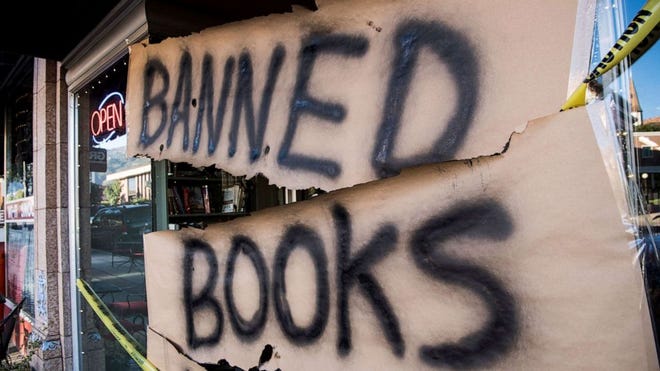

Florida has the second highest number of school-related book bans in the country, according to an analysis published last week by PEN America, a free speech and literary organization.

There are 566 book bans within 21 Florida school districts, according to the analysis. Texas was the only state with more bans at 801 across 22 districts.

Jonathan Friedman, report author and PEN America’s director of free expression and education programs, said in a Sept. 19 briefing the trends show book bans are a targeted effort.

“These are not just individual complaints about books that parents are complaining about because their children are bringing them home,” Friedman said. “Overwhelmingly, we are seeing people Google ‘what books have LGBTQ content whatsoever,’ even just a book that has an illustration of a same-sex interracial couple gets thrown onto one of these lists and ends up banned in some districts in Florida.”

Over the past year or so, books were banned at least 2,500 times by more than 130 school districts across 30-plus states, according to the analysis.

PEN America:Here are the 411 books banned in Florida school libraries and classrooms

Book Bans:List of books challenged in schools tracked by Florida Freedom to Read Project

And:PEN America: Here are the 30 books banned in Lee County Schools libraries and classrooms

The unprecedented trend escalated throughout the spring and into the summer, according to PEN, which in the spring published a preliminary report documenting 1,586 book bans nationwide during the nine months starting in July 2021.

“‘More’ is the operative word for this report,” PEN writes, comparing the latest analysis to the preliminary one. “More books banned. More districts. More states. More students losing access to literature.”

The trend’s proponents have also gotten more savvy – and more creative – in their book challenging strategies.

“Over the 2021-22 school year, what started as modest school-level activity to challenge and remove books in schools grew into a full-fledged social and political movement,” PEN writes. That movement, according to PEN, has been powered by at least 50 activist groups as well as politicians who have pressured or chilled schools into restricting children’s access to certain books.

When did the current wave of book challenges start?

Take a look:Schools banned books 2,532 times since 2021. It’s all part of a ‘full-fledged’ movement.

Also:Sanibel Public Library draws some parents’ ire for Pride Month book display

Book bans:Here are the 5 Pride Month books challenged at the Sanibel Public Library

PEN describes the recent spate of efforts to restrict books as an “evolving censorship movement.” While the tensions leading up to it had been percolating for a while, the current trend can be traced back in part to last year.

More than two dozen states already had begun considering — and in some cases passing — legislation to restrict discussions about race, sexual orientation and gender identity in classrooms. The legislative efforts were fueled by Republican resistance to so-called “critical race theory,” a graduate-level legal concept that examines how racism continues to permeate policy and society. The critical race theory backlash morphed into a broader push to eschew conversations about LGBTQ+ issues from classrooms.

The wave picked up momentum last fall when activists and conservative policymakers intent on reforming curricula began focusing much of their energy on books.

In Florida, many of the bans have been accelerated by the passing of new laws that have emboldened parents and community members to speak out against library materials.

On March 25, Gov. Ron DeSantis approved House Bill 1467, which gives parents and members of the public increased access to the process of selecting and removing school library books and instructional materials.

On March 28, DeSantis signed the Parental Rights in Education bill, dubbed the “Don’t Say Gay” bill by critics, that prohibits school instruction of sexual orientation and gender identity in kindergarten through third grade.

In anticipation of the new laws, the Palm Beach School District pulled and reviewed 31 books in addition to other learning materials to make sure they were complying with the new laws. While the dozens of books made it back onto library shelves, those that mainly focused on gender identity or sexual orientation are now restricted to grades four and above.

Chaz Stephens, a Deerfield Beach resident who said he is an archbishop with the First Church of Mars, sent a request to ban the Bible from 62 Florida school districts in response to HB 1467.

Who’s trying to ban books?

Large majorities of Americans oppose book bans — at least 70% of both Democrats and Republicans, according to one poll. So why have so many books been removed from schools and libraries?

PEN attributes the movement largely to the dozens of groups — many self-described as “parents’ rights” organizations — that have often disseminated lists of books they argue aren’t appropriate for schoolchildren and have mobilized members to testify at school board meetings.

At the forefront of these efforts are eight organizations that altogether comprise 300 or more local or regional chapters, according to the PEN analysis. These national groups include Moms for Liberty, US Parents Involved in Education, No Left Turn in Education and Parents’ Rights in Education.

In Florida the two most notable groups are Moms for Liberty and Florida Citizens Alliance, a nonprofit that aims to improve education for children by empowering teachers, students and parents.

The alliance has compiled a list of 58 books in Florida’s school libraries they deem “pornographic” and has called on Florida’s school districts to remove them. The group also pushes for the elimination of sex education in K-12 schools.

“A teacher can’t give a child an aspirin without the parent’s permission yet we can give them this smut and encourage them to be sexually active,” said Keith Flaugh, co-founder of the alliance. “The obscenity statutes are pretty clear that this material is in violation of Florida obscenity statutes for minors.”

