CLARKSVILLE, TN (CLARKSVILLE NOW) – In the 1980s, being gay in Clarksville meant your private life had to stay extremely private. For 62-year-old Amanda Leigh, a lot of that stemmed from widespread misconceptions about what being gay actually meant.

“Back then, a lot of people just didn’t know what gay meant. So many people thought that being gay meant you were a pedophile, a predator, you wanted their children, you wanted to convert everybody,” Leigh told Clarksville Now. “They didn’t know what it meant and they weren’t interested in learning.”

In the last 40 years, attitudes have changed drastically; so much so that Clarksville now has an openly queer person serving on the City Council in Ward 11’s Ashlee Evans. During Pride month in June, Clarksville Now dug into the local history of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender life. While we uncovered several moments of joy and prosperity, we also found times of discrimination and danger.

This is not a comprehensive history of LGBTQ life in Clarksville – there’s no doubt that LGBTQ life existed long before 1979. Instead it’s a snapshot of moments that have helped define Clarksville’s legacy in the struggle for equality.

1979: APSU Student Coalition for Gay Rights lawsuit

In the fall of 1978, several Austin Peay State University students organized a group called the Student Coalition for Gay Rights.

The students applied for recognition through the university’s Student Government Association, an official recognition would allow the group to conduct meetings on campus and apply for funds to host events.

While the group’s application was initially approved, SCGR received a letter in February 1979 from the vice president for Student Affairs denying them recognition, according to documents at APSU’s Archives and Special Collections at Woodward Library. Reasons for denying the group recognition included worries about what the community would think, and that allowing the group to operate would mean the university endorsed homosexuality.

Homosexuality was still illegal at this point, and it remained illegal in Tennessee until 1996.

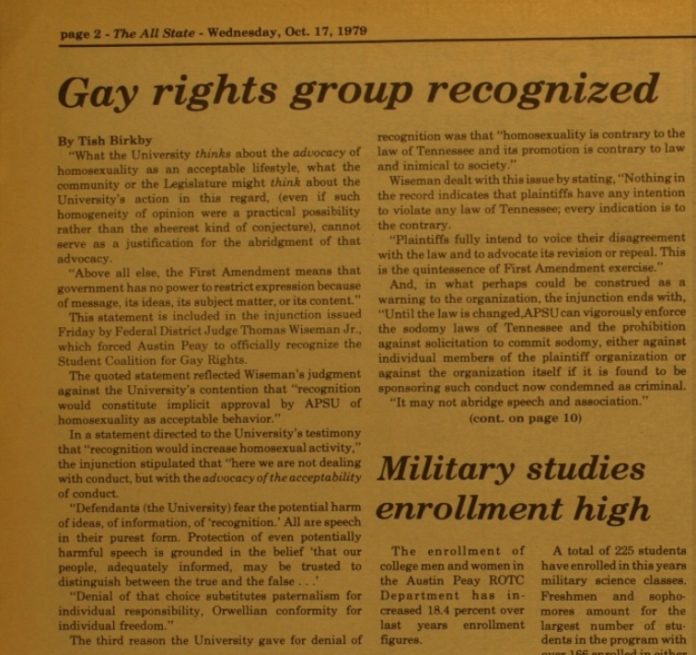

After a federal court battle, the university was forced to recognize the group in October 1979, when a judge ruled that the students’ First Amendment rights were abridged.

With that, the SCGR became Tennessee’s first state university student organization centered around gay rights. Additionally, the legal battle would become a landmark case in First Amendment rights and was taught at law schools including Yale.

Bill Dannenmaier, one of the plaintiffs in the case, said his involvement as a straight man helped strengthen SCGR’s case.

“It helped to keep the discussion about freedom of assembly, not about the perception or the ‘lifestyle’ or behavior. We now know ‘lifestyle’ as an expression is kind of bigoted, because it’s just who people are. It’s not something they chose,” Dannenmaier told Clarksville Now.

“It’s a better world, and, in part, that case helped to make it that way,” he said.

The group has changed names over the last 40 years and continues today on the APSU campus as the Sexuality and Gender Alliance.

1979: First gay club opens

Where Kimo’s Hawaiian Grill stands in downtown Clarksville used to be a small, members-only club called Cooper’s General Store. Over the door hung the acronym C.G.S., which to the general public meant Cooper’s General Store.

To those who were club members, though, C.G.S. meant Clarksville Gay Society. It opened Oct. 27, 1979, and it was established as a private club.

While CGS was not open long, it was a place of gay celebration and liberation, and it featured drag performances. Clarksville drag queen Amanda Leigh, now 62, was on the board of directors at CGS. She said privacy was necessary due to both public perception and the laws of the time.

Acting on one’s homosexuality was still illegal in Tennessee; the anti-sodomy law wasn’t struck down by the state’s Supreme Court until 1996, almost 20 years later. Leigh and others have said that police and Army Criminal Investigation Division officers entered the club multiple times to intimidate members. Clarksville Now could not find documentation about those claims.

Due to word of mouth about a potential crackdown on the club, CGS closed on April 6, 1980.

