Since childhood, Tacoma-born Frank Herbert had been determined to become a published author. For years, he wrote fiction with limited success while working as a journalist. He was hounded by creditors as he struggled alongside his wife Beverly to support a family. But his 1965 science fiction novel Dune, considered by many to be the best science fiction novel ever written, won him the devotion of fans all over the world, launched a franchise that lasted for decades, and earned him millions, which he spent with gusto.

An Enthusiastic Reporter

Frank Patrick Herbert Jr. — he dropped the Jr. — was born in St. Joseph Hospital in Tacoma on October 8, 1920. His paternal grandparents had come west in 1905 to join Burley Colony in Kitsap County, one of many utopian communes springing up in Washington State beginning in the 1890s. The Burley communards printed their own currency, paid everyone an identical salary, and championed gender equality. Eventually, the socialist aspects of the community faded away, and the Herberts ran a general store there.

Herbert’s father, Frank Patrick Herbert Sr., had a varied career including operating a bus line, selling electrical equipment, and serving as a state motorcycle patrolman. His mother, Eileen Marie McCarthy, was from a large Irish family in Wisconsin. According to unsubstantiated family lore, during Prohibition, Frank Senior, Eileen, and another couple built and ran the legendary Spanish Castle Ballroom, a speakeasy and dancehall off of Highway 99 between Seattle and Tacoma.

Herbert’s childhood included camping, hunting, fishing, and digging clams. At 8 he is said to have jumped on a table and shouted, “I wanna be an author.” His parents were binge alcoholics, and young Frank often had to care for his only sibling, Patty Lou, who was 13 years younger. He had a checkered career at Tacoma’s Lincoln High School, including dropped and failed classes. But his career as a writer had already been launched. He was an enthusiastic reporter on the student newspaper. A classmate remembered him rushing into the “news shack” behind the school, shouting: “Stop the presses! I’ve got a scoop!” (Brian Herbert, Dreamer of Dune …).

In May of his senior year, he dropped out. The following summer he worked on the Tacoma Ledger as a copy and office boy, doing some actual reporting as well. In the fall he went back to school, writing feature articles and a regular column for the school paper. At 17, he sold a Western story for $27.50. He was elated, but the next two dozen stories he wrote were all rejected. In 1938, worried about his parents’ drinking and his 5-year-old sister’s safety in the unstable home, he and Patty Lou took a bus to Salem, Oregon, where they sought refuge with an aunt and uncle.

After graduation from Salem High School in 1939, Herbert moved to California and got a job at the Glendale Star as a copy editor. Barely 18, he lied about his age and smoked a briar pipe to seem older. By 1940 the 19-year-old was back with his aunt and uncle in Salem, and talked his way into an “on-call” job with the Oregon Statesman as a photographer, copy editor, feature reporter, and in the advertising department.

In the spring of 1941, he and Flora Parkinson drove three hours north to Tacoma, where they got a night court judge to marry them. Back in California, he worked once more for the Glendale Star, and in February 1942, a few months after Pearl Harbor, he registered for the draft. The next day the couple’s daughter, Penelope Eileen, was born. By July he had enlisted in the Navy and was assigned to Portsmouth, Virginia as a photographer. There, tripping over a tent tie-down, he suffered a head injury that resulted in an honorable discharge. He went back to California, where he discovered his wife and daughter had vanished. His mother-in-law in Oregon wouldn’t tell him where they were. Flora and Frank Herbert were subsequently divorced, and she was given custody of baby Penny.

From 1943 to 1945, Herbert worked as a reporter for the Oregon Journal in Portland. He was writing fiction as well. In 1945 he had his second sale, a suspense story set in Alaska that appeared in Esquire magazine and earned him $200. By August of 1945, he had moved to Seattle and was working on the night desk at the Seattle Post-Intelligencer.

