Photo by Darin Kamnetz

Ever since the Ichiban Japanese Steak House & Sushi Bar closed in 2016, the building’s iconic, bright blue, pagoda-style roof has served only as a helpful landmark for those lost in the Loring Park neighborhood, just southwest of downtown Minneapolis.

Now, even that roof is gone. By early spring of this year, tarps fluttered between exposed beams where cooks once dazzled over flaming grills. But the easily disoriented, fret not. A new landmark, of equal grandeur, is set to grace the corner of Nicollet Avenue and Grant Street: a massive red stiletto.

The 12-foot, fiberglass heel will stand atop a marquee, marking the arrival of Roxy’s Cabaret. Renovations began after the owners of the nearby Nicollet Diner—a 24-hour neighborhood staple—bought the space in June 2020. Here, a mostly new 14,000-square-foot building will debut bold aesthetics (think: chrome, neon, Airstream-trailer vibes). And on the inside: state-of-the-art drag shows beyond anything yet seen in the Twin Cities—sequined, cinched, and set to lip-sync performances of platinum diva hits.

Jamie Olsen, a drag queen of about 25 years, will serve as the theater’s entertainment impresario. He moved back to the Twin Cities for Roxy’s after having left to run a drag-themed restaurant in St. Louis in 2017. This spring, he walked through the in-progress venue, visualizing his 20-year dream nearly realized. “Stairs will wrap around the elevator and go up all three floors.” He approached a concrete ledge overlooking a space just over 2,000 square feet, to seat 125, and gestured to a 10-by-15-foot, not-yet-existent LED backdrop—“the stage wall will be here.”

Olsen is better known as his drag persona, Nina DiAngelo. With a reputation for sky-high standards, he will oversee the queer artistry, in partnership with the Nicollet Diner’s owners. “We’re going to focus heavily on celebrity impersonation,” he says. Rather than a gay bar, he adds, Roxy’s will function as an “entertainment venue for everyone.” Slated to fill out the cast are local drag star Monica West and BeBe Zahara Benet, winner of the inaugural season of RuPaul’s Drag Race—the reality show that has launched thousands of baby drag performers since it premiered in 2009.

The Nicollet Diner will move in, too, and serve dinner with the shows. (Imagine something along the lines of the Chanhassen Dinner Theatres, Olsen says.) Bars and seating will fill out upper levels, including an enclosed rooftop lounge and a seasonal patio. Expect other entertainment, like comedy and live music—but drag is at the center. The cabaret’s name honors a friend of Olsen’s, local drag legend Roxy Marquis, who died of cancer in 2020.

The goal is for Roxy’s to open ahead of Twin Cities Pride’s 50th anniversary this year (June 25-26). That follows a number of delays, with Olsen in part citing supply-chain issues. Somewhat poetically, the building is about a five-minute walk east of the Loring Park green space, where 50 radicals gathered in 1972 to kick off the city’s first Pride.

Once it opens, the cabaret will apparently make history as the city’s first venue dedicated, from its outset, to drag performance. A 1990s-era remodel of a cramped upstairs stage at the Gay 90’s—the massive, labyrinthine gay bar in downtown Minneapolis—also demonstrated local dedication to drag. But Olsen says that was like “painting a brick” compared with Roxy’s.

Its landmark status offers an opportunity to consider how drag arrived at this point. From vaudeville to downtown’s fabled Gateway District to today’s scene, what has this art form been through, and what has it meant?

Queering the Space

Olsen’s drag style lays a foundation from which to explore the craft’s local history.

Coiffed and padded, Nina DiAngelo has won state and national drag titles, and Olsen formerly served as the Gay 90’s show director. “I never feel more alive than when I’m on stage, being reacted to, whether they’re laughing or crying or wow-ing or ooh-ing or whatever,” he says. “To me, it’s just paying homage to the divas.” Dolly Parton, Barbra Streisand, and Cher are some of his favorites to impersonate.

“Drag,” in this case, does not simply mean “dressing across the gender divide.” History is full of that. Native American civilizations long recognized gender variation, for instance; the term “two-spirit” rose in the 1990s to describe Native identities encapsulating both male and female roles. In another context, “butch” and “femme” lesbian styles in the 1940s pushed gender-nonconforming visibility.

