In the midst of a pandemic and a national uprising, Teeth Logsdon-Wallace was kept awake at night last summer by the constant sounds of helicopters and sirens.

For the 13-year-old from Minneapolis who lives close to where George Floyd was murdered in May 2020, the pandemic-induced isolation and social unrest amplifed his transgender dysphoria, emotional distress that occurs when someone’s gender identity differs from their sex assigned at birth. His billowing depression landed him in the hospital after an attempt to die by suicide. During that dark stretch, he spent his days in an outpatient psychiatric facility, where therapists embraced music therapy. There, he listened to a punk song on loop that promised how things would soon “get better.”

Eventually they did.

Logsdon-Wallace, a transgender eighth-grader who chose the name Teeth, has since “graduated” from weekly therapy sessions and has found a better headspace, but that didn’t stop school officials from springing into action after he wrote about his mental health. In a school assignment last month, he reflected on his suicide attempt and how the punk rock anthem by the band Ramshackle Glory helped him cope — intimate details that wound up in the hands of district security.

In a classroom assignment last month, Minneapolis student Teeth Logsdon-Wallace explained how the Ramshackle Glory song “Your Heart is a Muscle the Size of Your Fist” helped him cope after an attempt to die by suicide. In the assignment, which was flagged by the student surveillance company Gaggle, Logsdon-Wallace wrote that the song was “a reminder to keep on loving, keep on fighting and hold on for your life.” (Photo courtesy Teeth Logsdon-Wallace)

The classroom assignment was one of thousands of Minneapolis student communications that got flagged by Gaggle, a digital surveillance company that saw rapid growth after the pandemic forced schools into remote learning. In an earlier investigation, The 74 analyzed nearly 1,300 public records from Minneapolis Public Schools to expose how Gaggle subjects students to relentless digital surveillance 24 hours a day, seven days a week, raising significant privacy concerns for more than 5 million young people across the country who are monitored by the company’s digital algorithm and human content moderators.

But technology experts and families with first-hand experience with Gaggle’s surveillance dragnet have raised a separate issue: The service is not only invasive, it may also be ineffective.

While the system flagged Logsdon-Wallace for referencing the word “suicide,” context was never part of the equation, he said. Two days later, in mid-September, a school counselor called his mom to let her know what officials had learned. The meaning of the classroom assignment — that his mental health had improved — was seemingly lost in the transaction between Gaggle and the school district. He felt betrayed.

“I was trying to be vulnerable with this teacher and be like, ‘Hey, here’s a thing that’s important to me because you asked,” Logsdon-Wallace said. “Now, when I’ve made it clear that I’m a lot better, the school is contacting my counselor and is freaking out.”

Jeff Patterson, Gaggle’s founder and CEO, said in a statement his company does not “make a judgement on that level of the context,” and while some districts have requested to be notified about references to previous suicide attempts, it’s ultimately up to administrators to “decide the proper response, if any.”

‘A crisis on our hands’

Minneapolis Public Schools first contracted with Gaggle in the spring of 2020 as the pandemic forced students nationwide into remote learning. Through AI and the content moderator team, Gaggle tracks students’ online behavior everyday by analyzing materials on their school-issued Google and Microsoft accounts. The tool scans students’ emails, chat messages and other documents, including class assignments and personal files, in search of keywords, images or videos that could indicate self-harm, violence or sexual behavior. The remote moderators evaluate flagged materials and notify school officials about content they find troubling.

In Minneapolis, Gaggle flagged students for keywords related to pornography, suicide and violence, according to six months of incident reports obtained by The 74 through a public records request. The private company also captured their journal entries, fictional stories and classroom assignments.

Gaggle executives maintain that the system saves lives, including those of more than 1,400 youth during the 2020-21 school year. Those figures have not been independently verified. Minneapolis school officials make similar assertions. Though the pandemic’s effects on suicide rates remains fuzzy, suicide has been a leading cause of death among teenagers for years. Patterson, who has watched his business grow by more than 20 percent during COVID-19, said Gaggle could be part of the solution. Though not part of its contract with Minneapolis schools, the company recently launched a service that connects students flagged by the monitoring tool with teletherapists.

“Before the pandemic, we had a crisis on our hands,” he said. “I believe there’s a tsunami of youth suicide headed our way that we are not prepared for.”

