On a July 1991 morning, a few days after Paul Broussard was murdered, Houston Post columnist Juan R. Palomo read the coverage of the gay-bashing incident that galvanized the LGBTQ rights movement in the city. He remembers Broussard’s mother, Nancy Rodriguez, telling a reporter colleague at the newspaper: “I don’t understand.” Palomo, though, did understand. And he knew then and there what the topic of his next column would be.

Palomo understood because he too is gay. While many of his colleagues at the Post knew, he was closeted to his editors as well as his readers. The prospect of coming out was something that loomed over Palomo for a long while, something he knew he had to do eventually but didn’t feel any urgency to. Broussard’s killing became the catalyst, but his revelation would lead to a weeks-long debacle in which the Post censored him, fired him, then—after much public outrage—rehired him.

Read more about Houston in the ’90s

Broussard’s murder came at a time when the LGBTQ community was fighting for acceptance in Texas and nationwide. A group of 10 teenagers were convicted of beating and stabbing the 27-year-old banker to death on the night of July 4 outside a Montrose nightclub, sparking a key turning point in Houston’s gay rights movement. “As a result of local gay activism, the Houston City Council unanimously passed a resolution calling for a gay-inclusive state-level hate crimes bill,” writes historian J.D. Doyle in Houston LBGT history. “The Houston Police Department also added sexual orientation to the list of biases motivating a hate crime.”

As a response to Broussard’s killing, HPD’s “Operation Vice Versa” had officers go undercover as homosexual men, only to get beaten up as well. Just a year earlier, the Houston Pride Parade welcomed its very first corporate sponsors, including Budweiser. In a 2022 world where even the Shell gas station on Richmond and Montrose Boulevard sported a rainbow logo this past Pride Month, it may be difficult to remember the importance of these milestones. Later in the 1990s, an incident in Houston led to the sodomy laws of Texas and 13 other states to be struck down by the Supreme Court in 2003’s landmark Lawrence v. Texas case.

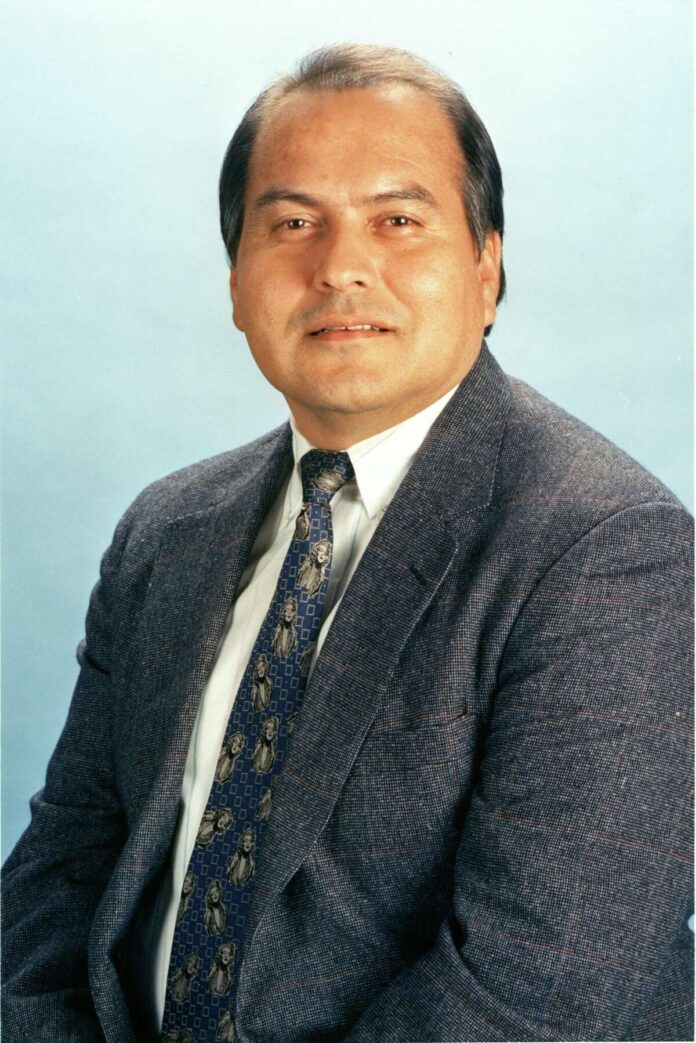

As a columnist for the Houston Post, Juan R. Palomo covered local-interest, Latino and gay issues.

