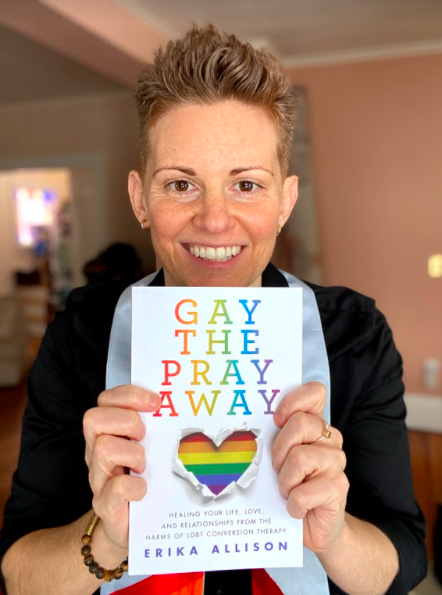

GREAT BARRINGTON — Rainbow flags flutter in earnest at this time of year, and for good reason. June marks the start of LGBTQ Pride month — to commemorate the 1969 Stonewall Riots in the United States and to celebrate the impact of LGBTQ+ people around the world. Pride, the apt antithesis of shame and stigma, is a month-long opportunity to promote the dignity, equality, rights, and increased visibility of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer people. In the Berkshires, local author Rev. Erika Allison is leading the charge with her new book, “Gay the Pray Away: Healing Your Life, Love, and Relationships from the Harms of LGBT Conversion Therapy” (Difference Press, 2021).

In her book, the title of which is a tongue-in-cheek play on the conversion-therapy phrase “pray the gay away,” Allison shares her story of healing and offers a path to live “gayly ever after” for others who have experienced identity rejection. When looking for a way to tell her story, one that showed her overcoming a decades’ old experience, Allison leaned on this play on words to create the opposite effect: “Instead of trying to pray this part out of me, I let my gay self out and shined it so brightly that I gayed away all those attempts to change who I was,” she told The Edge in a recent interview. Which, in a world rife with labels, is a way of reclaiming her power, with a twist.

Allison, a newly-ordained interfaith minister, grew up in a “suburban community between Dallas and Ft. Worth, [where] the question wasn’t whether you went to church or not; it was which one you attended. The norms were very well-established,” she writes in the opening pages of her book. Her parents pined for their daughter to have a life that was easy and happy — the assumption being that if she were gay, she would miss out on these things. Suffice it to say, Allison is doing the hard work of bringing marginalized experiences to light and making them more prominent — a process that has required “peeling back the layers a little bit deeper” and tons of healing.

“I had to get to a particular point in my own development where I could stop putting [my parents] on that pedestal of having all the answers, of knowing everything that’s right, and needing their approval, [and begin stepping] into my own sovereignty and authority over my life.” Her book calls for consciousness, a process she explains as beginning with intention, “not meaning to do any harm— but that is not going to get us all the way there. The next step is looking closely at how intentions play out in the world,” namely how they create blind spots, then stepping back “to look outside the narrow view of things and take responsibility for the bigger picture outcome — not just the intention.” In her work as an author, speaker, coach, and minister, her remedy is to “Listen deeply, from a place of quiet and stillness, to what my heart and soul says is true.”

Hannah Van Sickle: Can you help define conversion therapy, or put the practice into context, for readers who are unfamiliar?

Erika Allison: There is an overarching term, called Sexual Orientation Change Efforts, [under which conversion “therapy” falls]. It’s a type of practice with the goal of changing [the sexual orientation of homosexual and bisexual individuals to heterosexual] and now gender identity has come under that umbrella, as well. Typically, [conversion therapy] is conducted through a religious lens — and tends to be motivated through religion, but not exclusively — and is based on the premise that being gay is out of alignment with God’s plan for your life, and therefore the best way to save someone’s soul is to change them. It is based on the [erroneous] premise that sexual orientation can be altered or changed, because it is a choice of some kind, not a fixed part of oneself.

HVS: When writing this book, who was your intended audience?

HVS: When writing this book, who was your intended audience?

EA: If I had to draw a circle, the smallest circle of my target audience would be people who are LGBTQ who — to make the circle even smaller — have experienced some kind of wounding from their religious past. I knew I needed to come from my grounding, which was in my own experience, but I’ve had so many people read it and say this isn’t just for people who have been through conversion therapy. There is so much here for anyone who has been through any kind of experience where someone, society, or some messaging told them who they are is not okay. And that causes harm, any way you look at it. It tends to be that, if we don’t do something to overwrite those deeply programmed messages, they will follow us throughout life.

HVS: What is your stance on labels when it comes to the conversation surrounding sexual orientation/gender identity?

