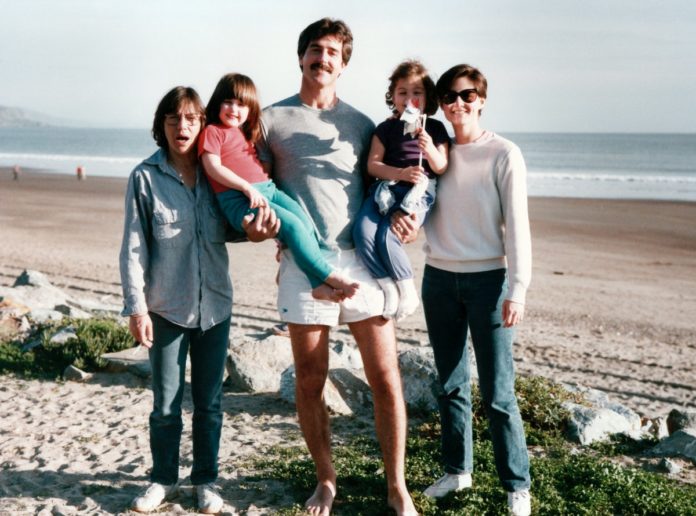

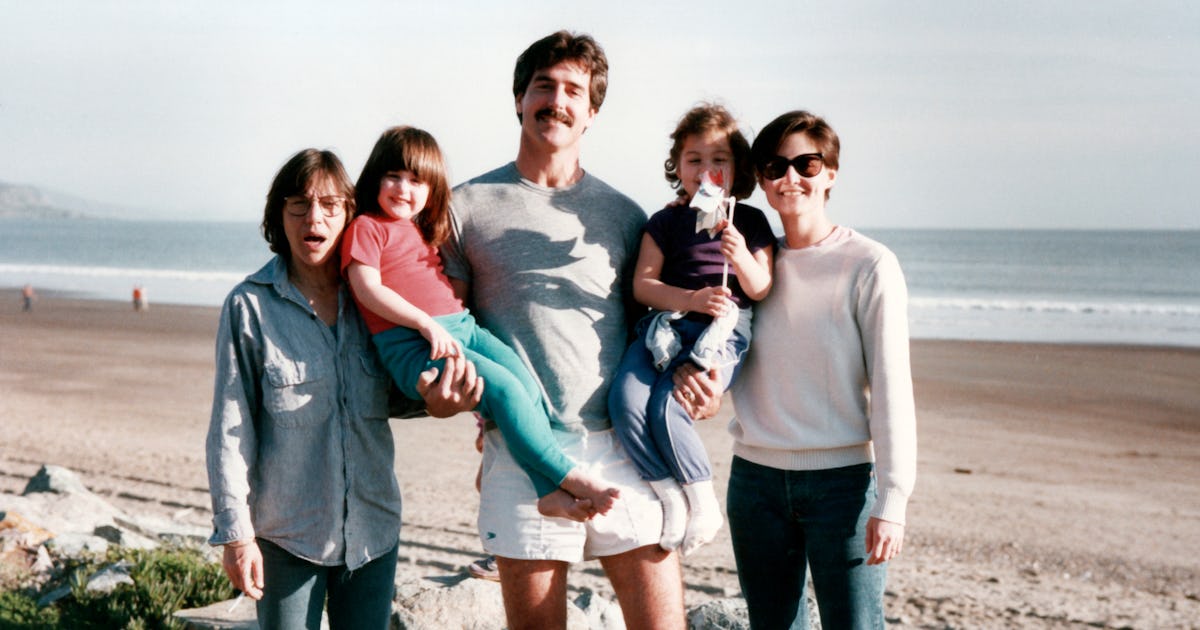

In the opening sequence of the docuseries Nuclear Family, filmmaker Ry Russo-Young arranges her parents in front of the camera for an interview. “Are you guys comfortable?” she asks. Ry, age 16 at the time of this early footage, giggles as Robin Young, her mother, beams and gazes directly into the camera. In contrast, Sandy Russo, also Ry’s mother, looks decidedly wary.

