If you’re hoping for passenger rail service out of Knoxville any time soon, you’re in for a long wait.

Making it happen would take decades and Knoxville hasn’t really started yet. And the challenges are steep, from tracks to topography to a lack of political interest in trains.

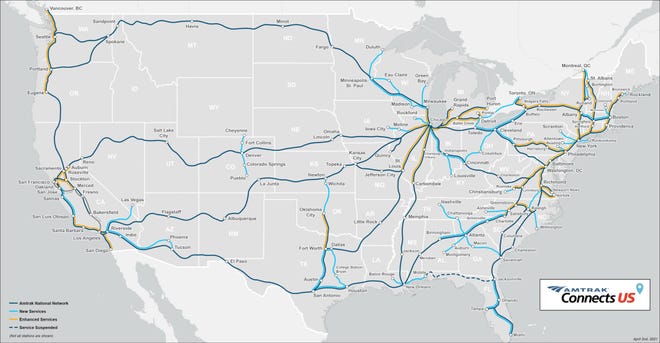

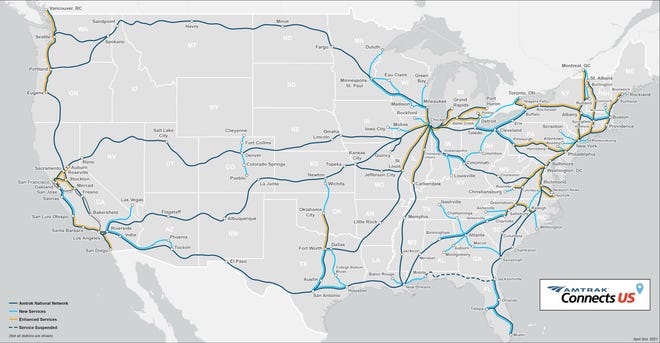

All of those hurdles explain why Knoxville was left out of President Joe Biden’s $80 billion infrastructure plan, which included significant Amtrak service extensions to make rail a real option for millions of Americans.

Knoxville will be the only major Tennessee city without passenger rail service if the project advances. It proposes service expansions by 2035 to Nashville and Chattanooga, as well as Asheville, North Carolina, as well as major expansions throughout the rest of the nation.

Knoxville, meanwhile, lacks a champion pushing for service, and private freight railway companies don’t want to share their tracks with passengers.

But some experts say there’s room on the rails, and if neighboring cities like Bristol or Chattanooga get passenger service, extending that to Knoxville would be possible.

Both Amtrak and the Tennessee Association of Railway Passengers said that if service started to nearby cities it could very well extend to Knoxville, but it would happen faster with strong local support.

“Knoxville is an enormous market,” said Jarod Pearson, president of the Tennessee Association of Railroad Passengers. “There would never be a scenario where a passenger train would pass through Knoxville without stopping.

“It can certainly be done if the city and county get involved.”

What’s stopping expansion to Knoxville?

Pearson said that the primary obstacle to getting passenger service in Tennessee has been a lack of local and state interest and coordination.

“When it comes time to talk about funding and coordination, that’s when the conversation gets tabled,” Pearson said, “We’re just not there in Tennessee. We have not gone far enough.”

That’s also the case in Knoxville.

The Knoxville Regional Transit Corridor Study, which looked for places to improve local rapid transit in Anderson, Blount and Knox counties, focused on road-based solutions, recommending, for instance, improving bus transit by speeding up buses, using bus-only lanes and giving them priority at intersections.

The Tennessee State Rail Plan, meanwhile, does not identify Knoxville as a potential target of intercity passenger rail service expansion.

Tennessee Department of Transportation Freight and Logistics Director Daniel Pallme said in email that he was not aware of any passenger rail studies done on Knoxville.

“An Amtrak connection isn’t an issue that’s been raised much in community discussions so far, so there’s no good gauge right now on community interest,” said Knoxville spokesperson Eric Vreeland. “But the White House’s proposed federal infrastructure investment and how it could upgrade Amtrak service may very well generate more discussion locally.”

In 2018, advocates proposed a light rail in Knoxville, but track owners opposed it and no other proposals have surfaced since then.

The rail that runs through Knoxville is owned by CSX and Norfolk Southern, which use it to move freight. Both companies have been historically hesitant to allow passenger trains to share their rails.

“There are a lot of downsides and little to gain for them. They want zero interference with freight operations if passenger service is permitted,” said David Clarke, retired director of the University of Tennessee Center for Transportation Research.

Clarke said that to share tracks, private rail companies typically demand that additional infrastructure be built so that passenger trains do not interfere with freight trains. This can mean things like improved signals, or sidetracks that let trains using the same track in opposite directions go around each other.

