The recent photographs from NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope mesmerized millions of Earth-bound mortals, myself included. On display was both the spectacular beauty of deep space and the power and creativity of science.

Shortly after those photos arrived on our timelines did we learn of the uptick in cases of polio in the U.S. On display was an ongoing and by most reports growing skepticism of science.

Framing this dichotomy for me was several weeks in COVID isolation, wondering where my mild to moderate symptoms were going.

Unlike the cold or flu or any respiratory ailment, the coronavirus can play with your mind. A sniffling, sneezing summer cold or a flu bug from hell can make you feel as if you may die. With COVID … well … you know the end of that story. With nearly a million Americans lost to COVID, the deadly degree of separation is small.

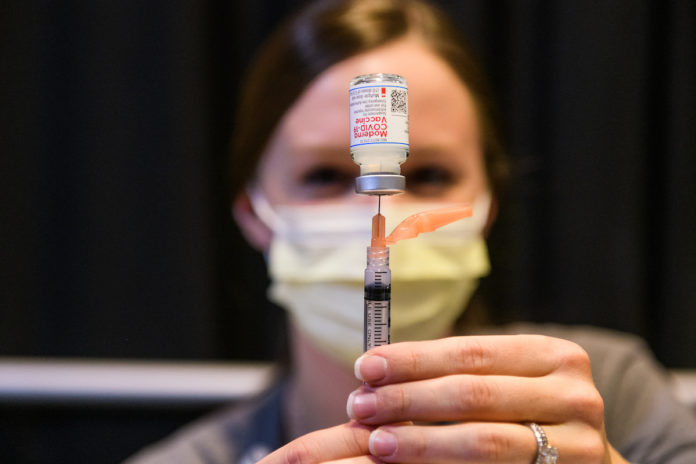

On the other side of COVID, I’m left with a singular feeling: Gratitude … for the healing power of science, because vaccines and boosters and antiviral medication kept me out of the hospital or worse.

Science, now in the crosshairs from Facebook University Ph.D.s in epidemiology and other online experts, has saved me for over seven decades. This newfound repudiation of lifesaving and life-enhancing has, dangerously, diminished the role and importance of science in many American lives, however.

In “The Death of Expertise,” author Tom Nichols addresses this modern take on science and more. “Today, everyone knows everything: with only a quick trip through WebMD or Wikipedia, average citizens believe themselves to be on an equal intellectual footing with doctors and diplomats. All voices, even the most ridiculous, demand to be taken with equal seriousness, and any claim to the contrary is dismissed as elitism.”

My generation was in the vanguard of the polio vaccine, Jonas Salk’s transcendent discovery. Polio cast a giant shadow on our childhoods. In 1952 the U.S. had 60,000 polio cases resulting in 3,000 deaths. Iron lungs were terrifying symbols of lives irretrievably changed. A dear friend, now in his 70s, contracted the deadly disease as an infant and still suffers debilitating pain and disability.

They jabbed us and we escaped the horrors of polio. Science not only made that possible, it altered the arc of history.

We boomers ran the gantlet of childhood diseases: mumps, measles, scarlet fever. The worst of the dismal lot, however, was chicken pox, a painful, disfiguring malady that, unknown to us at the time, would be a lifelong companion. I speak of shingles, as disgusting as its progenitor, but now, too, controlled by a vaccine. I know. Go figure.

Then, vaccines sent us beyond smallpox outbreaks with a scar to prove it; now, millions of parents bet on their children’s future with the HPV vaccine.

Sometimes, the science requires more than a series of shots. We lived in West Hollywood, California, when HIV hit the gay community, panicking all of us … gay or straight. We winced at the telltale signs of friends’ face lesions. We visited them in the hospital, where they were being treated for pneumocystis pneumonia and from which many died. We watched as fear and ignorance put up barriers to solutions. It was heartbreaking.

Still, science knitted together a healing alliance of medicines, therapies and education programs, so that now an HIV diagnosis is no longer an automatic death sentence or even a death sentence at all.

Then came COVID, with its soaring pre-vaccine death rates. Our list of people we knew or knew of personally who died of COVID early in the pandemic exceeded 100 dear souls of all ages, beginning with my first cousin in Idaho … 67, fit and athletic, an avid hiker and family man.

As a society we have weathered, if not conquered, these maladies, but we have much more to do. And, as it has forever, real science using real data and real evidence will lead — whether it’s a vaccine for cancer or a machine that maps our health from birth forward or even foods that reduce or reverse the ravages of disease.

Other epidemics exist: hunger, mental illness, addiction, mass shootings. Can our best and brightest scientists offer solutions? Perhaps, but only if we trust them to search for answers and then trust their conclusions.

Now more than ever we should listen less to science skeptics or social media medics and embrace true science, its practitioners and its extraordinary power to change the world.

This commentary was originally published by the Nebraska Examiner.