“Briefly describe your names and, of course, your relationship to Ry,” Ry directs.

Russo bristles. “Is this all going to be in the third person or something?” she asks. Her impatience is palpable.

“It depends — it’s really up to you,” Ry answers.

Several beats pass.

“Well, I’m Sandy Russo and I’m” — she raises her eyebrows — “your mom.”

It’s a moment of private tension made public, a tension that becomes increasingly understandable as the film progresses and we learn that Russo’s parenthood was legally challenged when Ry’s donor, a family friend at the time, sued for custody.

Nuclear Family blends extensive interviews with archival clips and footage from home movies that span decades. This mix allows us to see the conflict between parents and donor unfold from multiple perspectives. Because Russo-Young herself is either behind or in front of the camera in every scene, we never lose the thread of tension that propels the film. What emerges is a cautionary tale without a simple moral, a compassionate portrait of humans driven by a need for both connection and control.

As a lesbian mother myself, I was riveted by Russo-Young’s willingness to unpack the complexities of parental and donor connections. We chatted recently about telling personal stories, hard conversations, and listening with no agenda.

You make it clear in the film that you’ve made multiple attempts to tell this story, so I’m wondering: Why now?

The personal reason is that becoming a parent myself really changed me. I realized the stakes of what it is to be responsible for another person, to love them relentlessly. The notion of having that child be taken away from me or not being able to control what happens to that child was visceral to me in a way that it never had been before.

In addition to all the personal layers, I would often wonder is the culture ready for it? I didn’t want the homophobic questions of yore to dominate the conversation. And I also didn’t want to make this film before the culture was ready for a more complicated and nuanced portrait of gay families. So, I think now there is more space for a story that is complicated and multifaceted.

I also didn’t want to make this film before the culture was ready for a more complicated and nuanced portrait of gay families.

One question that seems to be a point of tension in the film is: How important is the biological connection between donor and child? What’s a donor’s role and how much access should they have to the children they help conceive? I know from my own research that people have wildly different views on that. What are your thoughts?

Well, most importantly, I see my family as my moms, my sister, and me. My moms are my parents. Tom [Russo-Young’s donor] was never a parent. But I think the question of his placement in my heart and in my life has been something that has always been unsettling to me and not resolved. So, in a way, yes, the movie is about finding what place he has, but I never saw him as a parent. And I think that families are families that include biology or don’t include biology. I don’t think families are defined by biology. They can be, but they certainly don’t have to be.

Do you think that the conflict that led to that lawsuit, the tension between your parents and your donor, came about because we just haven’t had time as a culture to clearly define the donor’s role?

Absolutely. At that time there was no roadmap for that relationship, but most importantly, there were no protections for my mothers. So, I think my moms were living in fear, even at the dawn of the conflict, because they knew that they weren’t protected by the law. And I think the lack of protections affected the relationship on all sides.

At that time there was no roadmap for that relationship, but most importantly, there were no protections for my mothers.

I think if this had happened today, it probably wouldn’t have been as ugly because everyone would’ve felt secure and safe in their roles. Because the family would have been defined from the very beginning as a nuclear family. And then he could have a more liberal role.

I don’t worry about my nanny taking away my child because I know that my child is my child. But if I didn’t, I would be reluctant to let her get so close to him.

I appreciated the tension you so succinctly framed in the film between these ideals of the expansive queer family versus the insular nuclear family structure.

Yeah. Russo and Robin were clear from the beginning that they wanted a nuclear family, and that’s what they set out to create. In the film, and at the time, because gay families were so undefined within our culture, there was this question of “What does a gay family look like?” Does it look like the community raising the child? Does a child with gay parents have four parents?

I was wondering about the tension that’s so palpable in the film. Much of the film is made up of conversations with people who had been part of or adjacent to this family conflict and who hadn’t spoken about it in years. It’s clear that the stakes are high and everyone has emphatic opinions. How did you navigate that?

