, a school board member denigrating transgender students, and an Ohio bill that would have required female school athletes to get genital inspections,

“We were founded to ensure all children have a high-quality and age-appropriate education,” Heather Harding, the group’s executive director, told Vox. “Our work with local school boards is new, but what we’re interested in is ensuring that those who are elected can lead with honesty and integrity and not extremist politicians who are trying to drum up attention for their own gain.”

Republicans are focusing on transgender youth in schools and sports

Republicans at the local, state, and federal level have taken aim at transgender rights this year. At least 160 bills were introduced in 35 state legislatures targeting LGBTQ+ Americans, with most of those bills focused on transgender students’ participation in athletics, parental transparency over what schools teach about gender identity, and parental consent for gender-affirming health care. Republican midterm political advertising has likewise focused on these issues.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24166172/AP22066643429222a.jpg)

DeSantis’s foray into school board endorsements wasn’t entirely driven by whether or not one supported a student mask mandate last year. Florida’s governor also threw his political clout behind conservative candidates who aligned with him on opposing school lessons around gender identity and sexuality orientation.

In March DeSantis signed Florida’s Parental Rights in Education Act — a novel statute that bars teachers from providing lessons on sexual orientation or gender identity between kindergarten through third grade. Liberal opponents of the law branded it the “Don’t Say Gay” law, and Disney, based in Florida, inspired backlash from fans for not standing up against it. But conservative operatives felt confident they were pushing an education position that would resonate with voters, as national polling found broad support among Americans for this type of regulation.

In March, polling firm Rasmussen found that 62 percent of likely voters would support a law like Florida’s parental rights bill in their own state, including 45 percent who “strongly support” the measure. In October, researchers at the University of Southern California released a large national survey finding that most Americans opposed elementary school students learning about gender identity and sexual orientation. While far more Democrats supported teaching young children about LGBTQ+ issues than Republicans, a majority of Democrats also believed these lessons should wait until children were older.

Though Americans repeatedly say they oppose book bans in school libraries and classroom curricula, they’ve also expressed disapproval for specifically assigning students books on gender identity and sexual orientation. Even for high school students, most Americans say they oppose assigning students books on topics that depict experiences of transgender, lesbian, or gay people, and of families with same-sex parents.

This kind of research has emboldened conservatives in other states to introduce copy-cat versions of Florida’s education law, and to fund ads targeting Democrats who seem vulnerable on the issues. One ad funded by the Republican Governors Association in Maine targeted Democratic Gov. Janet Mills, saying her “Education Department was teaching kindergarteners radical transgender policies.” Following the ad, which focused on a LGBTQ+ lesson featured on a state website, Mills had the lesson removed, saying she agreed it was not age-appropriate. In Wisconsin, Democratic Gov. Tony Evers has been attacked for his state education department providing resources on transgender issues for preschoolers.

In Michigan’s gubernatorial election, Republican candidate Tudor Dixon has emphasized that she supports Michigan having its own version of Florida’s Parental Rights in Education law, and has made central to her campaign allegations that Gov. Whitmer has belittled parents’ concerns about books they believe sexualize children. Dixon announced she’d support a statewide ban on “pornographic” books in schools.

Dixon has also been leaning heavily on another related issue that has animated conservatives this cycle: prohibiting transgender girls from participating in women’s sports. In late September Dixon announced a proposal to bar participation in women’s sports to anyone assigned male at birth.

On the federal level, House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy pledged that if Republicans take control of the House they would “defend fairness by ensuring that only women can compete in women’s sports.” The Republican Governors Association has likewise sponsored TV ads around opposition to transgender athletes. Even in congressional races, Republican Sen. Marco Rubio has attacked his Democratic opponent Val Demings in ads for “vot[ing] to allow transgender youth sports and teach children radical gender identity without parental consent.”

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24166233/GettyImages_1235388632a.jpg)

Democrats, for their part, have pledged to protect LGBTQ+ communities, and have been campaigning at LGBTQ+ events. Beto O’Rourke, the Democrat challenging Texas Republican Gov. Greg Abbott, took aim this past spring at his opponent’s positions on gender-affirming health care, and Georgia Democratic gubernatorial candidate Stacey Abrams has spoken up in support of transgender rights.