Dreams of a Literary Life

During the day, he attended the University of Washington on the G.I. Bill. There, in a creative writing class, he sat next to 19-year-old Beverly Stuart Forbes. He was immediately taken with her beautiful black hair. The two were the only students in the class who had sold any fiction. In 1946, Herbert sold an adventure yarn to Doc Savage magazine, and Modern Romances bought a class assignment from Forbes. In June 1946, Herbert dropped out of UW and he and Beverly were married in the parlor of a house on Seattle’s Queen Anne Hill, attended by their parents and a handful of other guests. By July, they were honeymooning in the Cascade Mountains at 5,402 feet in an elevated cabin with lots of windows and a view of Mount Rainer. Frank had a $33-a-week job for the Forest Service watching for fires. The couple spent time writing on separate typewriters, and Beverly became pregnant with a son, Brian Patrick Herbert, who was born June 29, 1947, in Seattle.

Frank worked for a number of newspapers around Puget Sound, including The Tacoma Times. He was always able to find newspaper jobs, but the young couple shared a dream of literary success that would allow them to live a rich, full, independent life on their own terms, accountable to no one. After Beverly’s mother gave them a piece of property on Vashon Island in Puget Sound, Frank began building a house there, with help from Beverly. But they ran out of money and the bank repossessed the partially built house as well as the land. Another unfulfilled dream of independence was Herbert’s desire to build his own 45-foot ketch, on which the couple would make a living writing as they sailed around the world.

The family spent years facing economic uncertainty. They moved often without leaving forwarding addresses, trying to elude lawyers representing Herbert’s first wife, Flora, in her attempts to collect past-due child-support payments. Herbert’s son Brian said that during his childhood the family lived in more than 20 different homes.

In 1949 Herbert took a job with the Santa Rosa Press Democrat north of San Francisco. In the Bay Area the couple became close to Jungian psychologists Irene and Ralph Slattery, expanding Frank’s interest in concepts such as ESP, genetic memory, and a collective unconscious. Herbert believed in communication with the dead and that Beverly — who cast horoscopes, read palms, and threw the I Ching — was a white witch who could predict future events and find lost objects.

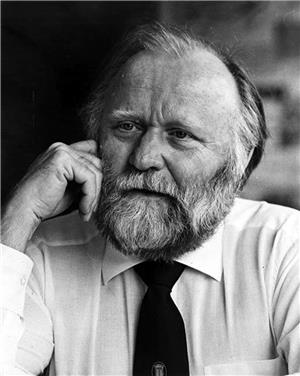

Frank was also drawn to Zen Buddhism, and years later would become a friend of its popularizer in America, Alan Watts. During the clean-cut 1950s, Herbert stood out after he grew a large beard. Brian Herbert described his dad as “a beatnik before they came into vogue” (Dreamer of Dune …). In 1951, a second son, Bruce Calvin was born.

Turning to Science Fiction

Herbert’s first science fiction story, “Looking for Something,” appeared in the April 1952 issue of Startling Stories. That year, Herbert was between day jobs, his first wife had just successfully sued him for back child-support payments, and his former employers had discovered they had co-signed a car loan with Herbert on a vehicle which was now wrecked.

It seemed like a good time to leave town. Successful science fiction and fantasy author Jack Vance suggested the two writers and their families take a trip to Mexico for a while and collaborate on projects. The Herberts borrowed money from Beverly’s relatives and headed south. Herbert later said that while in Mexico, he unwittingly partook of both hashish-laden cookies and morning glory-seed tea. Drug experiences would form the basis for the fictional drug spice melange, a key element in the Dune series still to come. But his writing efforts alongside his friend and mentor Vance didn’t result in any literary sales.

In 1954, the family returned to the Northwest, where Herbert got a job as a speechwriter for Oregon Republican Guy Cordon, who was running for re-election to the U.S. Senate. Herbert was soon spending time in Washington, D.C., and while there he met Senator Joseph McCarthy, a cousin on his mother’s side, at a party. He also visited New York for the first time, where he hired a literary agent. Cordon lost his bid for re-election, but by then Herbert was much more knowledgeable about the federal government, and applied for a government job in American Samoa, which would allow him to write in another exotic locale, as he had in Mexico. When that didn’t work out, the family ended up back in Washington state, in a beach cabin in Healy Palisades, later part of Federal Way.

