This weekend marks Houston’s pride festival, as anyone driving through Montrose will instantly affirm. The big march has been postponed till September, another consequence of the pandemic, but Houston’s queer nation — in all its varied and sometimes confusingly complex expressions — will have no shortage of opportunities to flirt and frolic and fly its many-hued flags.

This season of celebration arrives at a pivotal time for Houston, as we finally emerge from the 15-month lockdown that left so many on edge. It also comes as the city and most of America continues to work out profound tensions exposed by the disproportionately high number of COVID deaths among Latino communities, the killings of Black Americans including George Floyd and Breonna Taylor and the simmering sense of danger felt by too many Asian Americans.

Many of us are also still tallying personal losses, too. It’s been nine months since my father died, for instance, and my world hasn’t quite rebalanced itself, even as it continues to be rocked by my partner’s struggle with illness, and increasingly, new and unsubtle reminders of my own mortality.

None of those things is unique to me or even to the pandemic, which has claimed over 600,000 lives in America. Death and disease and aging attend any life, in any era and in any place. But as I drive the streets of my adopted city of Houston this summer and look upon the bright colors of the Pride banners waving in the sun, I sense support of a kind that I’ve rarely before bothered to acknowledge. Maybe I felt I did not need that strength, not since I came out as a young adult so long ago. Now, I find myself freshly 50 and soaking up all the affirmation I can get as I sail into the uncharted territory of middle-aged vulnerability.

The strength is not flowing from the raucous parties I know are happening in some corners of the city this weekend. Nor is it emanating from the obvious and refreshing ease with which so many LGBTQ+ people have with their sexuality these days — a near miracle for any who knew the terror-bit terrain of earlier eras.

My anchor during this uncertain summer has been the reminders of a secret and fading geography of gay Houston peaking out from maps, from faded signs and on plain-looking street corners that more and more Houstonians forget ever existed. The signposts of an earlier era are receding from our visual landscape as society becomes a place where gay people can be themselves wherever they are. But if you know where to look, they yet tell a story all Houston should be proud of, for here, in one of America’s great cities, thousands of gay people just like me only braver, forged lives of dignity and optimism across many decades, and did so before it was safe to even reveal one’s true colors, much less wave a banner proclaiming pride in them.

When I marvel at the progress gay rights have made in just my lifetime, and when I shudder at the challenges many in the LGBTQ+ community still face, I think of an ordinary corner in east downtown Houston. There, at 2400 Capitol near the intersection with Emancipation, a young man pulled over to the side of the street 41 years ago this weekend. The Friday night parties of Pride weekend had been underway for hours by the time he had gotten off work at the bus depot three blocks over at 1:45 a.m. As he passed a lot near a warehouse, he slowed his car to talk to two men wearing blue slacks and white T-shirts.

Fred Paez was 27 and a former University of Houston student journalist who had come out to himself while covering the local gay activism scene and then dove in to emerge as one of the community’s most visible leaders. His decision to get out and talk to K.M. McCoy, 26, and S.A. Cain was among the last he ever made, as McCoy shot him through the back of the head at roughly 2:30 that morning. He died instantly, temporarily galvanizing Houston’s gay community and making headlines nationwide.

Later that morning, the Houston Police Department explained that the two men were off-duty police officers, with McCoy working overnight security for Best Delivery Service and Cain simply a friend who had stopped by for a late-night visit. Between the two of them they had consumed 12 beers before Paez slowed down to say hello, testimony at trial would later reveal. The report said Paez had suggested that the three walk around to the side of the building. When they arrived, according to police, Paez reached out and touched McCoy between the legs.

McCoy pulled out his ID and pushed Paez up against a nearby car. “Officers had intended to arrest this subject and charge him with public lewdness,” the police report said. But according to police Paez struggled and in the melee, the loaded .45 automatic pistol McCoy had been holding to the back of his head accidentally discharged.