Schools nationwide have increasingly relied on technological tools that purport to keep kids safe, yet there’s a dearth of independent research to back up their claims.

Like many parents, Logsdon-Wallace’s mother Alexis Logsdon didn’t know Gaggle existed until she got the call from his school counselor. Luckily, the counselor recognized that Logsdon-Wallace was discussing events from the past and offered a measured response. His mother was still left baffled.

“That was an example of somebody describing really good coping mechanisms, you know, ‘I have music that is one of my soothing activities that helps me through a really hard mental health time,’” she said. “But that doesn’t matter because, obviously, this software is not that smart — it’s just like ‘Woop, we saw the word.’”

‘Random and capricious’

Many students have accepted digital surveillance as an inevitable reality at school, according to a new survey by the Center for Democracy and Technology in Washington, D.C. But some youth are fighting back, including Lucy Dockter, a 16-year-old junior from Westport, Connecticut. On multiple occasions over the last several years, Gaggle has flagged her communications — an experience she described as “really scary.”

“If it works, it could be extremely beneficial. But if it’s random, it’s completely useless.”

—Lucy Dockter, 16, Westport, Connecticut student mistakenly flagged by Gaggle

On one occasion, Gaggle sent her an email notification of “Inappropriate Use” while she was walking to her first high school biology midterm and her heart began to race as she worried what she had done wrong. Dockter is an editor of her high school’s literary journal and, according to her, Gaggle had ultimately flagged profanity in students’ fictional article submissions.

“The link at the bottom of this email is for something that was identified as inappropriate,” Gaggle warned in its email while pointing to one of the fictional articles. “Please refrain from storing or sharing inappropriate content in your files.”

Gaggle emailed a warning to Connecticut student Lucy Dockter for profanity in a literary journal article. (Photo courtesy Lucy Dockter)

But Gaggle doesn’t catch everything. Even as she got flagged when students shared documents with her, the articles’ authors weren’t receiving similar alerts, she said. And neither did Gaggle’s AI pick up when she wrote about the discrepancy in a student newspaper article where she included a four-letter swear word to make a point. In the article, which Dockter wrote with Google Docs, she argued that Gaggle’s monitoring system is “random and capricious,” and could be dangerous if school officials rely on its findings to protect students.

Her experiences left the Connecticut teen questioning whether such tracking is even helpful.

“With such a seemingly random service, that doesn’t seem to — in the end — have an impact on improving student health or actually taking action to prevent suicide and threats” she said in an interview. “If it works, it could be extremely beneficial. But if it’s random, it’s completely useless.”

Some schools have asked Gaggle to email students about the use of profanity, but Patterson said the system has an error that he blamed on the tech giant Google, which at times “does not properly indicate the author of a document and assigns a random collaborator.”

“We are hoping Google will improve this functionality so we can better protect students,” Patterson said.

Back in Minneapolis, attorney Cate Long said she became upset when she learned that Gaggle was monitoring her daughter on her personal laptop, which 10-year-old Emmeleia used for remote learning. She grew angrier when she learned the district didn’t notify her that Gaggle had identified a threat.