Beverly picked up work writing ad copy and the family heated the cabin with driftwood gathered from the beach. Frank was now hard at work on a novel set on a submarine. When faced with writers’ block, he took peyote to kick-start his creativity. He later said this was the only time he “knowingly” took psychoactive drugs. Thirty years later, he would be growing chanterelle mushrooms on his property near Port Townsend. Mycologist Paul Stamets visited him there and wrote that Herbert had made a pioneering discovery involving the use of spore slurries to grow mushrooms. Herbert told Stamets that his imagination was stimulated by using mushrooms of the genus Psilocybe while writing.

By the mid-1950s, Flora’s lawyers had found him once again. The IRS was after unpaid taxes, and there were other creditors as well. Frank took on promotional work for the Douglas Fir Plywood Association, and the family moved to the Tacoma Tide Flats. Beverly, who had been working on a mystery novel, put it aside, and got a job writing fundraising copy for Tacoma’s new Mary Bridge Children’s Hospital. She told her husband he could give up his day job and get back to writing fiction full time. Soon, Herbert’s submarine story, “Under Pressure” was serialized in Astounding Science Fiction magazine, and then his agent sold it to Doubleday as a book. It was published as a book in 1956 under the title Dragon of the Sea.

Feeling flush after his first book sale, Herbert bought a 1940 Cadillac hearse for $300, packed up the family and headed south to start a second novel in Mexico. Brian Herbert later wrote that his parents had “naively” run through the advance on the book without paying their debts. When the second novel didn’t sell, they borrowed money from relatives to make it back home.

In 1956, Herbert took a job as a public information officer for a Republican candidate for the U.S. Congress who lost the race. Someone on the campaign told him about a U.S. Department of Agriculture project near the town of Florence on the Oregon Coast. Drifting sand dunes were engulfing houses and threatening the highway. The federal government was planting 300 acres with European sea grass to get the menacing dunes under control.

Herbert was fascinated, and in 1957 he chartered a small airplane to view the scene from above. He began to write a magazine article about the project with the title “They Stopped the Moving Sands.” The article never got off the ground. Herbert felt there was a much bigger story there. He became fascinated by the idea of a planet covered with sand, noting that three major religions — Judaism, Christianity, and Islam — were born in a desert environment. He began reading T. E. Lawrence’s Seven Pillars of Wisdom, and learning about desert warfare and Arab culture.

He was filling file folders full of his research but still had to make a living. In 1958, he visited Tacoma’s Republican headquarters and landed a job on the campaign of William “Big Bill” Bantz, who was taking on Washington’s popular Senator, Henry “Scoop” Jackson in the upcoming election. Jackson won almost 70 percent of the vote.

Beverly was able to provide the family with some stability. In 1959, having written ad copy for the Bon Marché department store in Tacoma, she got a job as advertising manager of a department store in Stockton, California, and the family moved there. The child-support issue was partly addressed by having Penny move in with her father and his family in Stockton. Beverly’s career flourished, and when she landed a job at a department store in San Francisco, the family moved there and Frank took a job at the San Francisco Examiner. In San Francisco, he attended science fiction conventions and socialized with local science fiction writers, although his own literary career had stalled. In the early 1960s, Herbert was making only several hundred dollars a year from his writing.

A Novel of Sand and Worms

But he had been designing the geography, history, ecology, religion, and culture of a desert planet covered with sand and inhabited by terrifying giant worms. Arrakis was short on water, but was the only source in the galaxy of a powerful, highly prized drug. Herbert had so much material that he decided his desert novel would be the first novel of a trilogy. In 1963, his agent sold the first 85,000 words of the saga to Analog magazine to be published in three installments. Herbert was paid $2,295, and began to work on parts two and three.

Eventually, 23 book publishers turned down the two sections of the saga that had already been published in the magazine. Analog, however, said it would publish the rest of the three-part saga that was still unwritten. Herbert got to work and delivered the manuscript in November 1963, resigned to the idea that his trilogy would never be published in book form.

