- Satellite images show significant growth in the occurrence of algal blooms in contested areas in the South China Sea.

- Images suggest that these algal blooms or phytoplankton overgrowth are linked to the presence of vessels anchored in the area and to island-building activities in the region.

- While satellite images help give a preview of the ecological state of the South China Sea, on-site observations are necessary to validate the findings, experts say.

- Decades of territorial and maritime disputes, however, have limited the conduct of studies and dissuaded the establishment of conservation zones in the South China Sea.

A long-running territorial standoff over the Spratly Islands in the South China Sea has seen vessels dumping enough raw sewage to threaten the marine ecosystem there — and the degradation is extensive enough to be seen from space.

On July 12, U.S.-based geospatial tech company Simularity released satellite images showing a conflagration of algal blooms and phytoplankton sprouting from a trail of human waste dumped by ships anchored in Union Banks, part of the Spratly Islands, which are the subject of rival claims by six governments.

In a follow-up report released Aug. 11, Simularity highlighted the difference in the marine resources of an unoccupied reef and one that has seen human activities, such as Union Banks, which has been occupied by hundreds of Chinese fishing vessels since November last year.

“There is significant evidence that the Union Banks reefs are being damaged by ‘excess nutrients’ and have more reef degrading microalgae than similar reefs which are not occupied,” Simularity said in its Aug. 11 report.

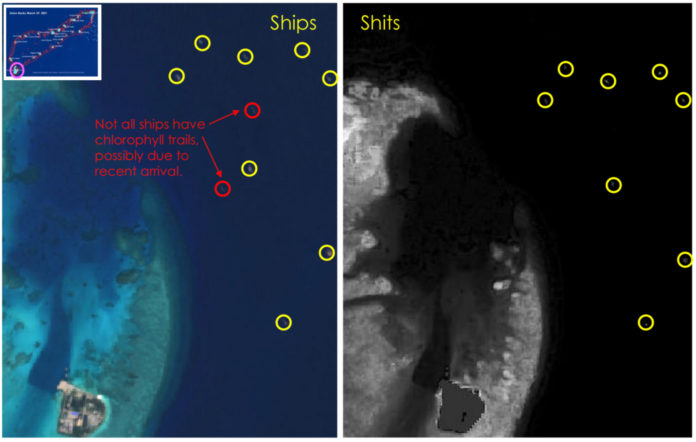

In its first report, the company provided rendered black-and-white images of vessels tailed by concentrations of chlorophyll-a, a predominant type of chlorophyll that can be used to measure the number of algae growing in a water body.

High concentrations of chlorophyll-a typically come from agricultural runoff or poor sewage treatment and can be toxic. As such, chlorophyll-a is a common indicator of degraded water, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Concentrations of these harmful algae can be observed and measured in multispectral satellite images in Union Banks, Simularity said. These images effectively show that the hundreds of ships anchored in the area “are dumping raw sewage onto the reefs.”

The Aug. 11 report, meanwhile, compared chlorophyll-a concentrations using false color key, where the rainbow-like color range is based on light wavelengths determined by values such as temperature or rainfall.

“The damage to the reef in just the last 5 years is visible from space,” Simularity said, adding that the extent of the damage is part of the “well-documented” reef destruction wrought by Chinese construction of artificial islands and harvesting of giant clams in the area. “When the ships don’t move, the poop piles up.”

Keeping tabs on contested waters

The Philippine Space Agency (PhilSA), in an unrelated project from Simularity, has also been conducting space-based observation of the Spratlys, particularly the islands, shoals and reefs claimed by Manila in an area the government calls the West Philippines Sea.

Home to a diverse marine ecosystem, around 30% of the country’s coral reefs are in the Kalayaan Island Group, the Philippine name for the Spratly Islands. The rich fishing ground contributes 27% of the Philippines’ commercial fisheries production and plays a key role in “biochemical cycling and overall biological productivity,” which includes carbon sequestration, PhilSA said.

Amid the ongoing territorial and maritime disputes in the region — largely driven by Chinese expansionism, but with overlapping claims also being made by Vietnam, Malaysia, Brunei and Taiwan — PhilSA and its partners, including the Marine Science Institute of the Philippines (MSI), have initiated projects to record the contested waters’ “ecological and economical” functions.

The initiative includes analyses using both satellite data and ground measurements, such as using chlorophyll-a maps as a gauge for ocean productivity as well as measuring sea surface temperature and salinity. Weather conditions are also monitored, PhilSA said.

“We use readily available moderate- to high-resolution satellite images to study important island features and detect changes, monitor productivity through chlorophyll-a maps, and other important parameters such as sea surface temperature, turbidity, and weather,” said Gay Jane P. Perez, PhilSA’s deputy director-general for space science and technology.