In July 1981, the Haberdashery opened, one of several gay bars that opened and closed in downtown Clarksville during the 1980s and ’90s.

1981: Trice Landing bust

While Trice Landing Park nowadays is known for its fishing boat ramp and view of the Cumberland River, it was once a prime location for gay “cruising” and a high-profile police raid.

Officers with the Clarksville Police Department’s Vice Squad set up sting operations to arrest gay men who would go to the park and look for hookups, according to Leaf-Chronicle archives.

During the spring of 1981, an undercover police operation resulted in the arrest of 14 men. They were charged with offenses such as crimes against nature, attempting to commit a felony and common law lewdness.

The Leaf-Chronicle repeatedly published the mens’ names, addresses, and often, their places of work in coverage of the arrests and court cases. This was standard practice at the time; the practice has since changed.

Several of the men received pretrial diversions, and a handful pleaded guilty.

One of the men, Pete Wenger, a professor at APSU, died Jan. 30, 1982, after a fall from a cliff along the Red River. He had left his home the night before, threatening suicide because of the media coverage.

1992: Murder of P’Knutts

P’Knutts was a 38-year-old drag queen living in Clarksville. Born Jerry Cope, P’Knutts worked as a bartender at the Brown Derby, a tavern then located at 321 Commerce St.

On the evening of Jan. 13, 1992, she was closing for the night when it is believed a robbery took place. In the process, P’Knutts was stabbed and killed, according to Leaf-Chronicle archives. The murder is still unsolved.

Leigh and P’Knutts were the best of friends, and Leigh told Clarksville Now she had found some peace in the almost 30 years since she lost her friend.

“It is still so heartbreaking, and I continue to miss her dearly,” Leigh said. “In my heart, I know who did it, but both of them are dead.”

In Leigh’s home hangs a painted portrait of her friend. And after the murder, Leigh said attitudes around town changed drastically about drag artists and transgender people.

1999: Murder of Pfc. Barry Winchell

Pfc. Barry Winchell was a 21-year-old gay solider stationed at Fort Campbell. On July 5, 1999, after a fight with fellow soldiers that revolved around Winchell’s sexuality, Winchell was beaten in his sleep with a baseball bat. The following day, Winchell died at Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

Winchell’s death garnered national attention, and specifically it led to a reckoning about the ‘Don’t ask, don’t tell’ military policy, instituted by then-President Bill Clinton in 1994, which allowed LGBTQ people to serve in the military as long as they were not public about their sexual orientation.

Months later, Clinton admitted the policy’s failures and cited Winchell’s death in questioning how the policy had been implemented, according to New York Times archives.

Winchell’s death also prompted the Pentagon to order personnel training to prevent harassment of LGBTQ people in 2000, the Times reported.

Two soldiers were charged: Pvt. Calvin N. Glover was found guilty of premeditated murder and sentenced to life with the possibility of parole. Spc. Justin R. Fisher was sentenced to 12 1/2 years as part of a plea bargain.

In 2010, the “Don’t ask, don’t tell” policy was repealed by President Barack Obama, allowing gay, lesbian and bisexual service-members to be open about their sexualities.

2005: Clarksville’s first Pride

In 2005, David Shelton organized the first Pride celebration, which took place on May 21. It was sponsored by the Christian Community Church of Clarksville and held at what was then Fairgrounds Park, now Liberty Park.

Over 800 people showed up the first year, and 1,200 attended the next year, in 2006.

While it was a fun, community-oriented event featuring inflatables, face-painting and music, Shelton said the deaths of Winchell and P’Knutts were driving motivators.

“What we wanted to do with Pride was to try to do what we could to address both of those events. At the time it was also ‘Don’t ask, don’t tell,’ and there was no marriage equality. … There are all of these things that we have today that I hope nobody is taking for granted,” Shelton told Clarksville Now. “That was the environment, so if we knew we had Pride in Clarksville, we had to honor both of those people.”

Tributes were paid, and a portrait of P’Knutts was auctioned – the same one that now hangs in Leigh’s home.

“The whole event was about Pride, but not only to recognize where we had come from, but also to say to the community as a whole, ‘We are here, we are queer. Now, how can we help?’” Shelton said.

2015: First same-sex marriage in Clarksville

On June 26, 2015, with a 5-4 decision in Obergefell v. Hodges, the U.S. Supreme Court declared same-sex marriage legal in all 50 states.

That day, the first to arrive at the Montgomery County Clerk’s Office to be wed were Travis VanZant and his soon-to-be husband, Michael.

“We were planning on going to another state to get married, and it just so happened that they legalized it in all 50 states,” Travis said of he and Michael’s spontaneous decision.

They had been together six months when they got married, and they just celebrated their sixth anniversary.

Although VanZant and his husband have faced quite a few trials, including trouble adopting children and securing health insurance through each other’s jobs, they have fostered several kids together and continue hoping to adopt one day.

“Being able to be with the person I love, and not having to worry anymore, is amazing,” Travis said.

MORE: LGBTQ Clarksville on what it means to go from self-acceptance to pride