Laurel Wilson is a historian and genealogist with a focus on African American heritage in Decatur and DeKalb County. She holds a master’s degree in Public History from Georgia State University and has practiced genealogy for over 20 years. You can learn more about her work and contact her via Decaturhistory.com.

Editor’s note: Decaturish asked Wilson to write this article after the Junior League of DeKalb County announced plans to rename the Mary Gay House. For more information about that, click here.

By Laurel Wilson, contributor

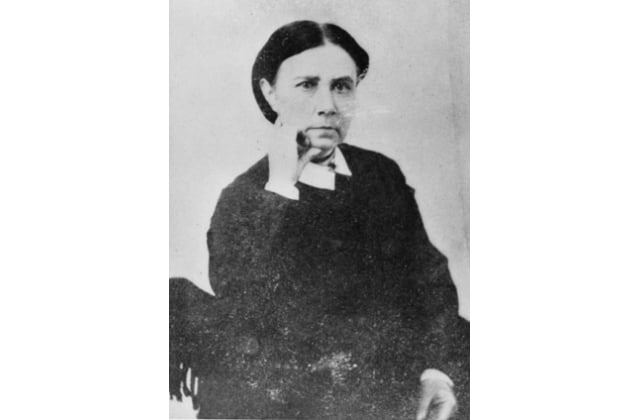

In the years I have spent researching Black history and heritage in Decatur and surrounding DeKalb County, it has been an unfortunate necessity that I study Mary Gay because her book “Life in Dixie During the War,” along with historical documents about her family, has helped me identify and name some of the enslaved people of Decatur. Mary Ann Harris Gay has long been a historic celebrity, and even a hero, in this community, praised for her determination and pluck and her generosity to those in need. Indeed, it is even true that she was the inspiration and model for Scarlet O’Hara. And like Scarlet O’Hara, much of her struggle was due to her own arrogance. Because of her vehement support of white supremacy, Gay lost her ill-gotten fortune, an inheritance that was built upon theft, murder, and slavery.

As we approach the year 2023, it is abundantly clear that the Civil War was fought over slavery and more specifically white supremacy. Alexander Stephens, The Vice President of the confederacy himself, spelled this out in what is now known as his Cornerstone Speech, which was given just three weeks before the attack on Fort Sumter.

Mary Gay and her family invested nearly all their family fortune into Confederate war bonds, so confident were they in the ultimate success of white supremacy. After the War, Mary Gay was incredibly active in preserving the legacy of The Lost Cause. She was a charter member of Decatur’s Agnes Lee Chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy and the namesake of Decatur’s Mary Gay chapter of The Children of the Confederacy. She was well-recognized as a fundraiser for the Alexander Stephens memorial in Crawfordville, Ga. and raised money to build a Confederate cemetery in Tennessee, where her brother was reburied. She has been praised for her book, “Life in Dixie During the War,” which she is said to have sold door to door to modestly support her impoverished family after the war. In reality, “Life in Dixie” was a work of white supremacist propaganda, and its profits were used, at least in part, to fund Confederate memorials. As for the quality of her writing, it is worth noting that Mark Twain enshrined his mockery of her poetry in Tom Sawyer, much to Miss Gay’s bitterness.

Despite Mary Gay’s pearl-clutching over the presence of the monstrous Yanks in Decatur, she was not, in fact, mistreated. Though some of her livestock was taken to support the troops, unlike the fates of untold other homes in Sherman’s path, Mary Gay’s house and property were left standing, with no harm coming to anyone in the household. In fact, she was respectfully addressed by military leaders, and the troops who briefly occupied her property provided her family and those she continued to enslave with food and medical supplies. Furthermore, she was also able to move about freely across the state during the war. In fact, Miss Mary boasts a great deal about her treasonous acts during the Civil War, including but not limited to manufacturing, concealing, and relaying supplies to Confederate troops and even spying.