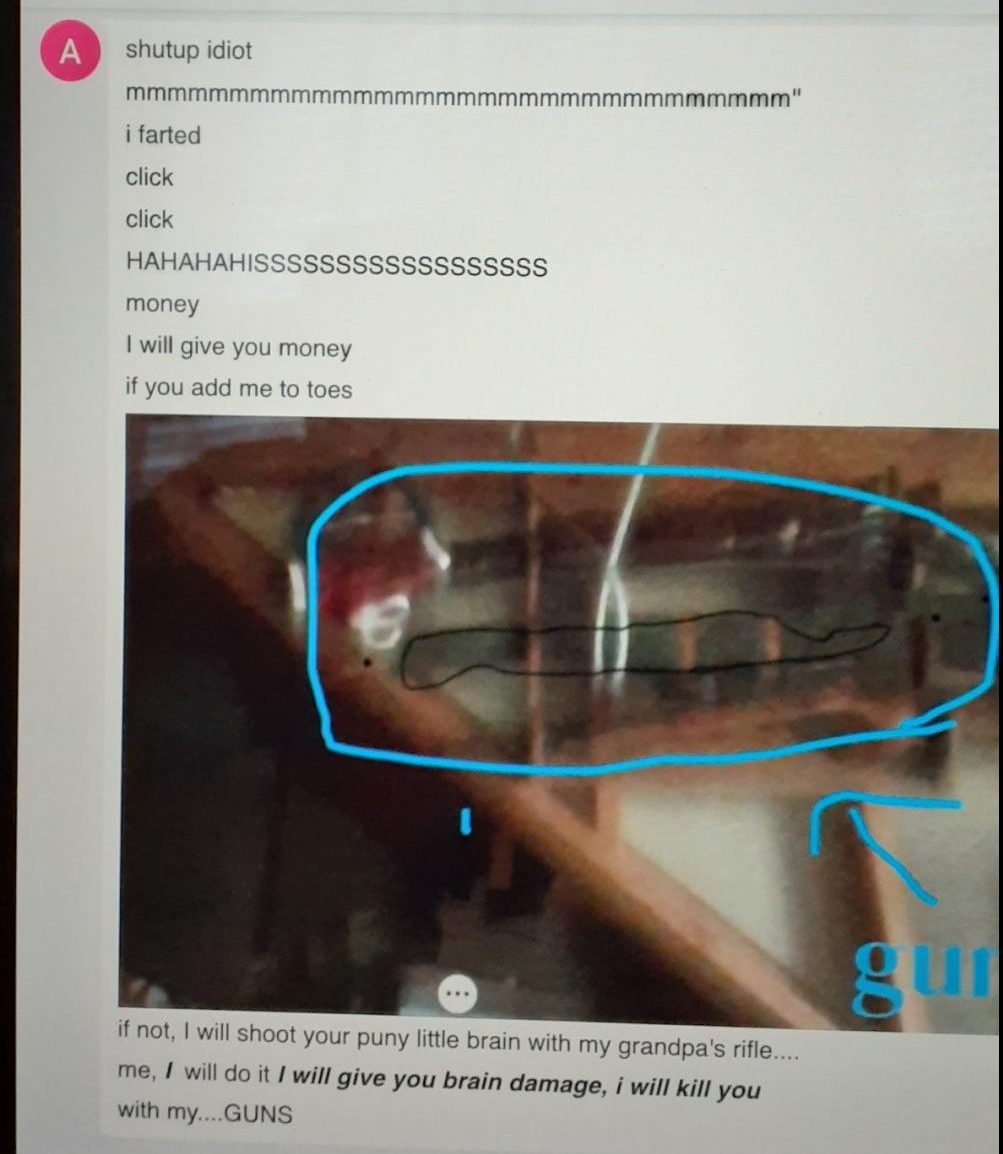

This spring, a classmate used Google Hangouts, the chat feature, to send Emmeleia a death threat, warning she’d shoot her “puny little brain with my grandpa’s rifle.”

Minneapolis mother Cate Long said a student used Google Hangouts to send a death threat to her 10-year-old daughter Emmeleia. Officials never informed her about whether Gaggle had flagged the threat. (Photo courtesy Cate Long)

When Long learned about the chat, she notified her daughter’s teacher but was never informed about whether Gaggle had picked up on the disturbing message as well. Missing warning signs could be detrimental to both students and school leaders; districts could be held liable if they fail to act on credible threats.

“I didn’t hear a word from Gaggle about it,” she said. “If I hadn’t brought it to the teacher’s attention, I don’t think that anything would have been done.”

The incident, which occurred in April, fell outside the six-month period for which The 74 obtained records. A Gaggle spokesperson said the company picked up on the threat and notified district officials an hour and a half later but it “does not have any insight into the steps the district took to address this particular matter.”

Julie Schultz Brown, the Minneapolis district spokeswoman, said that officials “would never discuss with a community member any communication flagged by Gaggle.”

“That unrelated but concerned parent would not have been provided that information nor should she have been,” she wrote in an email. “That is private.”

‘The big scary algorithm’

When identifying potential trouble, Gaggle’s algorithm relies on keyword matching that compares student communications against a dictionary of thousands of words the company believes could indicate potential issues. The company scans student emails before they’re delivered to their intended recipients, said Patterson, the CEO. Files within Google Drive, including Docs and Sheets, are scanned as students write in them, he said. In one instance, the technology led to the arrest of a 35-year-old Michigan man who tried to send pornography to an 11-year-old girl in New York, according to the company. Gaggle prevented the file from ever reaching its intended recipient.