But Democrats have largely tried to steer away from the specific debates around transgender athletes and direct the education conversation back to school funding. According to a tally by EdWeek, 20 Democratic gubernatorial candidates argue on their websites for increased school funding, and 11 mention supporting student mental health.

Private school vouchers emerge as a wedge issue

As Republicans double down on “parents’ rights,” they are eyeing an opportunity to push their long-standing goals around subsidies for private schools and homeschooling. Most Democrats, meanwhile, are campaigning to keep public funds in public schools.

In some states, Democrats see opposition to vouchers as a key mobilizing plank. Joy Hofmeister, the Democratic gubernatorial candidate in Oklahoma, has been framing her Republican opponent Kevin Stitt’s support for vouchers as a death knell to rural education. (When Stitt ran for the governor’s seat four years ago, he had opposed expanding vouchers himself.) Local reporters have been observing that conservative rural voters seem to be paying attention to Hofmeister’s warnings.

In Arizona, while Republican Gov. Doug Ducey has dramatically expanded private school choice during his eight years in office, Democratic gubernatorial candidate Katie Hobbs has been campaigning on her longstanding opposition to vouchers. In 2018 Arizona voters overwhelmingly rejected a school voucher ballot measure by a 2-to-1 margin, though Republican lawmakers have continued to pass private school choice measures since. Arizona’s Republican gubernatorial candidate Kari Lake has been campaigning on even more robust school choice, like allowing students to take courses at different schools.

Democrats in a few other states see new political opportunity in softening their opposition to vouchers. With less than a month before Election Day, Illinois Gov. J.B. Pritzker announced on a candidate survey that he backed a program that provides subsidies for students to attend private and religious schools. While he didn’t voice strong enthusiasm for it, it’s a change from 2017, when he had blasted the same program.

School choice advocates praised Pritzker for his pivot, noting more than 75 percent of Illinois parents with school-age children back private school choice. Likewise, in September Pennsylvania’s Democratic gubernatorial candidate Josh Shapiro quietly changed his website to add language in favor of private school choice, clarifying later to reporters he is open to giving subsidies to parents to transfer students out of low-performing schools.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24166326/AP22273645459555.jpg)

A year ago there was pundit chatter that voters might turn against teacher unions or elected Democrats who backed school closures during the pandemic. But public opinion for teacher unions hasn’t wavered, and election polls show despite Republican attacks, voters do not seem to be looking to punish officials for virtual instruction.

This is probably in part because many parents themselves were not actually in favor of opening schools quickly before vaccines were available, and parents were largely receiving the kind of instruction they wanted for their children, even as they held concerns about harms of remote leaning. (EdChoice, a national school choice group, polled parents monthly about their comfort level sending their child back to school, and found comfort levels didn’t break 60 percent until April 2021.)

Still, that doesn’t mean the pandemic didn’t foment new trust issues between schools and parents, including around issues like youth masking and Covid-19 vaccines. Some analysts believe the new focus on “parents’ rights” reflects Covid-era frustration that school leaders prioritized culture issues over basic academics and learning loss. Nat Malkus, an education policy expert at the right-leaning American Enterprise Institute, argued in September that Republicans may well struggle to replicate Youngkin’s 2021 playbook, as the critical race theory frustration that Youngkin capitalized on last year resonated because parents were still so exasperated from the pandemic.

But as pandemic-era differences between Democrats and Republicans fade further, and as Republicans identify fewer and fewer examples of actual CRT scandals in schools to keep the alleged crisis alive, Democrats stand a shot at regaining and securing their trust advantage in education. Still, they may not succeed, especially if voters perceive Democrats as opposing measures they find reasonable.

Jacobsen, the education policy professor from Michigan State University, does think the country is at a new inflection point for public education politics.

“A year ago I would have said this is just another case of people saying, ‘Well, everyone else’s schools are failing but I love my school, I love my kids’ teachers,’” she said.

But more recent survey work Jacobsen conducted prompted her to think that many of these narratives around distrust have indeed seeped into parents’ views of their own local schools, too. “We were really surprised,” she told Vox. “There really was a strong relationship between how much you had heard these narratives and the lower levels of trust of your own teachers.”

Jacobsen thinks that it’s too early to say if this marks a lasting change, but that it does reflect a shift from past research findings in the area. “That’s why I’m so worried about these inroads,” she said. “Those who would like to see public education fundamentally changed will have an opening to do so in ways that we have not since [Ronald] Reagan and even before him.”