But in 1965, an unlikely book publisher contacted Herbert’s agent, and said he wanted to publish the Dune material that he had read in Analog. The Chilton company was known for its car repair manuals, grease-stained copies of which could be found on garage work benches all over the country. Chilton published the first Analog serial, Dune World, and the second one, Prophet of Dune in hardcover as one novel called Dune. Soon afterward, Ace Books bought the paperback rights.

Herbert kept his day job at the San Francisco Examiner and worked on other fiction projects. By 1969, the second Dune book, Dune Messiah, was published. The books were gaining a word-of-mouth following, especially among college students, and became identified with a new field of interest, ecology.

A Bully at Home

When Herbert got a job at the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, he and Beverly moved back to Seattle with their youngest child, 17-year-old Bruce. Daughter Penny had married a truck driver and started a family in Stockton, and son Brian was living in the San Francisco Bay Area with his wife. Brian, now working in the insurance business, was surprised when his father suggested he and his wife also move to Seattle. As children, the boys had feared their father. He locked them out of the house after school until their mother came home from work so they wouldn’t bother him when he was writing, strapped them up to a Navy surplus lie detector, and hit them with a leather belt after responses he claimed were lies. They suspected him of rigging the machine to falsely register their answers. Daughter Penny got along well with her father, and he never struck her, although when she didn’t finish her dessert, he rubbed it in her hair.

As an adult, Brian forgave his father, saying he grew to love and admire him, and he and his wife did move to Seattle. Father and son became close. Frank Herbert had limited contact with his younger son, Bruce, as an adult. He was unhappy when his son came out as gay, and even more upset when Bruce became a part of queer street theatre in the Bay Area. His father believed Bruce had chosen his sexual orientation, and wanted him to renounce it. Bruce died of AIDS in 1993, cared for at the end by an old college friend in San Rafael, California, with support from the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, a charitable group of gay performers, protesters, and caregivers.

Dune Catches On

The popularity of Dune continued to grow. It was featured in Stewart Brand’s countercultural Whole Earth Catalog, and Apollo astronauts named a crater on the moon Dune in Herbert’s honor. Young people were reading it and rereading it. By 1971, Herbert had quit his final newspaper job. He taught a course called “Utopia/Dystopia” at the University of Washington and wrote other novels before starting another Dune book. They included Soul Catcher, about revenge and culture clash featuring Pacific Northwest Indians; The God-Makers, with a human god created by psychic energy; and Whipping Star, about big government, a particular concern of Herbert’s. Eventually, he would publish more than two dozen novels and many short stories.

In 1972, Frank and Beverly bought a house and farm on six acres near Port Townsend, where he would write the third Dune book, farm, and create some “ecological demonstration projects,” including a tower with a windmill on top of it, a solar-heated swimming pool, and a poultry house heated by methane from bird droppings. They named their new home Xanadu.

In 1976, Children of Dune was a breakout best seller. Herbert got his first book tour, visiting 21 cities in 31 days, including an appearance on the “NBC Today Show.” By 1977, sales of the now completed trilogy had reached 8 million copies. The movie rights to Dune had been sold to a French film consortium. Producer Alejandro Jodorowsky had planned a film with a 12-hour running time, gone through $2 million, and was feuding with one of the actors, Salvador Dali. Other cast members included Orson Welles, Mick Jagger, and Gloria Swanson. The project collapsed. Italian producer Dino De Laurentiis bought the rights and hired Herbert to serve as technical advisor. Herbert bought a sailboat with part of the advance. Director David Lynch was hired to write a PG script that ran no more than 2 hours, 15 minutes.

A search was on to cast the hero, Paul Altreides, with an unknown actor. They discovered a young University of Washington theatre graduate and Dune fan, Kyle MacLachlan, who was playing in Tartuffe at Seattle’s Empty Space Theatre. As part of the publicity buildup, the actor would not be revealed until the film’s debut. MacLachlan was shot with his back to the camera in promotional interviews.