Though the company allows school districts to alter the keyword dictionary to reflect local contexts, less than 5 percent of districts customize the filter, Patterson said.

That’s where potential problems could begin, said Sara Jordan, an expert on artificial intelligence and senior researcher at the Future of Privacy Forum in Washington. For example, language that students use to express suicidal ideation could vary between Manhattan and rural Appalachia, she said.

“We’re using the big scary algorithm term here when I don’t think it applies,” This is not Netflix’s recommendation engine. This is not Spotify.”

—Sara Jordan, AI expert and senior researcher, Future of Privacy Forum

On the other hand, she noted that false-positives are highly likely, especially when the system flags common swear words and fails to understand context.

“You’re going to get 25,000 emails saying that a student dropped an F-bomb in a chat,” she said. “What’s the utility of that? That seems pretty low.”

She said that Gaggle’s utility could be impaired because it doesn’t adjust to students’ behaviors over time, comparing it to Netflix, which recommends television shows based on users’ ever-evolving viewing patterns. “Something that doesn’t learn isn’t going to be accurate,” she said. For example, she said the program could be more useful if it learned to ignore the profane but harmless literary journal entries submitted to Dockter, the Connecticut student. Gaggle’s marketing materials appear to overhype the tool’s sophistication to schools, she said.

“We’re using the big scary algorithm term here when I don’t think it applies,” she said. “This is not Netflix’s recommendation engine. This is not Spotify. This is not American Airlines serving you specific forms of flights based on your previous searches and your location.”

“Artificial intelligence without human intelligence ain’t that smart.”

—Jeff Patterson, Gaggle founder and CEO

Patterson said Gaggle’s proprietary algorithm is updated regularly “to adjust to student behaviors over time and improve accuracy and speed.” The tool monitors “thousands of keywords, including misspellings, slang words, evolving trends and terminologies, all informed by insights gleaned over two decades of doing this work.”

Ultimately, the algorithm to identify keywords is used to “narrow down the haystack as much as possible,” Patterson said, and Gaggle content moderators review materials to gauge their risk levels.

“Artificial intelligence without human intelligence ain’t that smart,” he said.

In Minneapolis, officials denied that Gaggle infringes on students’ privacy and noted that the tool only operates within school-issued accounts. The district’s internet use policy states that students should “expect only limited privacy,” and that the misuse of school equipment could result in discipline and “civil or criminal liability.” District leaders have also cited compliance with the Clinton-era Children’s Internet Protection Act, which became law in 2000 and requires schools to monitor “the online activities of minors.”

Patterson suggested that teachers aren’t paying close enough attention to keep students safe on their own and “sometimes they forget that they’re mandated reporters.” On the Gaggle website, Patterson says he launched the company in 1999 to provide teachers with “an easy way to watch over their gaggle of students.” Legally, teachers are mandated to report suspected abuse and neglect, but Patterson broadens their sphere of responsibility and his company’s role in meeting it. As technology becomes a key facet of American education, Patterson said that schools “have a moral obligation to protect the kids on their digital playground.”

But Elizabeth Laird, the director of equity in civic technology at the Center for Democracy and Technology, argued the federal law was never intended to mandate student “tracking” through artificial intelligence. In fact, the statute includes a disclaimer stating it shouldn’t be “construed to require the tracking of internet use by any identifiable minor or adult user.” In a recent letter to federal lawmakers, her group urged the government to clarify the Children’s Internet Protection Act’s requirements and distinguish monitoring from tracking individual student behaviors.

Sen. Elizabeth Warren, a Democrat from Massachusetts, agrees. In recent letters to Gaggle and other education technology companies, Warren and other Democratic lawmakers said they’re concerned the tools “may extend beyond” the law’s intent “to surveil student activity or reinforce biases.” Around-the-clock surveillance, they wrote, demonstrates “a clear invasion of student privacy, particularly when students and families are unable to opt out.”