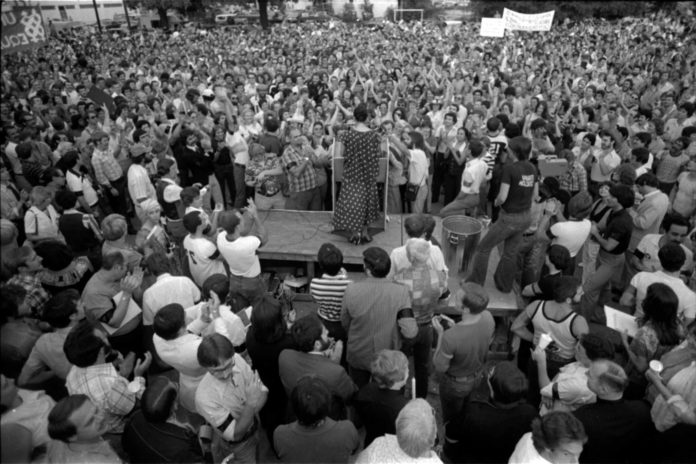

The killing triggered protests at least a thousand-strong in Houston, where police had a history of raiding gay bars and busting gays for what often felt like entrapment. A task force was formed. Members of Congress demanded answers. An annual march took place for a couple years. And McCoy was indicted and tried — but on a misdemeanor charge, and acquitted. Though most of the reaction eventually fizzled, it laid seeds for stronger reforms 11 years later.

Paez’s friend Ray Hill delivered a eulogy that has echoed in my head since reading its words. Hill said he wasn’t mourning his young friend, whom his Baptist faith told him was already in heaven. “What I worry about are those of us that have waiting somewhere in destiny our own dark alley — have waiting somewhere in our destiny our own cocked forty-five automatic,” he told fellow mourners. He urged them to find peace amid the fear and to use Paez’s courage as a model. “I hope that you come to know the personal joy of being excited about who you are and what you are doing. And I leave you with the certain knowledge Fred Paez enjoyed those things,” Hill said.

I’ve been thinking about what extraordinary qualities a man of 27 had to have in 1980 to lead the kind of life Hill spoke of. In 1980, gay men and women had to earn that happiness step by step, by recreating families where their old one insisted on hate. By constructing places to gather in a world where they were still regarded as criminals. By forging ties to one another to create safe networks where it was possible to live free of fear. In 1980, the queer community would still have another 23 years before the Supreme Court ruled they were not de facto criminals, no matter what Texas lawmakers said. Gay marriage, gay adoption, open service in the military, freedom from the constant threat of personal violence — something that to this day haunts too many, especially transgender women — were all still decades or more away.

I was only 9 when Paez was shot to death. But by his courage and by others’ the world I inherited as a teenager had begun to change, even if very slowly in most parts of America. By the time I was 20 in college in Kentucky, another young man of 27 died on the streets of Houston — only this time, the city was ready to respond.

On the morning of July 4, 1991, Paul Broussard was leaving the clubs on Montrose with two friends when a car stopped in the 1000 block of West Drew to ask directions. Then the doors swung open — and from a second car, too — and 10 youths from The Woodlands, ages 17 to 22, spilled out with bats and knives. Earlier in the evening, they had gathered at an intersection not far from where I live now — Washington and Studewood.Of the three who were attacked, one escaped, another was hospitalized and released and Broussard was stabbed in the chest and back and did not survive.

It took the police a couple of weeks, but they soon called the crime what it was — a gay bashing. All 10 youths were indicted on charges that included several counts of murder or attempted murder. Houston City Council passed a hate crimes ordinance. Broussard was memorialized in Rothko Chapel, and to this day the location of Broussard’s murder is seen as a landmark in the city’s long march toward safety and acceptance for its LGBTQ+ community. Five of the 10 attackers were sentenced to prison, including Jon Buice, then 17, who turned himself in, pleaded guilty and accepted a 45-year sentence. The other five were given probation.