Instead, think of the stage. Around the turn of the 20th century, Minnesota was still a young and fast-growing state. For entertainment, the masses filed into the Pantages, the Orpheum, or the Metropolitan in Minneapolis, or the Grand Opera House in St. Paul. These were middle-class theaters that hosted traveling variety shows—“absolutely the origin of what we now consider to be drag,” says Stewart Van Cleve, author of “Land of 10,000 Loves: A History of Queer Minnesota” and a library director at Minneapolis’ Augsburg University. But this vaudevillian drag “was not at all considered to be a part of what we would now consider an LGBTQ+ sensibility.”

It was more mainstream. Gender impersonators were like warm-up acts, where the appeal lay in illusion and wry sensuality. “As long as you were in that kind of carnivalesque atmosphere of performance, it was OK,” Van Cleve says. “It was approved and generally understood that the performers were considered sex symbols for the opposite sex.” After all, a female impersonator “theoretically embodied what a woman could be.” Local newspapers described certain acts in glowing terms, even as part of a “chaste and elegant” show, in one instance.

But off stage, cross-dressing was illegal. Minneapolis adopted an ordinance against it in 1877, as did St. Paul in 1891. “When you have Norwegian Lutherans, they weren’t going down to Hennepin Avenue to watch the vaudeville shows or the burlesque shows,” Van Cleve notes.

Vaudeville dwindled amid the Depression and the ascendance of TV and radio. Male and female impersonators would split off from bigger vaudeville acts, and their performances would fill more-intimate spaces, where the “fourth wall” threatened to crumble. The risk to mainstream society: fluidity between cross-dressing for entertainment and in real life.

By the ’30s, police were raiding shows. News coverage of drag had soured. Male and female impersonators performed at aging venues while bigger, better theaters rose elsewhere, Van Cleve says. “They’re taking over former theaters, former commercial storefronts that needed that rent money, and we are more willing to entertain a more overtly queer sensibility.”

Some suburbanites from the middle class swung through on “slumming” adventures, to gawk at the supposedly low-brow urban offerings. Whereas the carnivalesque had remained on stage during the vaudeville era, “by the time we get to the Persian Palms, the carnivalesque has come out into the city.”

The Persian Palms, on Washington Avenue in Minneapolis, hosted one of the Twin Cities’ first drag revues. This was the beginning, Van Cleve says, of what would lead to Roxy’s.

A 1949 ad for the Persian Palms in the Minneapolis Star boasts of a New Year’s party full of Hollywood-grade female impersonators, dubbed the “Gay Time Review” [sic]. “If you were a sophisticated urbanite who was in the know, you would have gotten the joke,” Van Cleve says. “Perhaps not everybody did, and that was part of the point.”

The Persian Palms was just one glittering fixture of what was then known as Minneapolis’ Gateway District. Late-1800s ordinances had restricted saloons to this region (among others), where Nicollet, Hennepin, and Washington Avenues converge. First known as “Skid Row,” it was optimistically rebranded as “the Gateway” during early urban renewal. The ordinances meant police could more easily circle the city’s vices. Of course, they also contributed to urban decline, and so these places drew in “undesirables,” such as queer folks. With its aura of disrepute, the Gateway District also provided decent cover for cross-dressing and drag.

In general, Twin Cities’ queer establishments actually appear to have gotten away with relatively few raids. That’s according to an oral history published by the University of Minnesota Press, “Queer Twin Cities.”

Some speculate this was because police raids meant publicity. With a quiet, self-contained queer presence, Minnesota could maintain its moral, exemplary reputation. Another big reason: Bribery was apparently common. Owners could pay to keep the cops out of gay bars.

All the same, a spate of crackdowns swept over drag shows in the late ’40s. In 1949, a popular Miami-based troupe of female impersonators posted up at Curly’s Theater Cafe in Minneapolis—until police requested termination of the contract. Complaints had taken issue not with the Jewel Box Revue itself but rather with the “undesirable people” who hung around. Drag shows were banned from the area for the next five years.

This happened in St. Paul too. Police checked a female-impersonation show at the capital’s Drum nightclub in 1949. Church and civic leaders had reportedly bristled at the “nature of the act.”

Eventually, the Gateway District buckled under its notoriety. City planners had long wanted to redo the Twin Cities’ downtowns, and at last, urban-renewal projects starting in the late 1950s razed much of the region. Many gay, lesbian, and gender-nonconforming people fled southwest into the Loring Park and Uptown areas. Similar St. Paul projects later relocated queer people to Grand Avenue. But drag held on.

Taking the Spotlight

Why do people do drag? And what, exactly, makes it queer? It’s impossible to say definitively. Starting out, it could dissemble same-sex attraction, and it can free gender expression or heighten self-expression. For Julie Dafydd, it was “a means to an end.”