Lynch began shooting in Mexico. Dune eventually ran 5 hours long and had 39 or 40 speaking parts, including roles for Max Von Sydow, José Ferrer, and Sting, as well as 20,00 extras. Inspired by the success of Star Wars merchandise, Paul Atreides dolls, toy sandworms, a World of Dune teaching kit, coloring books, board games, Dune weapons, calendars, and more were prepared.

In 1980, Beverly had been diagnosed with lung cancer, was increasingly frail, and wanted to spend time in a warmer climate. The Herberts bought property in Hawaii and hired an architect to design a home with a pool, solar panels, a windmill, and a caretaker’s house. In 1981, after the success of an unplanned fourth book in the series, God Emperor of Dune, Herbert received what was said to be the biggest contract ever for a science fiction novel, for a fifth Dune book. He also expected to earn millions from the film, and wanted to spend a few of them setting up a foundation for a “study of social systems.” Herbert was concerned about governmental overreach and had come up with a system in which citizens could overturn decisions made by bureaucrats, and the U.S. House and Senate would be eliminated.

Beverly Herbert died in February 1984. In April, Herbert, now 63, went on tour to promote Heretics of Dune, the fifth in the series, and later told his son that he had fallen in love with Theresa Shackleford, a 27-year-old Los Angeles publicist who worked for his publisher, Putnam.

On the plane from Los Angeles back to Seattle, Herbert believed he was picking up data from Theresa’s brain as she thought of him. Simultaneously, he had “received a message” from his dead wife: “It’s all right. She’s the one. You’re still alive Frank! Live your life!” (Dreamer of Dune …). There were two other women whom he also saw as romantic prospects, both in their forties. For a time, he was trying to decide among the three. The two fortyish candidates were clearly interested but he felt that while Shackleford liked him, she wasn’t attracted to him. But soon, he and Shackleford were taking skin-diving lessons together in Los Angeles. In December, Herbert and Shackleford attended the world premiere of the Dune movie at the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, D.C., followed by a state dinner at the White House. President Ronald Reagan and his wife Nancy told him they liked the movie.

But the critics didn’t. After blistering reviews, further press screenings were canceled. The movie had been cut from five hours to a little more than two hours, which had affected the narrative badly. It was called “incomprehensible,” “confusing,” and “a total mess.” The New York Times said, “[s]everal of the characters in Dune are psychic, which puts them in the unique position of being able to understand what goes on in the movie” (Maslin). Herbert said, “they cut the hell out of it” (Dreamer of Dune …). He was expecting a percentage of the hefty profits. But there apparently weren’t any. Dune earned $30 million in the U.S. market but had cost $40 million to make.

Final Chapters

After Beverly’s death, son Brian, who had left his job in insurance to work for his father, performed some of the bookkeeping tasks she had once performed. He discovered his father had accumulated a lot of debt, including to the IRS. Undaunted, Frank Herbert was planning more improvements on the Hawaii property, including an apartment for a maid or gardener, blue Italian tile installed in the gazebo by the pool, a waterfall, and a carp pond. He was working on a design for a new house at Xanadu for Penny and her husband, who were caretakers there. Herbert’s plans also included a trek in Nepal with his friend Jim Whittaker, the first American to climb Mount Everest, and a subsequent trip to Tibet to become the oldest man to reach the summit of Everest.

In 1985, the sixth Dune book, Chapterhouse: Dune was an immediate best seller around the world. And, Theresa Shackleford married Frank Herbert in Reno, Nevada, on May 18, 1985. By November, he was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer and received experimental treatments at the University of Wisconsin. He returned there in January 1986 for more treatment but died unexpectedly from a pulmonary embolism. He was 65 years old.

He left behind a saga that had touched the lives of many fans. People who like Dune really like Dune. Superfan Stephen Colbert read it at 19 and re-read it more than 35 years later. His enthusiasm hadn’t waned, and he called it a “coming of age story not just for Paul Atreides but for all humanity” (“Dune Cast Interview”).

After Herbert’s death, his son Brian and co-author, Kevin J. Anderson received a $3 million contract to write three more Dune novels. They wrote a seventh Dune book in the original series, followed by multiple prequels and sequels. A new movie version of the first Dune novel was scheduled for theatrical release on October 1, 2021.