“Utilizing historical satellite data to monitor these changes at a larger scale helps in developing a proactive approach in evaluating the activities in the area and its potential ecological impacts,” Perez said.

‘Loss of dark areas’

In Simularity’s July report, the group counted a total of 236 ships moored in the various formations in Union Banks, a 461-square-kilometer (178-square-mile) stretch at the center of the Spratlys, as of June 17. Four countries have staked claims over portions of Union Banks: the Philippines, China, Vietnam and Malaysia.

China and Vietnam have occupied six reefs and constructed structures there. The report said harmful algae have, in the last five years, taken over distinctive reef features in some of those reefs, including Johnson South Reef, Hughes Reef, Landsowne Reef, Ross Reef and Collins Reef.

The report also shows, in black and white, a “loss of dark areas” and “increasing overall light areas” — indicators of overgrowth algae.

In the August report, Simularity said it has calibrated its methods with ground-truthed water quality and released color-coded maps that, like the previous report, show increased chlorophyll-a concentrations surrounding harbors in the man-made features of Union Banks.

PhilSA’s Perez said satellite images can show higher productivity, like chlorophyll-a concentration, in “shallow, coastal ecosystems and areas with cold, nutrient-rich waters.” In this way, algal blooms from “excessive loading of nutrients compounded by other environmental factors may appear as having anomalously high concentration of chl-a.”

Areas showing higher-than-usual chlorophyll-a values may indicate a higher level of activity, Perez said, adding that these areas become prioritized for investigation, meaning water samples collected at the site can confirm the phenomenon and link it to human activity.

“Fleshy algae on reefs release copious amount of nutrients, which microbes eat,” Simularity said. “These [algae] endanger corals by depleting oxygen from the environment or by introducing diseases. As the corals die off, the algae have even more space to take over, leading to further coral mortality.”

Algal blooms also drive acidification, which increases coral erosion. PhilSA, looking into Simularity’s report, said it has analyzed “potential factors” driving the algal blooms in the area. “This involves understanding the seasonal patterns of productivity in the WPS, looking at potential sources of pollutants, and analyzing the impacts in the coastal habitats,” Perez said.

The PhilSA has presented these analyses to the National Task Force-West Philippines Sea (NTF-WPS), the inter-agency body governing issues related to the country’s western border, but said the release and publication of the findings will depend on the NTF-WPS.

On-site surveys still needed

The disputes, which have escalated in recent years, have largely contributed to the difficulty and the security risk attached to monitoring marine ecosystems in the South China Sea.

Remote-sensing approaches, including using satellite images, have helped fill in the gaps created by the inability to carry out on-site observations. As satellites cover the Earth 365 days a year, the technology provides a robust array of information to aid conservation.

Among Philippine scientists, it has helped in studying and classifying coral habitats and reef features, and allowed the scientists to spot bleaching events from a distance. “With our increasing ability to monitor the vast marine ecosystem, we can maximize our technological resources to protect the ecological integrity of the marine environment amidst the changing climate and man-made impacts,” PhilSA said.

But satellite images shouldn’t be the only data set, experts said. Data collected from on-site surveys are necessary backups to create a reliable map, and a better, more realistic picture of the ecological situation in the South China Sea.

“Collaboration with UP MSI researchers conducting the field survey strengthens our understanding of these important features at various scales,” PhilSA said. “This combined approach of on-site and remote information further provides an efficient assessment of the potential impacts of natural and man-made factors on ecologically and economically important areas in the WPS.”

Satellite images also carry margins of errors. Perez said methods such as chlorophyll-a assessments are “usually calibrated using ground data acquired from the U.S. and European waters.” These waters may differ from coastal waters around the Philippines, Perez said, adding that a recalibration might be necessary for more accuracy. “Different water classes must be considered to further account [for] these similarities and differences in coastal water properties,” Perez said.

Data collected during expeditions provide “valuable sampling points” for verifying and calibrating satellite-sourced data. “With calibrated satellite data, we can further look at the trends and variability of biophysical parameters to gain more insights on the oceanic processes in the WPS,” PhilSA said.

“The importance of understanding the biological processes in the ocean cuts across several aspects, from managing fisheries to mitigating the impacts of harmful algal blooms,” Perez said. “This vital information can then be mobilized to address environmental concerns and climate change impacts as we come up with efficient approaches in managing and ensuring the sustainability of our marine resources.”

Related stories:

Banner image of a green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas) in the Spratly Islands of the South China Sea. Photo courtesy of Greg Asner / Divephoto.org.

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message to the author of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.