A qualitative study among Black gay and bisexual men in Baton Rouge, Louisiana sought to understand how HIV disclosure impacts a person’s life and relationships. The study explored how participants’ intersecting identities and the structural inequities they faced impacted their experiences with HIV disclosure. Men in the study experienced multiple negative consequences from disclosure, including changes to sense of self, strained family and social relationships, and loss of income and housing.

Previous HIV disclosure research has often focused on disclosure as a way to reduce sexual risk and prevent HIV transmission, or disclosure as a way to get social support, thereby improving mental health and health outcomes.

In this study, HIV disclosure was viewed in the framework of biographical disruptions. These are events which interrupt and change a persons’ life story and social relations, such as chronic illness or coming out as gay. Biographical disruptions cause a disturbance to everyday activities, loss of self-esteem, a rethinking of self, and changes to relationships.

Dr Chadwick Campbell of the University of California San Francisco interviewed 30 Black men in Baton Rouge, Louisiana between 2019 and 2020. Eligible participants were men self-identifying as Black or African American, at least 18 years old and living with HIV. Participants were recruited at LGBTQ community discussion groups, by referrals from other men, and on gay dating apps.

Twenty-four participants identified as gay, while the remainder identified as bisexual, fluid, or same gender loving. The average age was 35 (range 18-56) and participants had been living with HIV for an average of ten years (range four months to 33 years). HIV disclosure status ranged from one participant who reported disclosing only to his doctor and one sex partner to three participants who were public with their status, with everyone else somewhere in between.

Most participants (66%) reported some college education, though nearly half made less than $20,000 annually. Half of participants were employed full time, four worked part time, two were self-employed, two were students, and six were unemployed.

Interviews were 60-90 minutes in length and covered childhood and upbringing, family, HIV and/or AIDS diagnosis, HIV disclosure, homophobia, race, and HIV stigma. The interviews asked about previous disruptions in the men’s lives. Nearly all participants (27/29) reported at least one disruption prior to disclosing HIV. Eleven reported childhood sexual abuse, for 14 coming out as gay was a life disruption, and for 19 the HIV/AIDS diagnosis was experienced as a life disruption.

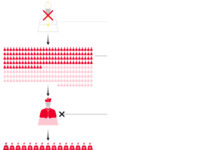

Most men (60%) described life disruptions and negative impacts when others learned about their HIV status. Some men self-disclosed, while others had their HIV status shared without their consent. In either case, the disruptions included a discrediting of self (57%), disrupted family or social relationships (40%), and socioeconomic and structural impacts (27%). Most participants reporting a disruption experienced more than one.

Disruptions to sense of self

Over half of participants described a change in how they viewed themselves due to others learning about their HIV status. One participant, whose mother had told him he was no longer her son when he came out as gay, shared that:

“A lot of people use your information for bad, and really try to harm you… I changed in the world and you never know who your haters are.”

One participant started to feel like he would give HIV to his family:

“They did make me feel like, damn, I’m really going to pass this to y’all. It’s like I’m sitting on a toilet, y’all gotta spray Lysol in y’all cabinet and I’m listening to y’all spraying the seat… even washing my clothes, I had to come back and before y’all put y’all’s clothes in there y’all had to let it run, or Lysol it… So that really made me feel like damn, what if I wouldn’t have told y’all this, and it’s something that I regret because… I don’t know but it just really kind of hurt…”

Disruptions to relationships

Forty per cent of participants had disruptions to family relationships or within their social networks due to others learning about their HIV status. One man disclosed to his mother, who went on to disclose his status to several family members:

“What made me feel like I can’t go talk to my mama and vent to her about anything and tell her something personal is because when I did tell her about me being diagnosed, I did ask her not to tell anybody. And keep it a secret because I didn’t want that being out. And instead of her talking to me about it and letting me know how she felt about it, she went and told one of my cousins, which I don’t trust … So that right there caused me not to be able to tell her personally things like this.”

Another participant disclosed his status to two trusted friends, one of them told someone else, and soon the information spread through his social network. He described that people:

“Didn’t want to talk to me because they heard I had HIV… I felt so… Just ugh… I was talking to somebody… Well, I guess you can say dating… We talked for a little while after my diagnosis… he found out. He said that he couldn’t continue talking to me. Then just all of the weight of the world hit me after… I was like, “All right. I’m out of here.” I don’t know what I want to do, I don’t know what I want to be… See y’all later.”

Socioeconomic impacts

Around a quarter of the men reported that their HIV status being shared had socioeconomic impacts, with several losing housing or their jobs due to their HIV status. One participant saw how accommodating his job was for a colleague with cancer, and he felt he knew and trusted his co-workers. However:

“They handled it horribly, because they didn’t know how to deal with someone who was positive… within the management and the hierarchy they were like, ‘well if it comes out, we don’t want the other employees feeling like they’re not protected, or like we didn’t consider their safety.’ So, them having that fear factor, I think ultimately led me to resign as well because it was a tense atmosphere”.

Another participant’s angry ex-partner printed flyers revealing his personal information and HIV status, which were shared around the neighbourhood. He ended up leaving his apartment and job.

“It’s like everyone at work saw these flyers, everyone in my apartment building saw these flyers and it’s just like, “Whoa.” If I would walk to work and if everyone that’s on the street, now they all know… that destroyed me. Like internally I just felt, no one would ever pretty much want to deal with me.”

Men in the study were particularly vulnerable to negative socioeconomic impacts, owing to their multiple marginal identities at the intersection of race, class, gender, sexuality, HIV status, and geography. One man shared that:

“I don’t feel like I’m accepted with the intersections mind you. If I didn’t have HIV, okay. If it was straight, I would probably be fine. I say that being a black, gay male, living with HIV in Baton Rouge is hard.”

Conclusion

Black gay men living with HIV in the deep south have multiple forces working against them: lower socioeconomic status, racism, homophobia, classism, stigma, and a lack of HIV knowledge in their families and communities. Among this cohort, disclosure of HIV status disrupted the lives of Black gay and bisexual men, who experienced negative impacts to self-esteem, family and social relationships, economic security, and housing status.

The results show that experiences with HIV disclosure are not homogenous nor are they all positive; instead, they are influenced by individual life experiences as well as social and structural factors. HIV disclosure can disrupt a person’s life with serious negative consequences.

Interventions focusing on HIV disclosure should consider these factors and recognise that HIV disclosure is a complex social interaction with lasting consequences. Further, HIV disclosure may do more harm than good, especially among people in high stigma settings or among those with multiple marginalised identities.