The history of gay people in Houston and the community they’ve built, often in restaurants, bars and bookstores, but also among street protests and planning rooms and shared struggles, has created a geography of gay civil rights that has begun to fade as LGBTQ+ people more than ever before are able to be themselves wherever they are. Here are seven landmarks in that history that together help tell that story.

1936. Wagon Wheel night club outside of Houston on Airline and Little York, on the road to Dallas. Local historians say in all likelihood, this early club catered to straight men looking for a wild time, rather than as a place where men could meet each other. But it heavily promoted its star attraction – a widely heralded troupe of female impersonators – and eventually drew the determined scrutiny of the grand jury, despite the sheriff’s insistence at the time that no law existed that the shows, purposely staged outside of city limits, violated. It burned in 1938, with inspectors blaming arson.

1945. Opening of the Pink Elephant at the corner of Fannin and Bell Streets. Prior to the opening of this bar, which we’d recognize today as a gay bar, men and women who wanted to meet each other for sex or socialization had to take their chances at an elaborate network of coded places, such as lobbies in downtown hotels such as the Rasthskeller and Rice Hotel where they could subtly indicate their availability, essentially hiding in plain sight.

1976. The Exile, 1011 BellStreet.Houston had its first Pride parade in June of the Bicentennial year, six years after New York City’s inaugural parade in 1970. As former Houston Mayor Annise Parker told me this week: “I was there. Not really a parade and a rather short march!” But it was a start. When funding ran dry the next year there was no second march, not yet anyway.

June 16, 1977. Hyatt Regency Hotel. The Texas Bar Association had invited country and western star Anita Bryant to perform at its convention in Houston. Bryant was an indefatigable campaigner against gay rights and loathed among the community. Earlier that day outside of City Hall, speakers led a crowd of 300 through a call-and-response denunciation of homosexuality. Three thousand gays and allies marched in a candle-light procession that night to the Hyatt. In many ways, this was the galvanizing moment for large-scale gay rights protests in Houston.

June 28, 1980. 2400 Capitol Street in east downtown. Houston gay activist Fred Paez is killed by an off-duty police officer who attempted to arrest him for public lewdness, after Paez reportedly hit on the officer outside a warehouse where the officer was working a second shift security job. He was tried on a misdemeanor charge and found not guilty.