I tried in the very beginning to take the ethos that my moms had always given me, which is to be completely transparent and honest with everyone I talk to. But I also had no agenda in going in to make the movie, other than to hear what everybody had to say. So, when I went and talked, approached Chris Arguedas [a longtime friend who was cut off from the family during the lawsuit], for example, I had to make it clear that I came with no agenda. And what was surprising to me is that she said, “I’ve been waiting for you for 30 years to come and talk to me,” and she spoke for three hours, which as a filmmaker, was really exciting.

One of the things we do in traditional narratives is we create heroes and villains because it’s clear and easy to swallow. I always felt that that was a little simplistic.

Those difficult conversations were very much a part of why I wanted to make a documentary. I had a sense that I would go through something as a result of hearing the other side of the story.

One of the things we do in traditional narratives is we create heroes and villains because it’s clear and easy to swallow. I always felt that that was a little simplistic. And so, I think in approaching this I tried to really understand everybody’s motivation and to portray a more layered and complicated version of the story.

Did you have to do anything particular to make space for your own feelings and self-care during that time?

Well, I was taking care of a baby. I had my second child in February 2020. We shot the interviews that you see during the pandemic while I had an infant. So “my space” was that pure time with my children, where there can be nothing else other than taking care of the little life right in front of you. And that was both stressful and magical at the same time.

I noticed that in the first two segments of the series, we mostly see footage of you at 16, rather than your present-day self. Then your present-day self plays a big role in the final segment. Can you tell us about your decision-making process there?

I wanted the viewer to go on the journey with me, in terms of how I experienced this whole story. I wanted the film to mirror my psychological arc. So, in the beginning, I’m a blood cell, I’m a baby. I don’t belong as a strong voice in that first episode because I didn’t have a strong voice. I wanted the viewer to experience that first episode how I experienced it, which is more like a fable, and a story that my mothers have been telling me my whole life.

The second part, at 16, I was closer to what I thought at 9, so that’s why we used that interview. Basically, I wanted the entire series to track my psychological development. And I didn’t really understand how I felt until I was older. I mean, I totally had a perspective at 16, but I didn’t want the audience ahead of me. I wanted them to understand that in the second part, I hated him [Russo-Young’s donor] and I felt he was evil. And that’s how I felt when I was 16, so we used that.

I wanted the viewer to experience that first episode how I experienced it, which is more like a fable, and a story that my mothers have been telling me my whole life.

Can you tell me where that early footage came from? Had you tried to make a documentary at 16?

No, let me explain. In 1999, when I was 16, my family participated in a documentary called Our House by filmmaker Meema Spadola. It followed five LGBTQ families, and my family was one of them. I’ve since become friends with the filmmaker, and she was kind enough to give us the footage, including the raw footage. So, the pieces of the footage that had made it in her cut, I was very familiar and comfortable with. But seeing other clips from the raw footage and from other press that I had forgotten about was sometimes shocking to me. For instance, the moment when I say on Leeza that I had only seen my sperm donor once or twice before. That was shocking to me. I had forgotten that I had said that.

That was a striking moment in the film.

It was striking to me, too.

I feel like the tiny glimpses we get of the present-day you before that third segment — they’re powerful. They’re enough that we know you exist.

Well, that’s all we needed. And the truth is that my moms are fantastic subjects. They’re incredible storytellers. They’re charismatic. Chris [Arguedas] is too. These are people that have strong conviction and are fascinating to watch. And so, I didn’t want to gunk it up with me.

What do you hope audiences will take away from the film?

While I do think this story is specific to gay families and gay culture, I also think the film taps into more universal themes of family, and love, and loyalty, and loss, and that the series invites viewers to think about their own families and how fraught those relationships are. And that was really my hope in telling this story, to have viewers reflect on their lives. That’s the purpose of personal art to me.

The first episode of Nuclear Family is available to stream on HBOMax