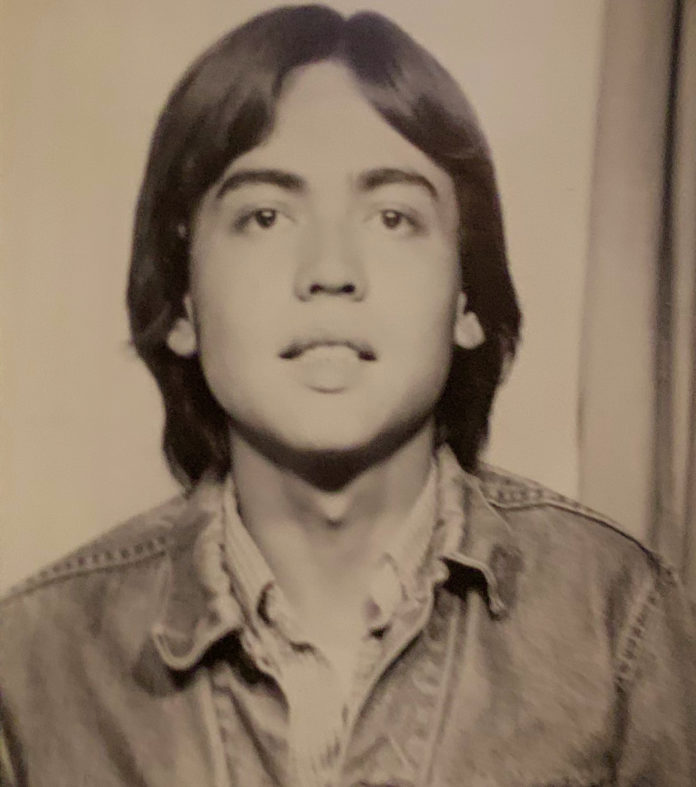

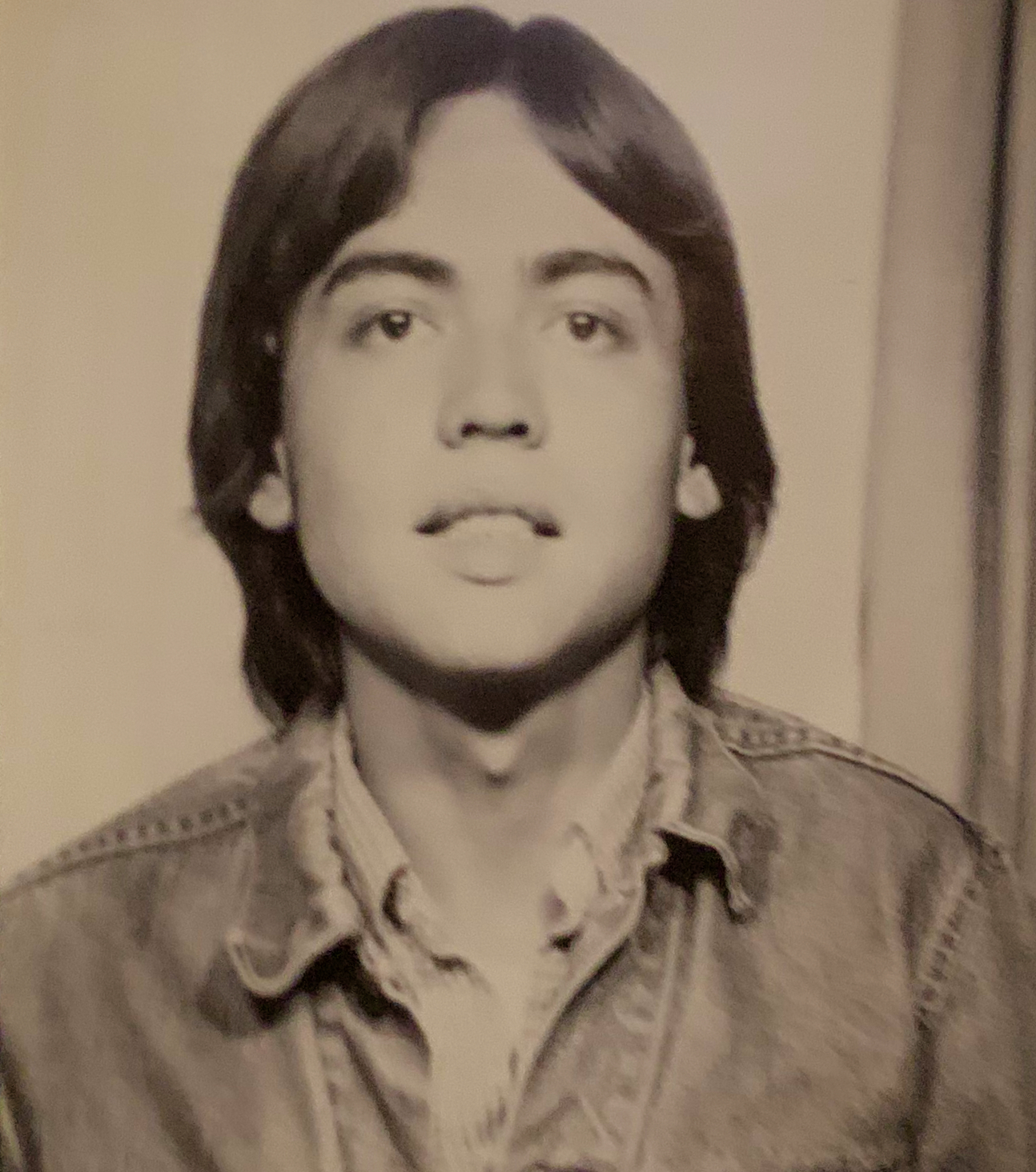

He’d been picked up for truancy before, so he was on the radar of local police. One day, while he was having lunch at a diner, officers strolled in to question him. He landed in juvenile hall and “it snowballed from there.” He said youth corrections officials told him they didn’t want his “homosexuality” to corrupt other kids, so they moved him through a series of youth facilities for nearly five months.

Men in Ampon’s era were often criminalized for being gay. They could be charged with “lewd and lascivious behavior” for simply holding hands, kissing in public or dancing in a bar. Undercover cops who posed as potential sex partners entrapped men in public parks and restrooms. Charges included solicitation, loitering, vagrancy and indecent exposure. Sodomy and oral copulation carried more serious consequences.

But Ampon was a juvenile, so all he had to do to get locked up was skip school and hang around the gay scene. Because back then, a judge could find a teen to be a “psychopathic delinquent” simply for violating social norms. If their parents or guardians agreed, they’d get shipped off to a state facility for an indefinite stay.

With the perspective of time, Ampon can laugh at the label.

“It kind of sounds like you’re little monsters,” he said. “It wasn’t like I’d killed somebody or stole something, but they didn’t really have any idea what to do with gay kids.”

Ampon insisted that his years at Atascadero do not define him. But as a young man, he conceded, “I was angry.” He wrote an account of his confinement after his release that was published by two gay newspapers in the early 1970s. He dedicated his prose poem to “all homosexual prisoners who must daily endure heterosexual justice-oppression.”

In that written account, he described how guards came to his cell with the judge’s order, signed by his parents, too. Soon, he was in handcuffs in the back of a Sheriff’s car, headed to Atascadero.

The car sped south along the California coast

stretching, snapping the ties of family and home.

Sitting, watching his childhood fade thru

the rear-view mirror into mile-long years of fog behind.

Reminding himself to not let them know they’d hurt him;

his defiance shackled to the backseat.

Imprisoned by names he’d been labeled with:

Incorrigable, truant, vagrant, queer, faggot, punk.

“A Menace to Society,” he recalled them saying;

a crime whose only victim was himself.

