With 386 confirmed cases of monkeypox in San Francisco as of August 2, it’s getting to the point where probably just about everyone in the city’s LGBTQ community knows someone who has had or has the virus.

The Bay Area Reporter interviewed several San Francisco gay men about their experiences with the virus and there were numerous common threads. From where many of them contracted it — likely June’s Pride weekend — to its initial flu-like symptoms, monkeypox is becoming more widespread among men who have sex with men in the LGBTQ community. Alarmingly, another thread, though not as common, was the initial reluctance of some medical professionals, even in the San Francisco Department of Public Health, to take the experiences of victims seriously. For one man, the onset, well before monkeypox became widely recognized in San Francisco, was terrifying.

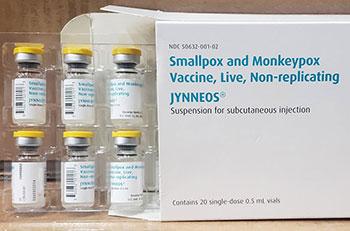

Fortunately, and unlike COVID in the earliest days of that pandemic, there’s a vaccine for monkeypox. Unfortunately, it’s in short supply as the experiences of the many men queueing up at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital and Trauma Center at 5 a.m. to get the shot would attest. And, as figures from the DPH show, at least in San Francisco, the outbreak has affected only men — including some trans men and some who indicated “other” for their gender — so far.

That said, it’s hitting the Latino community particularly hard. While Latinos comprise just over 15% of San Franciscans, Latino men make up nearly 28% of confirmed monkeypox cases, according to demographic statistics published by DPH July 29 (as of that date, there were only 261 confirmed cases in the city). White men comprised just over 41% of cases, while Asian men accounted for 10%, and Black men 3.8%. Other/multi-ethnic men, as well as men of unknown ethnicity comprised the remaining 12.2%. Non-Latino Caucasians make up 38% of San Francisco’s population, while Asians comprise 37.2% and African Americans 5.7%, according to United States Census figures released in 2021.

As of yet, in the United States, there have been no known fatalities related to monkeypox although two have been reported in Spain, and more than 70 in Africa, where two strains of the virus are present, including the more virulent central African clade (a clade is a group of organisms which have evolved from a common ancestor). Both the central African or Congo Basin clade and the milder west African clade have been identified in the United States but the west African clade is, so far, more widespread, health officials said.

“The case-fatality ratio for the West African clade of monkeypox is reported to be 1% and might be higher in immunocompromised persons,” according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

It begins like COVID

While most of the men interviewed by the B.A.R. reported relatively easy experiences with the virus — and the key word here is relatively — being sick is no picnic. Each of the men was hit at first with flu-like symptoms, which led some to think they might be coming down with COVID.

When James Zengerle, a 29-year-old grad student, came home from work in mid-July, he wasn’t feeling great.

“That day, I went to work and came home,” he said. “Took a shower, and got really bad chills.”

The symptoms felt like COVID, said Zengerle, which he had had only the month before. He slept for 16 hours for the first two days, and had back and neck pain.

Other guys experienced similar symptoms and, during that first couple of weeks when monkeypox was making its way into the community before being identified, many of those interviewed said they assumed they were coming down with COVID, as well. Zengerle took COVID tests, which came back negative.

Property manager Daniel Blair, 31, had a similar experience.

“I started experiencing symptoms in the first week of July,” Blair said. “I woke up and I had a fever, body aches. I didn’t feel myself … I swore it was COVID.”

Like Zengerle, Blair took a couple of COVID tests that came back negative. He had decided against immediately going to the doctor, though.

“I kept telling myself ‘If it gets worse, I’d go to the doctors,'” Blair said. He checked in with some of his sexual partners and they told him they were feeling fine.

At that point, Blair didn’t have any of the telltale lesions associated with monkeypox but he was beginning to experience internal pain, which is another marker of the virus. Many of those who become sick experience lesions in their rectums and around their anuses, making passing stool difficult, if not incredibly painful.

While the symptoms were unusual, Blair said, he figured it was “because of everything else going on.”

By the time Monday rolled around, he was still sick. He had a virtual appointment with his doctor who, after hearing Blair’s symptoms, told him it was hemorrhoids. Blair said he was frustrated with the doctor’s advice, which was to “give it a couple days.”

“I got misdiagnosed,” said Blair.

‘I felt some fear for my life’

Monkeypox is not new. Human cases of monkeypox have been seen since 1970 in Africa, likely having crossed over from animals. In 2018, according to the University of Minnesota’s Center for Disease and Research Policy, human-to-human transmission had been documented but “monkeypox does not transmit readily among humans; human disease is most often linked to eating contaminated bush meat or coming into contact with infected animals.”

Human-to-human transmission had been documented by that point, however, as CDRP noted, and one case had been documented in Britain that year. A Nigerian “likely contracted the rare viral infection in that country before traveling to the United Kingdom” in 2018, according to CDRP.