The alliance is responsible for bans in school districts in Jackson, Orange, St. Lucie, Polk and Walton counties, according to PEN America.

It also is responsible for advisory labels placed on 115 books in the Collier County School District that contain LGBTQ+ characters, transgender characters, characters of color and sexual content.

Flaugh said the word “ban” is misleading and prefers the word “prohibit” be used instead.

“It’s an incendiary word that doesn’t represent what we’re talking about,” Flaugh said. “We’re talking about protecting the innocence of children and safety. This is really about protecting our children and keeping the harmful materials from them just like we do drugs and cigarettes.”

Also:Here are the 115 library books Collier County Schools placed an advisory label on

While PEN America doesn’t classify the advisory labels as a book ban, they included them in its report.

“These types of actions could have a chilling effect — applying a stigma to the books in question and the topics they cover — and they merit further study.” the report stated.

While Flaugh said he’s glad that school districts in Florida are working on how to “protect children” from books with what he said is obscene material, he added that most of the districts aren’t going far enough.

“We’ll be continuing to work in the legislative cycle to get some additional teeth in that,” Flaugh said.

All in all, the “parents’ rights” groups, most of which have formed since 2021, played a role in at least half of the book bans last school year nationwide. (PEN defines a book ban as any action taken against a book that — resulting from community requests, administrative decisions or legislation targeting its content — leads to it being removed or otherwise restricted.)

And, according to PEN, these groups have developed new tactics for restricting book access. For example, some have taken to scrutinizing and interfering in district book purchases or digital library apps.

In some cases individual community members who do not have children in public schools are placing complaints to school districts. One of those Florida residents is 69-year-old Dale Galiano who submitted all of the St. Lucie County School district’s 17 book challenges in the 2021-22 school year.

Lawmakers and other politicians are also helping to drive the challenges through legislation or policy change that somehow implicates books. According to PEN, roughly 40% of the bans documented during the 2021-22 school year “are connected to political pressure exerted by state officials or elected lawmakers.”

“The unprecedented number of challenges we’re seeing already this year reflects coordinated, national efforts to silence marginalized or historically underrepresented voices and deprive all of us — young people, in particular — of the chance to explore a world beyond the confines of personal experience,” said Lessa Kananiʻopua Pelayo-Lozada, president of the American Library Association.

Which books are being banned?

Between July 1, 2021, and June 30, 2022, according to PEN, 411 titles had been banned from school libraries and classrooms in Florida.

Nationwide, 2,532 book bans were enacted, affecting 1,648 individual titles. (Many titles were banned by more than one district.) Most of the bans involved books that were indefinitely or temporarily removed from shelves pending investigations or reviews.

The ALA on Friday published a separate preliminary analysis documenting attempts to ban or restrict library resources between Jan. 1 and Aug. 31, 2022. Seventy percent of the 681 attempts documented during that period targeted books also listed in PEN America’s report, the analysis found.

Books that are by authors of color, deal with racism and/or feature LGBTQ+ relationships are overrepresented on the lists. Many are graphic novels.

Supporters of book bans often argue the titles they are challenging are too obscene or mature for young readers. The most targeted title, by far, is Maia Kobabe’s graphic novel, “Gender Queer: A Memoir,” which was banned in 41 school districts nationwide, including four in Florida this past year.

George M. Johnson’s “All Boys Aren’t Blue” comes in second place, banned in 29 districts, including six in Florida. Also on the list: “Out of Darkness” by Ashley Hope Pérez (24, three of which are in Florida); “The Bluest Eye” by Toni Morrison (22, including seven in Florida); “The Hate U Give” by Angie Thomas (17, including eight in Florida); “Lawn Boy” by Jonathan Evison (17, including one in Florida); and “The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian” by Sherman Alexie (16, including six in Florida.)

The most targeted books in Florida are “Thirteen Reasons Why” by Jay Asher and “The Hate You Give” by Angie Thomas, both of which have eight bans.

In Flagler County, the book “All Boys Aren’t Blue,” a memoir of a Black LGBTQ activist by George M. Johnson, was taken off shelves after a school board member filed a police report because the district was taking too long to review her initial concern about the book’s content.

Duval Public Schools decided in August not to distribute books ordered from the “Essential Voices” classroom library collection, which offers a wide range of age-appropriate, inclusive books for use in school. The books were flagged due to concern for their content.

Books included in the 176 book collection include “Fry Bread: A Native American Family Story” by Kevin Noble Maillard, “Dim Sum for Everyone” by Grace Lin, and “Pink Is For Boys” by Robb Perlman. The books are reportedly sitting in a warehouse.

In Brevard County, the district banned teachers from using Epic, a library system boasting about 40,000 titles for young readers, and Prodigy, an online game in which students play as wizards engaging in math battles, because it did not have the capability to properly vet the websites per Florida legislation passed this spring regulating how schools choose instructional material.

The Walton County School District removed 24 books from its libraries based off the list of books sent to them by the Florida Citizen’s Alliance. The superintendent removed the books despite not having read any of the books in question.

“We are clear that those who are advocating on this issue are within their rights — freedom of assembly, mobilization, using their voices. That’s perfectly appropriate,” Suzanne Nossel, CEO of PEN America said last week. “But when the end goal is censorship, as a free expression organization, it’s our obligation to call that out and to point out that even the use of legitimate tactics of expression can sometimes lead to a censorious and speech-defeating result.”

Contact Alia Wong at (202) 507-2256 or awong@usatoday.com. Follow her on Twitter at @aliaemily.

Nikki Ross covers education for the Fort Myers News-Press and Naples Daily News. She can be reached at NRoss@gannett.com, follow her on Twitter @nikkiinreallife, Instagram @reporternikkiinreallife or TikTok @nikki.inreallife.