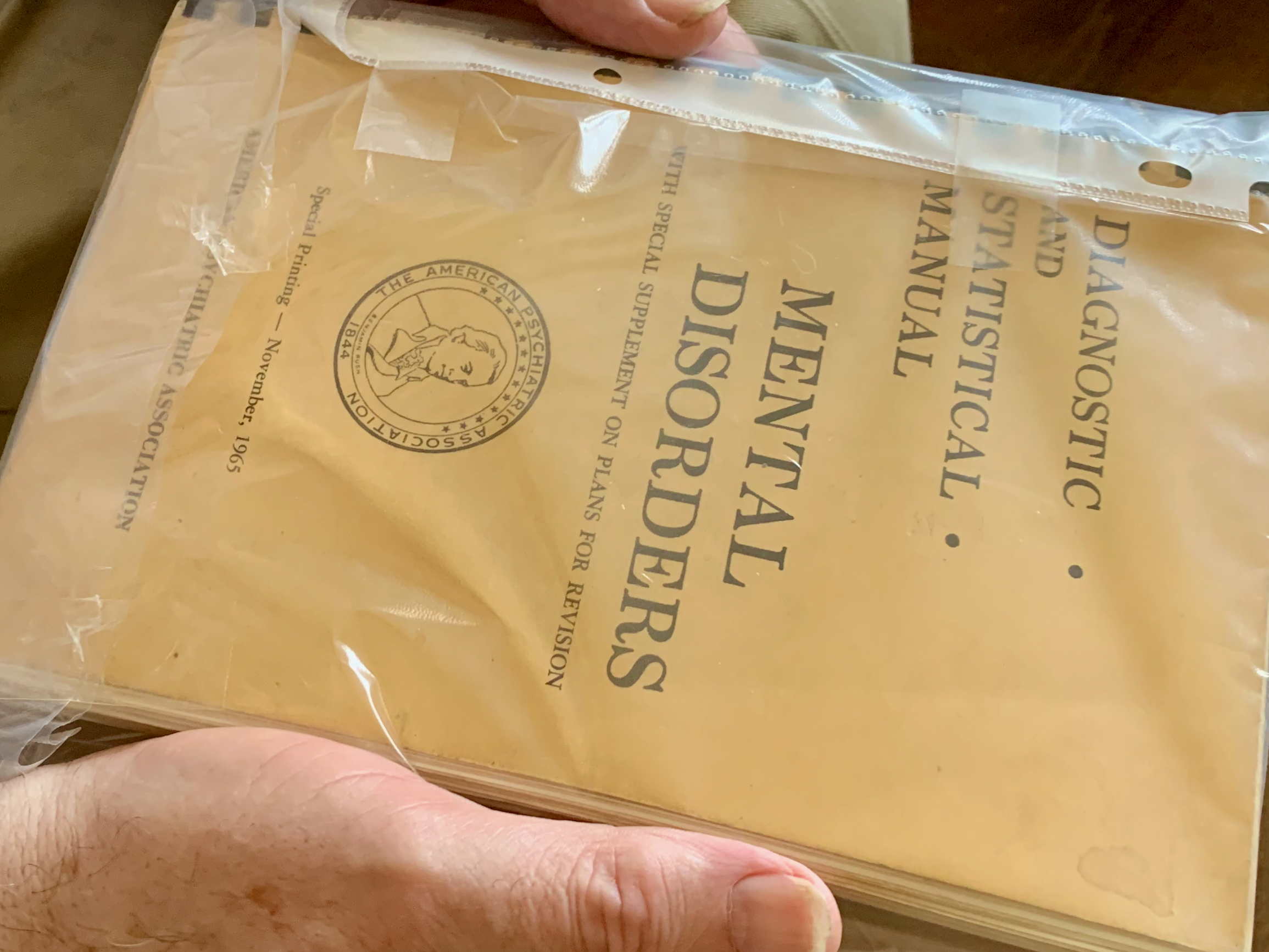

Like everyone committed to Atascadero, Ampon was considered a patient, not a prisoner. He was there for “treatment,” because “homosexuality” was listed in the DSM – the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – since the first edition was published by the American Psychiatric Association (APA) in 1952. Now in its Fifth Edition, clinicians still rely on it in diagnosing mental disorders.

If you were gay in 1962, when Ampon got to the hospital, you’d be diagnosed with “psychopathic personality disorder with pathologic sexuality.”