But there could be some capacity for passenger trains on the existing freight rail system. Locally, freight rail primarily moves coal, especially to power plants. As coal use declines that could free up capacity on the system, possibly for passengers.

“Does that create capacity for passenger rail? The answer is yes, yes, yes.” said Amtrak spokesperson Marc Magliari. “If there are (local) capacity issues they can be addressed. None of this is undoable.”

What are the physical limitations?

There are other challenges, beyond administrative ones.

Portions of the old Central Tennessee Railway track that linked Nashville and Knoxville over the Cumberland Plateau were abandoned between 1980s and 1990s, which makes restoring direct service more costly.

In all likelihood a Knoxville-Nashville line would connect through Chattanooga, which means a longer trip by rail than by car and a tough sell for the average traveler.

Clarke said many of the existing tracks are curved and twisted due to the often extreme topography of the region, making high-speed service less feasible and practical. Local trains might be limited to between 60 and 80 miles an hour.

“It’s a pretty slow trip from Asheville to Knoxville by train because the train goes along the French Broad River,” said Clarke, “It’s like a little over an hour and a half by car. By train it’s probably more like two and a half hours.”

Clarke said that to make truly high-speed rail, like the sort seen in China and Europe, entirely new lines would have to be built.

Building that kind of system would be as expensive and lengthy as when the federal government built the highway system. It’s a concept that’s a long way off, if ever.

“Most people are only just starting to think about trains,” Clarke said.

Long road to making it on Amtrak’s map

Knoxville wasn’t the only place left off the map. Kentucky, barring a connection from Louisville to Indianapolis, was left off too, leaving a major gap between the Midwest and Southeast. Getting from Chicago to Atlanta, for instance, means looping through New Orleans.

Magliari said the proposed Amtrak map reflects projects that have long been discussed.

Amtrak discussed the proposed Tennessee routes with state officials early in 2020 and TDOT has discussed the routes since 2000.

The Tennessee House considered legislation to study intercity passenger service to Atlanta but it never reached the governor’s desk. “Unfortunately, like so many things in 2020, it was shunted to the back burner because of the pandemic,” Magliari said.

Serious proposals take a lot of work. Virginia’s proposed service extension to Christenberg is the result of years of planning and organizing.

Residents of Asheville, North Carolina, have advocated off and on to resume passenger service to the city.

“Asheville is on North Carolina’s radar” said Magliari, “But once you get to Asheville you could say, well, what do we do next?”

Could that Asheville service extend through Morristown to Knoxville to Chattanooga?

“Generally speaking routes that have connections on both ends do better than routes that don’t,” Magliari said.

Regional expansion offers a slim hope

Even if high speed rail isn’t possible in the near future, Knoxville could still get basic intercity passenger service if other nearby cities get it.

The Twin Cities of Bristol that span the Tennessee-Virginia border have been pushing since the late ’90s to extend service to their part of the state. Now Bristol is part of Virginia’s state rail plan.

With the recent COVID-19 relief packages and the Biden administration’s willingness to fund infrastructure, people in the area are optimistic about getting the funding needed for necessary track upgrades from Bristol to Roanoke.

Margaret Feierabend, former mayor of Bristol, said that she hopes their efforts will pay off in eight to 10 years. She said that she hoped Tennessee would get on board.

“These lines in Virginia are the lines that Knoxville and Chattanooga would hook onto,” Feierabend said.

History of rail in Knoxville

By the Civil War, passenger rail service connected Knoxville to the other major cities in Tennessee, south to Georgia and as far north as Boston.

Rail helped kick off an explosive growth in population and economic activity in Knoxville. After the war, the rail was the center of Knoxville’s thriving wholesaling business.

The Old City and the Arts District on Gay Street were originally developed as warehouses, shops and salons for the bustling rail.

But passenger rail began to decline after World War II as the interstate highway system was developed and air travel became cheaper.

Knoxville’s last regularly scheduled passenger train pulled out of the Southern Railway Station on Aug 3, 1970.

In the 1970s, President Nixon signed into law the Rail Passenger Service Act, which allowed railroads to cease passenger service, delegating most of it Amtrak.

The Southern Railway company opted out of Amtrak and then canceled service later anyway, leaving Knoxville, and many other cities in the South, without a passenger connection.

In 1979, the Carter administration cut roughly 10,000 miles out of Amtrak’s service area.

The net result of all these cuts are the holes in the service map we see today.

There are only two Amtrak stations in Tennessee, Newbern-Dyersburg and Memphis, both on the City of New Orleans Route that connects Chicago and New Orleans providing infrequent service. Nashville has not had an Amtrak connection since 1979 and Chattanooga, the “Choo Choo City” has not had one since 1970.