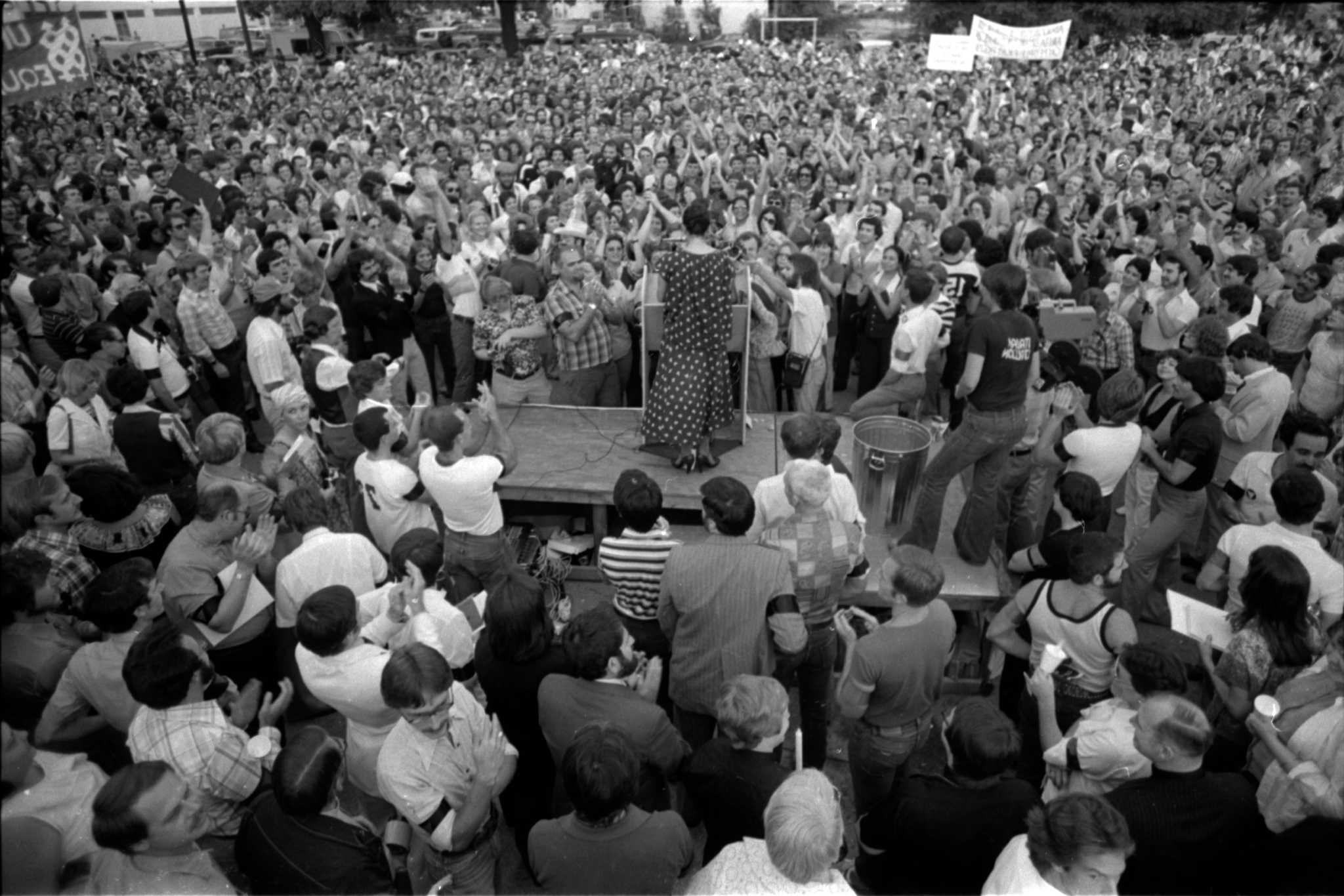

Westheimer and Montrose, July 14, 1991. One thousand-plus people gather in a takeover of the intersection organized by the national gay rights group Queer Nation in protest of the brutal murder of Paul Broussard by a group of 10 young people who had driven to Montrose from the Woodlands and jumped Broussard and two friends as they left a gay bar early on the morning of July 4.

Sept. 17, 1988. Colorado Club Apartments, # 833, in far east Houston. A jealous lover calls the police on John Lawrence and Tyron Garner. When they respond, they cite the couple for having sex in their apartment. The case goes all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, which in June 2003 issues a sweeping decision striking down any laws that make private sex between members of the same sex illegal.

Sources: Much credit goes to Brian Reidel and Joanna Collier for help in pointing me to original sources for these and other events, and to J.D. Doyle, whose massive online collection of gay history artifacts is a treasure.

These two deaths are part of a Houston history that isn’t often retold, except perhaps in the recollections of those who lived through it. I share it now because I’ve found it helpful to be reminded of the struggle — the pain, the protest, the courage as well as the laughter and tears — of those who have come before me to forge a city where I am free to live a life of peace. All over Houston there are invisible markers where people lived and laughed and sometimes died to build the city we know. We ought to remember those places, and the people who made them memorable, as key sources of strength in our own still-unfolding journeys. As my life this past year has reminded me, there is no freedom from fear — there will be pain and loss and grief for all of us — but we can be free of the fear of one’s self, or of love, or of how others may see us. That was Ray Hill’s wish for all of us 41 years ago after Fred Paez died, and it’s the future people such a Fred helped make possible.

Lindenberger is the deputy opinion editor for the Houston Chronicle. His email is michael.lindenberger@chron.com.