HP staff/Houston Chronicle files

Palomo hadn’t so much as been to a gay bar in Houston at the time, and wasn’t involved in the community’s activism. This was partly due to him being closeted, but also because he was a journalist and, he admits, quite introverted. But Palomo did write about gay issues frequently, always feeling a tinge of guilt that he was a fraud passing as a heterosexual man who supported gay rights, he says.

The Crystal City, Texas, native had a distinguished journalism career before becoming a columnist. After teaching art in a San Marcos school for two years, he quit to join a newly formed Mexican American newspaper his friends founded called La Otra Voz. He created artwork and graphics, then began writing, which he quickly realized he took great pleasure in and was good at. He then worked as a reporter in Kyle before leaving for Washington, D.C., to do a master’s in journalism at American University. An internship in the Houston Post’s D.C. bureau followed, and after a brief stint at USA Today, he returned to the Post in the early 1980s.

In 1983, the Toronto Sun bought the Houston Post and, as Palomo explains it, the leadership wanted to set up an office in Barbados to pay fewer taxes. They just needed one reporter to be stationed there. “They looked around and asked: ‘Who’s got a passport, who’s not married and who speaks Spanish?’ I was the only one who qualified,” Palomo said. Coincidentally, it was the same year as the U.S. invasion of Grenada, which he reported on for the Post. He traveled to almost all Central American and Caribbean countries during his time there, and returned to D.C. in 1985, covering the senate, NASA and other government agencies.

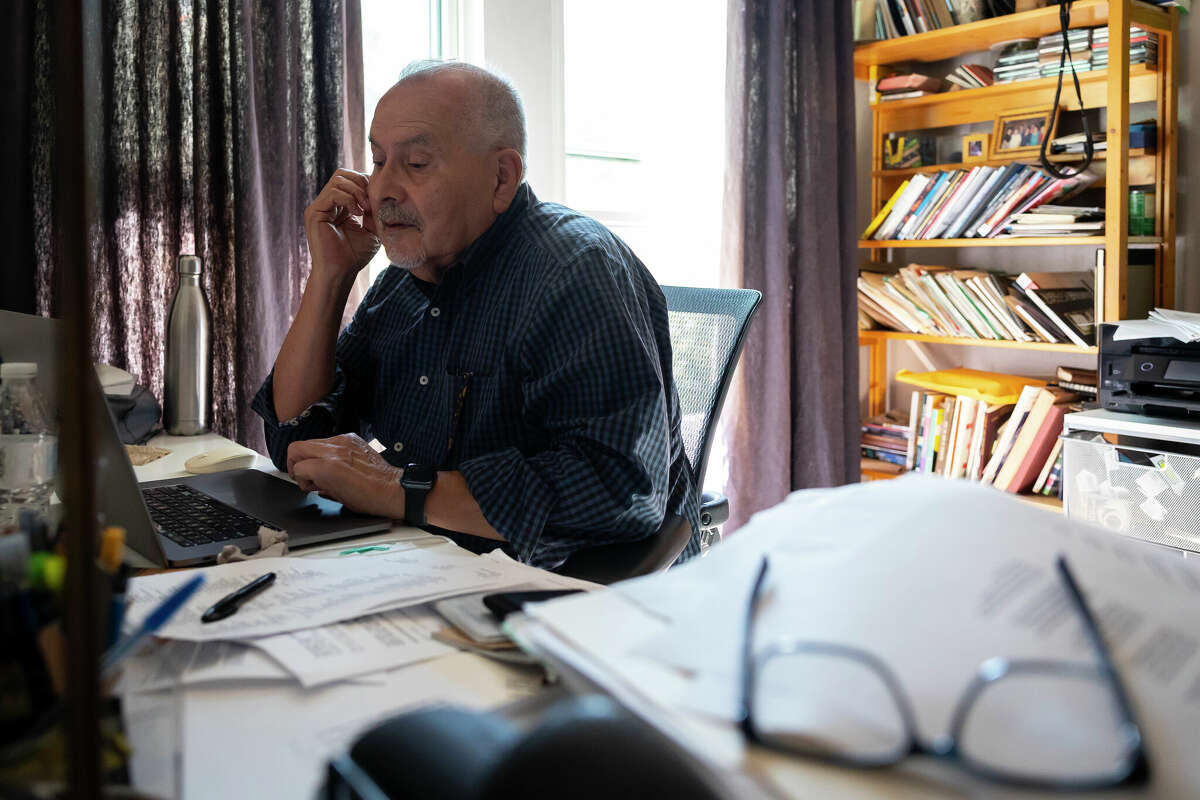

Juan R. Palomo still lives in Houston, his home since the early 1990s.