EA: Labels continue to morph and change. When all this happened in my life 20+ years ago, the word queer was not being used — [LGBTQ individuals] didn’t want to be identified as that — now queer tends to be this over-encompassing term for anyone who is not in the heteronormative mainstream. Labels are interesting. They can be helpful and they can be harmful. I think the key is: Does the individual get to identify their own labels or are they being [assigned] by someone from the outside? It’s helpful for me to identify as LGBTQ, in some cases, because I don’t have the same experience as [others]. I did receive some sort of marginalized treatment because of who I am in the world, and if I erase that label — and I don’t name that as part of my experience — there is a risk of my erasing the experience itself, and there is a lot of strength, a lot of growth, a lot of gold in that experience. [Today], things are becoming more open and more fluid. I think when we use labels, and it’s welcome by an individual, to create a system of belonging — and to help others see that where I am coming from has required overcoming some things — it is very helpful. [Labels] are not helpful when they take away our ability to be fluid, and to be who we are at any moment, knowing that we are all changing and labels are not needed to exist.

HVS: How do we work to remedy (and hopefully eliminate) the hurdle of “coming out” that does not exist for individuals who identify as heterosexual?

EA: I think the time of coming out may be slowly going away — and there will be less and less need for that over time — but I don’t think we are quite there yet. I still think where most of this comes from, unfortunately, is religion-based conditioning. Take my parents, for instance: everything they did was motivated by love. That’s what makes this so complicated; it’s one of the few types of abuse where love is the cause, and it was almost that my Mom loved me so much that she wanted my soul to go to heaven with her. Whatever she had to do [to reach that goal] she would do, [and] what that looked like was some pretty extreme [measures] to save me from this “thing” that had a hold over me. No one should have to come out: we should all just be who we are and it should be fine. I think we are getting to that point.

HVS: What inspired you to become an interfaith minister, and what keeps you motivated in your work?

EA: Typically, our religious institutions have excluded the LGBTQ population and, even the ones who are considered accepting, it often feels — from the perspective of someone in this community — like [LGBTQ individuals] are being reluctantly included, which is very different from feeling truly celebrated. That is one of my goals as an interfaith minister: to help people heal from that religious trauma without having to leave spirituality completely. A research study out of Australia, that was just released in March, basically found that people who had religious harm, like conversion therapy, who then went to traditional psychotherapy, in most cases [were told] they needed to leave the religion completely in order to find healing. It’s the same concept as leaving an abuser — you can’t stay in an abusive relationship [and heal] — but what they found is that it was causing further harm to LGBTQ people. They didn’t want to have to make the decision to completely leave religion, faith, spirituality. So part of my goal as an interfaith minister is to help people find a place in their spiritual world where [all of this] can coexist, to broaden their view of spiritually such that who they are is completely validated. They don’t have to throw that part of themselves away, they can actually have their spirituality in a way that affirms and celebrates who they are.

My active ministry is trying to create a monthly, spiritual gathering and community, called Gay the Pray (next meeting June 6 at 8 p.m.), where LGBTQ individuals feel like they can dive in and explore spirituality knowing, from the outset, that who they are is completely accepted and celebrated. It’s spiritual, not religious, [aimed at] helping people find their spiritual center, that place within themselves that is connected to source, higher self, universe — specifically for LGBTQ individuals to find others who are on that path. You can be queer and not run into many people who are thinking spiritually, and you can be in spiritual circles and not run into many people who are queer. And I’m attempting to bring those worlds together [by] finding that harmony between spirituality and sexuality.

HVS: What kernel of wisdom have you learned from your journey to date that you would share with young people today struggling with similar obstacles that you faced?

EA: I would love for the learning curve not to be as long as mine was. I would love for people who have received any kind of negative messaging, or any kind of programmed experience that somehow leads to them feeling flawed or not lovable or not worthy … to read this book and realize they are carrying that now, and do the unpacking and the reprogramming of that now, rather than having to carry around the residuals of those messages for 20 years. This is [also] what keeps me motivated: when I look at my life story, it really took me about 20 years to unpack the fact that I was still carrying around wounding from my experience. I often said [in regards to conversion therapy] “no harm no foul;” it didn’t work, it didn’t make me not gay, so it must not have harmed me either — it must have been a neutral experience. That was a fine belief for a while, and [likely] kept me alive. Interestingly, as I got older and continued through my life, and I watched myself sabotage relationships or I watched myself hop around from career to career still searching for something, I really had to draw a connection between all these things happening and that first experience [with conversion therapy].

HVS: Is there a role for allies in this process?

EA: There is always a role for allies. Allies have been critical along this entire path for LGBTQ rights and equality. I was living in Maine back when gay marriage was being voted into the world, and I remember the first time it was on the ballot, we lost. The second time it came on the ballot, we won. Some of my friends who were leaders in the movement said the key difference was that allies got involved the second time around. The people who have the power also have the ability to create influence—they can change systems and create environments that work better for all people — if they are aware and awake in those positions of power and privilege.

What allies have the opportunity to do is to offer a completely affirming, loving, celebratory presence to anyone in the LGBTQ community, and continue to let that person know they are loved exactly as they are. Don’t underestimate the power of offering that level of acceptance to someone. [In a world full of] subtle messages of non-acceptance … one individual can make a difference by sharing a message of “I totally love and accept you as you are.”

Note: You can find “Gay the Pray Away” at The Bookloft in Great Barrington, The Bookstore in Lenox, and on Amazon. The audiobook version, produced by Alison Larkin Presents, can be found here.