“Escalations and mischaracterizations of crises may have long-lasting and harmful effects on students’ mental health due to stigmatization and differential treatment following even a false report,” the senators wrote. “Flagging students as ‘high-risk’ may put them at risk of biased treatment from physicians and educators in the future. In other extreme cases, these tools can become analogous to predictive policing, which are notoriously biased against communities of color.”

A new kind of policing

Shortly after the school district piloted Gaggle for distance learning, education leaders were met with an awkward dilemma. Floyd’s murder at the hands of a Minneapolis police officer prompted Minneapolis Public Schools to sever its ties with the police department for school-based officers and replace them with district security officers who lack the authority to make arrests. Gaggle flags district security when it identifies student communications the company believes could be harmful.

Some critics have compared the surveillance tool to a new form of policing that, beyond broad efficacy concerns, could have a disparate impact on students of color, similar to traditional policing. Algorithms have long been found to suffer biases.

Matt Shaver, who taught at a Minneapolis elementary school during the pandemic but no longer works for the district, said he was concerned that racial bias could be baked into Gaggle’s algorithm. Absent adequate context or nuance, he worried the tool could lead to misunderstandings.

Data obtained by The 74 offer a limited window into Gaggle’s potential effects on different student populations. Though the district withheld many details in the nearly 1,300 incident reports, just over 100 identified the campuses where the involved students attended school. An analysis of those reports failed to identify racial discrepancies. Specifically, Gaggle was about as likely to issue incident reports in schools where children of color were the majority as it was at campuses where most children were white. It remains possible that students of color in predominantly white schools may have been disproportionately flagged by Gaggle or faced disproportionate punishment once identified. Broadly speaking, Black students are far more likely to be suspended or arrested at school than their white classmates, according to federal education data.

Gaggle and Minneapolis district leaders acknowledged that students’ digital communications are forwarded to police in rare circumstances. The Minneapolis district’s internet use policy explains that educators could contact the police if students use technology to break the law and a document given to teachers about the district’s Gaggle contract further highlights the possibility of law enforcement involvement.

Jason Matlock, the Minneapolis district’s director of emergency management, safety and security, said that law enforcement is not a “regular partner,” when responding to incidents flagged by Gaggle. It doesn’t deploy Gaggle to get kids into trouble, he said, but to get them help. He said the district has interacted with law enforcement about student materials flagged by Gaggle on several occasions, but only in cases related to child pornography. Such cases, he said, often involve students sharing explicit photographs of themselves. During a six-month period from March to September 2020, Gaggle flagged Minneapolis students more than 120 times for incidents related to child pornography, according to records obtained by The 74.

Jason Matlock, the director of emergency management, safety and security at the Minneapolis school district, discusses the decision to partner with Gaggle as students moved to remote learning during the pandemic. (Screenshot)

“Even if a kid has put out an image of themselves, no one is trying to track them down to charge them or to do anything negative to them,” Matlock said, though it’s unclear if any students have faced legal consequences. “It’s the question as to why they’re doing it,” and to raise the issue with their parents.

Gaggle’s keywords could also have a disproportionate impact on LGBTQ children. In three-dozen incident reports, Gaggle flagged keywords related to sexual orientation including “gay, and “lesbian.” On at least one occasion, school officials outed an LGBTQ student to their parents, according to a Minneapolis high school student newspaper article.

Logsdon-Wallace, the 13-year-old student, called the incident “disgusting and horribly messed up.”

“They have gay flagged to stop people from looking at porn, but one, that is going to be mostly targeting people who are looking for gay porn and two, it’s going to be false-positive because they are acting as if the word gay is inherently sexual,” he said. “When people are just talking about being gay, anything they’re writing would be flagged.”

The service could also have a heavier presence in the lives of low-income families, he added, who may end up being more surveilled than their affluent peers. Logsdon-Wallace said he knows students who rely on school devices for personal uses because they lack technology of their own. Among the 1,300 Minneapolis incidents contained in The 74’s data, only about a quarter were reported to district officials on school days between 8 a.m. and 4 p.m.

“That’s definitely really messed up, especially when the school is like ‘Oh no, no, no, please keep these Chromebooks over the summer,’” an invitation that gave students “the go-ahead to use them” for personal reasons, he said.

“Especially when it’s during a pandemic when you can’t really go anywhere and the only way to talk to your friends is through the internet.”