Annie Mulligan/Contributor

He did this for five years, all the while lobbying to be a columnist, a long-time dream of his. Finally, the Post gave him the opportunity: three columns a week on the front page of the local section, based in Houston. Palomo wrote mostly local-interest stories, including but not limited to Latino and gay issues. He never wanted to be pigeonholed, he says.

Palomo had been a columnist for less than a year when Broussard was killed. In the wake of the tragedy, he sat down to pen what would become his most important column, a plea for Houstonians not to stay silent about such a horrific hate crime. It flowed out of him, he remembers, one of the easiest columns he’s ever written, feeling a huge relief after he filed it. In the final paragraph, Palomo came out as gay—but subscribers reading the paper the next morning would never see it printed.

The call from his editor arrived quickly. Readers aren’t ready for something like this, Palomo remembers him saying, and his coming-out was removed in the edit. He was disappointed, having naively thought perhaps Post leadership would have seen this as a great opportunity to show how open-minded the paper was. But Palomo knew there was no point arguing. His editors were always worried about losing readership, he says, often bringing letters from angry readers to his desk threatening to cancel their subscriptions over whatever column he had just written. “I think the Post was willing to tolerate any column about anything, as long as the phone didn’t start ringing,” Palomo said.

The next day, Palomo received hundreds of voicemails from readers, all praising his column. But to him, it was just “a continuation of the fraud.” Palomo had given a copy of the column to a colleague, knowing the original would end up in the right hands if needed. Eventually, it did, those of Tim Fleck, a Houston Press reporter who published a story with his original coming-out kicker. By the end of August, Palomo was fired.

After working for decades as a reporter and columnist, then for the oil industry, Juan R. Palomo retired in 2012 and became a poet.

Annie Mulligan/Contributor

For a paper so concerned about not rocking the boat, that’s exactly what the Post got. Palomo’s firing made national headlines, including in the New York Times and the Washington Post. Most importantly, local advocates rallied around him, including Latinos and LGBTQ groups already activated by the murder of Broussard earlier that summer. The Houston chapters of the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC) and AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) were among the leading voices, as well as community members like the owners of Casa Ramirez, a Mexican folk art store that’s still around today.

“You fired one of our own—gay, Latino—and we’re not going to stand for it,” Linda Morales, a prominent lesbian activist who worked for a state senator at the time, remembers thinking. She hadn’t known Palomo was gay; she knew him as a great writer and columnist whom she enjoyed reading, and who had interviewed her weeks prior for a story about her being the Pride Parade’s Grand Marshal. She saw the Post’s actions as hypocritical: Allowing Palomo to write about gay issues, but not allowing him to come out himself. “That was the political landscape of Texas at that time,” she said. “But people still stood up and made their voices heard.”

Morales and others organized a press conference and demonstration outside the Houston Post (now the Houston Chronicle building). Attendees tore the newspaper in half as a sign of protest, and readers across the city wrote letters and called to cancel their subscriptions. There were even protests outside then-Post editor Charlie Cooper’s house. But the most moving moment to Palomo was when, right around deadline, a number of his colleagues at the Post got up from their desks, walked out, grabbed picket signs and joined the protest outside the building.

The Post editors had been concerned about angry letters and canceled subscriptions, and they got them—in overwhelming support of Palomo. Almost 10 days after firing him, facing mounting criticism, the paper rehired him, with a caveat: Palomo says they “punished” him by moving him to the op-ed page, writing two editorials a week instead of three columns. But he didn’t mind.

“I think if we had been silent, they would not have brought him back,” Morales said. “They needed to feel that pressure. They needed to feel that shame.”

Long-time Houstonians know how this story ends: The Houston Chronicle bought the Post in 1995 and ceased its publication. Palomo was unemployed for several months, covered religion for the Austin American-Statesman for a year, then moved back to San Marcos and freelanced. Eventually, he went to work in the oil industry, a job without which he would have been “on the streets begging for money,” he says.

Sipping a cold brew at Campesino Coffee House in Montrose on a recent August morning, Palomo, now 76, says he doesn’t think about the incident all that much anymore, and as the years go by, fewer and fewer people in Houston remember him. After retiring in 2012, he turned his writing skills to another, completely new-to-him medium: poetry.