The next time monkeypox would show up in Britain would be May 6, 2022. Before the end of the month, additional cases would appear in Spain and Belgium. It likely showed up in San Francisco before the end of May, as well. That was certainly when Joshua Alexander experienced it.

Like Blair and Zengerle, Alexander’s case began with flu-like symptoms around May 25. “I had flu-like symptoms: backache, chills, swollen lymph nodes, exhaustion,” he said.

Then, about five days later, a sore appeared on his nose.

“That seemed unusual,” said Alexander, 41, “and then it wasn’t getting better.”

It wouldn’t get better before it got worse. The lesions had begun to appear in more places on his face. In fact, he didn’t experience lesions anywhere else on his body but his head. They showed up on his face, on his scalp. He tried taking Valtex, an antiviral often used for herpes, shingles, and genital herpes. At that point, however, he hadn’t made the connection with monkeypox, he said.

“It was rough,” Alexander said. “When, like, the second and third sores appeared, my experience was ‘Oh, shit. I have no idea what this is, it’s spreading.’ I felt some fear for my life. What went through my head was, what if this is something no one knows how to help me with?”

Then, at the suggestion of his partner, Dr. Drew Maris, a family physician, they Googled photos of monkeypox. That wasn’t quite as helpful as they had hoped as the photos depicted lesions like round bubbles on the skin, and his weren’t really like that, said Alexander. Maris, despite his close relationship with Alexander, did not contract the virus.

Alexander made his first visit to urgent care at SFGH on June 1. The first diagnosis: impetigo, a highly contagious skin infection that typically shows up on infants and young children, often around the nose and mouth. He was given medication for that, but on a second visit, on June 2, another nurse practitioner thought it might be Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, a source for staph infections that can be very difficult to treat. The nurse then told him he needed to be on a different medication.

“It felt like she just wanted me out of her face,” said Alexander.

On his third visit on June 6, he asked for a monkeypox test from a third nurse practitioner. The nurse first had to call DPH for advice, Alexander said, and then he took samples to test for a variety of things. Later, Alexander got a call from the communicable diseases office of DPH and was told they had looked at his case but they were not going to test the samples for monkeypox.

The photos of the lesions didn’t look like monkeypox, they told him.

Stonewalled by DPH

Maris, who has a private practice in Marin County, wrote an email that same day to Dr. Darpun Sachdev, an infectious disease specialist at SFGH. In the email, Maris tells Sachdev he had sent his partner, whom he describes as his patient, to Urgent Care specifically to be tested for monkeypox as he had been observing the spread of the lesions since “day two of their appearance” and, given that Alexander fit the profile of at-risk groups, and the lesions “have progressed precisely according to the European/American presentation of the disease” he felt a test for monkeypox was in order.

Maris goes on to insist that SFGH perform the tests Alexander had requested.

“Mr. Alexander informed me that your department has declined testing despite samples being collected,” he wrote. “While I understand that even if this is monkey pox (sic) Mr. Alexander should recover without incident, the risk to public health is real and your department is charged with protecting same.

“I disagree with your assessment and refusal to run the assay and I am noting it in the patient’s chart,” Maris continued. “As Urgent Care already obtained the specimens and this test is clinically indicated I request that the assay be performed.”

The following day, June 7, Alexander visited the dermatology department where he found himself the subject of a group visit by several personnel curious about his case.

“All these people came in to look at me,” he said. The dermatologist took a six-millimeter sample from his cheek and sent it off.

“The head guy (I think that’s the guy attending?) was the one who said it didn’t look like monkeypox even though he had never seen monkeypox before,” Alexander later told the B.A.R. in an email.

Those samples were not tested for monkeypox, despite the urging of the dermatologist.

Alexander and his partner Maris were left angered and frustrated by their experiences with SFGH and DPH.

“As a physician, I really felt we were being stonewalled by DPH,” said Maris. “I can understand the frustration of the dermatologist. We keep sending the tests and they keep refusing them.”

In a statement to the B.A.R., DPH said that its ability to test for monkeypox was “limited due to state lab capacity for volume and a very strict criteria was applied by the state.”

Although DPH didn’t outline the criteria, the statement goes on:

“At the beginning of the outbreak, all samples had to be sent to the state lab in Richmond for orthopox testing. After the samples were processed by the state, the positive samples were then shipped to the CDC for confirmation. California Department of Public Health’s (CDPH) approval was required for all tests, according to strict criteria established by the state. SFDPH provided clinicians and facilitated transportation of samples to the state lab. There are various reasons why a test might have not been processed, including mislabeled samples or the individual not fitting the very strict criteria established by the state for testing at the time.”

By early July, the ability to test for monkeypox had increased and the department was “no longer constrained by state resources,” the statement continued. “The San Francisco Public Health lab is able to test and confirm monkeypox specifically, though samples are still sent to CDC for additional characterization.”

Help keep the Bay Area Reporter going in these tough times. To support local, independent, LGBTQ journalism, consider becoming a BAR member.