New York — “My God what have we done.” Captain Robert A. Lewis, the co-pilot of the B-29 Superfortress called the Enola Gay, wrote those immortal words shortly after 8:16 a.m. on Aug. 6, 1945, moments after he and his crewmates dropped the atomic bomb on the citizens of Hiroshima. The course of history changed at that precise moment: A beautiful day exploded into a blinding bright light, a nuclear fireball leveled a city, at least 100,000 died, and a world war neared its end.

And there, high above it all yet so much a part of the devastation below, was Robert Lewis to chronicle every spectacular and awful moment. He was among the dozen Enola Gay crewmen who delivered the 15-kiloton bomb codenamed “Little Boy” to Japan and the only person aboard who kept a detailed account of the top-secret mission that changed the world.

Lewis’ 11-page chronicle of those few minutes is among the most important documents of the 20th century, a harrowing and oft-heartbreaking account of those very moments between the pre-atomic and post-atomic world — before Hiroshima was struck by the noiseless flash, consumed by fire and swallowed by a mushroom cloud. The public has not seen it since it sold in 2002 during a famous auction of publisher Malcolm Forbes’ American historical documents.

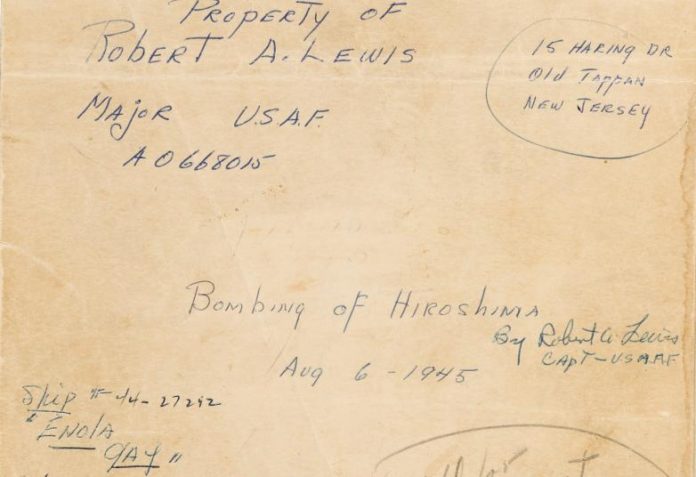

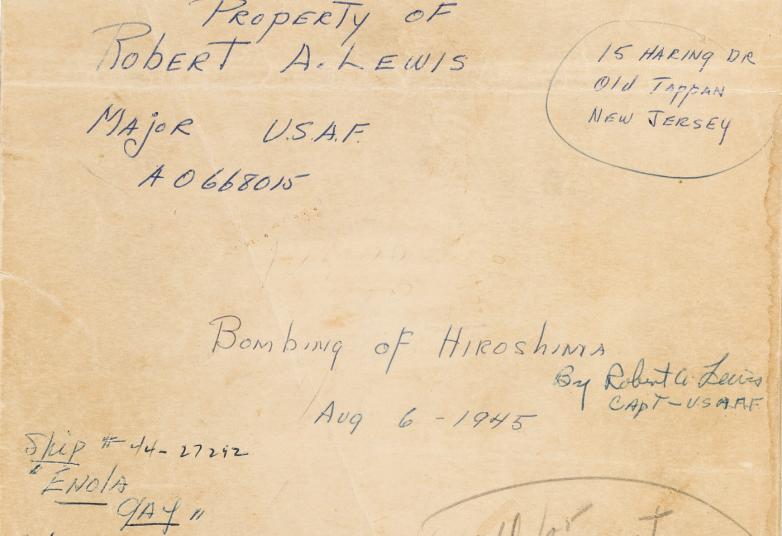

The Enola Gay logbook — its cover bearing among its markings the plain-stated title “Bombing of Hiroshima Aug 6 1945” — resurfaces now at Heritage Auctions as the centerpiece offering in the July 16 Historical Platinum Session Signature® Auction.

This historic auction counts more than 50 of the most extraordinary artifacts offered in Heritage’s history. Lewis’ logbook is being offered alongside autographed manuscripts by Arthur Conan Doyle, Edgar Allen Poe, Mozart and Beethoven; a single leaf from the Gutenberg Bible; the telescope handmade by astronomer Clyde Tombaugh, who discovered Pluto; and the only known signed thermometer scale created by Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit in private hands.

“It is almost unheard of to have a single document marking the dawn of a new age in human history, yet Lewis’ logbook fits that bill,” says Heritage Auctions Executive Vice President Joe Maddalena. “It provides his visceral experience as the only moment-by-moment account of the birth of the Atomic Age. And it will forever stand as a priceless record in the history of humankind.”

The Enola Gay was a particular plane — “an aircraft that could carry a large bomb load higher, farther, and faster than any previous bomber,” per the U.S. government. Fifteen B-29s were modified and assigned to the 509th Composite Group so they could drop atomic bombs. In the end, the Enola Gay was tasked with dropping the first — on Hiroshima if possible; on alternate targets if necessary.

The plane was delivered to the U.S. Army Air Forces in Omaha, Neb., on May 18. It was formally given the moniker the Enola Gay on Aug. 5, after the mother of Col. Paul Tibbets, who chose the plane while it was still on the assembly line and flew it that morning over Japan.

Lewis was tasked with keeping this historical record only when New York Times reporter William L. Laurence could not make the flight. Laurence had been assigned to the Manhattan Project, not by an editor but by General Leslie Groves, who was impressed with Laurence’s ability to foresee the coming of the Atomic Age as early as the fall of 1940. Laurence’s science reporting won him his first Pulitzer Prize; his coverage of the making of the bomb and its use on Japan won him a second. Yet only last year The New York Times noted that “the superstar became not only an apologist for the American military but also a serial defier of journalism’s mores.”

Laurence had been given free rein to cover the creation and delivery of the atomic bomb and expected to accompany the crew of the Enola Gay on August 6. But he was unable to board; history offers myriad reasons why, chief among them the bomb-bearing plane was already too heavy. The reporter asked Lewis to document the flight in his absence. The logbook would forever after serve as history’s guide to the events that transpired in the sky over Japan on Aug. 6, 1945.

Lewis attempted to disguise the top-secret document as a letter to his mom and dad. Its tone vacillates between that of the soldier casually doing his job (“There’ll be a short intermission while we bomb our target”) and the storyteller overcome by what he has witnessed. This is what he wrote between 8:15 and 8:16 that morning, as the bomb seemed to float in the sky just before it exploded over a doctor’s clinic:

“For the next minute no one knew what to expect, the bombardier and the right seat jockey or Pilot [Tibbets] both forgot to put on their dark glasses and therefore witnessed the flash which was terrific,” Lewis wrote. “15 seconds after the flash there were two very distinct slaps on the ship. Then that was all the physical effects we felt. We then turned the ship so we could observe results, and there in front of our eyes was without a doubt !!! the greatest explosion man has ever witnessed.”

He stopped writing what he saw and began documenting how it felt.

“I am certain the entire crew felt this experience was more than anyone [sic] human had ever thought possible. It just seems impossible to comprehend. Just how many did we kill? I honestly have the feeling of groping for words to explain this or I might say My God what have we done. If I live a hundred years I’ll never quite get those few minutes out of my mind…”

A year later, in his book Dawn Over Zero: The Story of the Atomic Bomb, Laurence whittled down Lewis’ logbook narrative to a simple, exclamatory and wholly incomplete “My God!”