Mary Gay was an educated woman who knew well the true nature of slavery and who faithfully upheld the Confederate virtues of white supremacy. In 1892, when she wrote in “Life in Dixie” that the “menial race” received “more than any other people in bondage has ever received…good wholesome food, comfortable homes and raiment, and tender treatment in sickness,” this well-read woman quite likely would have been aware of another book, “Slave Life in Georgia,” which was published in 1855 and was written by John Brown, a man who escaped enslavement from her very own family. Entire chapters of “Slave Life” are dedicated to the brutality and sadism of Mary Gay’s grandfather Thomas Stevens and her uncle Decatur Stevens. But even if she had not read this book, having been raised closely since young girlhood in and around the plantations of these men, she would have been witness to or have heard rumors of the gross conditions and treatment of the Black men, women, and children under the paternalistic “care” of her family.

As Mary Gay’s fortune and heritage were created by her grandfather, and because in her youth she lived with him, it is important to at least briefly explore the foundations of the family’s success. Thomas Stevens was a farmer and whiskey distiller who owned property in Twiggs, Baldwin, Cass (now Bartow), and DeKalb Counties. Appearing in records as early as 1827, Stevens was among the earliest white settlers of DeKalb County.

In one of the counties where he owned land, after participating in a plot to steal land from a man named Morgan, who was disliked by other farmers because he preferred to pay his laborers, both Black and white, Thomas Stevens himself murdered Morgan on the road for attempting to steal corn for his family after financial ruin. This crime was never punished as the only witness was John Brown, whose testimony was not allowed in court as he was merely chattel.

By 1830, Thomas Stevens enslaved 31 people in DeKalb County. From among the 45 human beings that he willed to his family upon his death, he gave to Mary’s parents a man named Primus, who he had beaten in the head so severely years previous that he was permanently disabled for the few remaining years of his life. He assigned Elizabeth to his granddaughter Mary Gay upon her marriage or 21st birthday, whichever came first. Mary Gay also inherited her family’s disregard for Black life.

Just before the Yankee occupation of Decatur, Mary tasked her enslaved 16-year-old boy Toby with helping her deliver a trunk of valuables to Atlanta. On the return home from this trip, Toby complained of feeling tired and sick, and when troops were just outside the town, Gay locked her door and insisted that everyone in the household remain outside, including Toby, who again complained of feeling tired and sick. A Yankee doctor diagnosed Toby with measles and gave him medicine. Were it not for the strenuous journey he was forced to take, perhaps the medicine may have helped save his life. As Toby lay dying, Mary asked his forgiveness for her unfair treatment of him, while simultaneously praising his “fidelity and loving interest in our cause and its defenders.”

After the war, a woman who had run away from her family’s enslavement returned and tried to give Mary her children. To this desperate woman, Mary proudly responded, “I am sorry to disappoint you, Frances, but I cannot accept your offer. If slavery were restored and every negro on the American continent were offered to me, I should spurn the offer, and prefer poverty rather than assume the cares and perplexities of the ownership of a people who have shown very little gratitude for what has been done for them.”

Much has been said about Mary Gay’s “mercy and charity,” but she reserved these graces only for those she deemed worthy of such dignity; she granted no such dignity to Black people.

The following are the names of some of the human beings that Mary Gay and her family enslaved across the state of Georgia. These were husbands sold apart from their wives, parents separated from their children. Their lives and struggles have been overshadowed by Mary Gay’s vainglory for far too long. With the upcoming removal of her name from a building in Decatur, perhaps this woman will finally get what she so greatly deserves: obscurity.

Primus

John Glasgow

Mimey

Martha

Hannah

Jack

Amy

Antony

America

Billy

Nancy

Fanny

Sally

Mariah

Peter

Caroline

Bryant

Rosetta

Adeline

Madison

Ellich

Minney

Lottie

Alfred

Rody

Curtis

Clark

Lumpkin

John Brown/“Fed”

Harry

Dempsey

Betty

Sally

Rachel

Madeline

Frances

Malinda

Henderson

Elizabeth

Austin

Emmeline

King

Lewis

Telitha

Toby

Recommended further reading:

“Slave Life in Georgia” by John Brown

“The Southern Past” by W. Fitzhugh Brundage

If you appreciate our work, please become a paying supporter. For as little as $6 a month, you can help us keep you in the loop about your community. To become a supporter, click here.

Want Decaturish delivered to your inbox every day? Sign up for our free newsletter by clicking here.

Decaturish is now on Mastadon. To follow us, visit: https://newsie.social/@Decaturish/.

Decaturish is now on Post. To follow us, visit: https://post.news/decaturish.