The teens at Atascadero were in the minority, housed with grown men, some of whom were seriously mentally ill and had committed violent crimes. On Ampon’s second day, a group of adult patients sexually assaulted him.

“It was in the utility room, one of the few rooms that didn’t really have a door,” he said. “It’s where the buckets and mops were.”

To reclaim some power, he converted future assaults into transactions – agreeing to sex in exchange for cigarettes and food.

“I guess I was a growing boy and I always wanted more,” he said, “kind of like Oliver Twist.”

Atascadero would get called out by the radical gay press in the early 1970s for a host of inhumane treatments. One headline picked up nationwide described the facility as a “Dachau for Queers.” A review of historical records indicates that by the time those reports were circulating, the worst was over. But not in Ampon’s day, when there was no radical gay press in existence to call attention to the horrors.

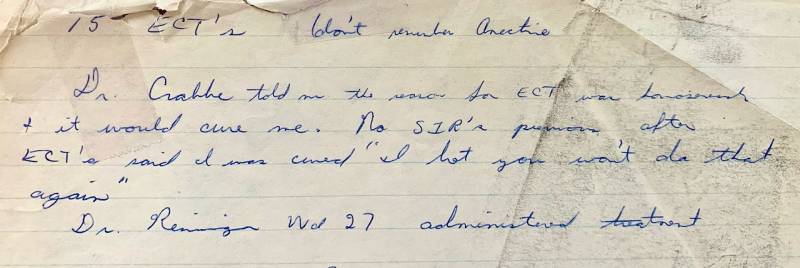

Transorbital lobotomies, performed with an ice pick, occurred largely during the 1950s and were rare by Ampon’s time. But electroconvulsive shock therapy was in full force, for all kinds of patients, not just gay patients. Some received as many as 60 treatments in a single year.

Handwritten notes from an Atascadero research assistant describe one gay patient’s experience. He was given ECT in the late 1960s to “cure” his attraction to men. Then the doctor taunted him, “I bet you won’t do that again.” Ampon knew about these treatments, and wrote about them in his prose poem.

He saw the electric shock box wheeling down the hall

stopping at someone else’s room; the guards taunting

him with the threat, “Your turn next.”

A new terror shot through his thoughts as the overhead light

flickered while each jolt burned into some unfortunate brain.

Ampon’s age spared him the electroshock. Instead, he got a morning dose of phenobarbital for more than two years. Psychiatric medication was relatively new but widely used, often with the sole goal of sedating patients.

Ampon was also punished with solitary confinement, he said. The longest stint stemmed from “a puppy love” crush. When hospital guards noticed the friendship, they shipped his crush off to prison, and Ampon to a sweltering windowless concrete cell, with nothing but a thin sleeping mat. He spent a month there, lost in thought, composing poems about spiders and doom.

Beyond punishment and pills, treatment consisted of pressuring Ampon to not be gay.

“I remember this one doctor who was talking about homosexuality,” Ampon recalled with a mischievous smile. “And he said, well there is a normal homosexual period between 8 and 12 and then beyond that it’s abnormal. So I piped up and said, ‘Is that a.m. or p.m.?’”

His humor is a testament to his resilience, even then. But Ampon wanted out, and he’d end up trying to play the game, telling his treatment team he wanted to “explore” heterosexual experiences “They thought that was good,” he said.

When Gene Ampon turned 18, in mid-1964, he was released. His parents had hardly visited. He was on his own, with no follow-up support. As it happens, he got out just in time. Because “treatment” at Atascadero was about to become even more sadistic.

Read a full-length version of this story at MindSite News, and learn about a few key people who stepped in to fight on behalf of gay men while they were confined at Atascadero and as they were released to the community.

Lee Romney is an independent journalist with a specialty in mental health and criminal justice. Jenny Johnson is a former public defender who co-founded San Francisco’s Behavioral Health Court. This story is a preview of their podcast-in-production, November In My Soul, about mental illness, confinement and liberty in California. Their reporting has received support from a California Humanities California Documentary Project production grant; the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s California Impact Fund; and the California Health Care Foundation. Also, They also thank the research librarians at the ONE Gay & Lesbian Archives at USC, and at the California State Archives.=