In the ’50s and ’60s, Dafydd had grown up in Soderville, Minn., about 30 minutes north of Minneapolis. “I pretty much knew I was trans all of my life, all through my childhood—although there wasn’t a term, ‘trans,’ at the time,” the 70-year-old says on a Zoom call from her home in Loring Park.

Provided

In her late teens, she found a reference in the local paper to a “transsexual” stripper making a guest appearance at the Gay 90’s. A known spot for drag performances, the steakhouse and strip club was actually “straight” at the time, located inside a large building that had “barely survived” the Gateway District’s decimation, according to Van Cleve. Its name referred to the “happy” 1890s, he notes. Next door, in the same commercial complex, the Happy Hour Bar actually was a known gay bar. If one set of clientele fed the other, Van Cleve isn’t sure which.

Dafydd took a Greyhound bus into Minneapolis. Getting up close to the act, she thought, “‘Yep, it’s me. I get it now.’ Although, I didn’t want to be a stripper,” she says, “but I have been an actress all my life.” School theater had scored her validation amid bullying.

By the early ’70s, Dafydd was attending drag balls at Minneapolis hotels that have since vanished, like the Leamington and the Nicollet. About 100 would enter, she recalls. In her first ball, at age 19, she dressed in matching lingerie with some friends, sang a Herman’s Hermits tune—“There’s a kind of hush all over the world!”—and was named first runner-up. It felt exhilarating. Back then, she says, “the idea was to be as ‘real’ as possible. That was the criteria. Now, drag is a lot more fantasy than it used to be.”

In 1972, a venue for drag shows, called the Club Cabaret, opened on Hennepin Avenue. It was downstairs from the Roaring 20s, a strip club. Both are now a parking lot, but the Club Cabaret was then part of a drag circuit on Hennepin—along with the Club and the Sandbox. For measly pay, performers delivered drag hallmarks: mystique, wit, lip-syncing. Dafydd recalls weeklong rehearsals at the Club Cabaret, going over songs from blockbusters like “Hello, Dolly!” “We had to have some guys in there, too—who else was going to do the lifts?” Meanwhile, she resisted pressure from “the boss” to go upstairs and strip for the other crowd.

By this time, Dafydd says she had been disowned by her family. She instead found community in drag, as many have. But queer spaces have their own issues. “Internal policing” segregated the gay bars by class, race, and gender, as described in the “Queer Twin Cities” oral history. Not many drag performers were people of color in the ’70s, according to Jean-Nickolaus Tretter, who started the University of Minnesota’s storied queer archive. In an interview for “Land of 10,000 Loves,” he says about 10% were people of color.

But Cleo Laine, an African American drag queen, stood apart. She performed at the Sandbox in the ’70s, as well as at the Noble Roman on St. Paul’s Grand Avenue. Taking her name from a jazz singer, Madam Cleo was “the true diva,” says Don Waalen-Radzevicius, who worked for Cleo in the ’80s, when Cleo directed shows and led choreography at the Gay 90’s. “Cleo could morph like there was no tomorrow,” he recalls. “Janet Jackson, Michael Jackson, Dionne Warwick, Tina Turner—[Cleo] was probably one of the first real, real impersonators in the Twin Cities.” (Cleo reportedly died of AIDS complications in 1987.)

The Club Cabaret’s run was short-lived, closing in the ’70s, Dafydd recalls. But a new space for drag was opening at the Gay 90’s, called the Casablanca Show Lounge. Waalen-Radzevicius remembers that upstairs stage: “very small, very dark, very tucked away.” No dressing room, really. Dark enough for “discreet” audience members. Performers sometimes made their grand entrance from a closet.

But through the decades, the Gay 90’s—which went from strip club to disco in 1976—would rebuild itself into a premier drag space. Waalen-Radzevicius was show director in the 1990s and worked with the owner to knock down walls, expand, and change the name to the “semi-exotic” La Femme.

“And the drag show wasn’t this little, tiny-kept secret anymore—it was like, boom,” Olsen, who started working there in the late ’90s, recalls. “That rubbed some people the wrong way. They wanted to have the best-kept secret, or whatever, kind of along the same lines of the thinking of the gay bar in general—the people that still want that old gay bar, [with] the dark corners. I just don’t think that exists anymore.”

Provided

In the ’90s, drag appeared to be fed up with “dark corners” and was sashaying more broadly into movies and media (“The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert;” “To Wong Foo, Thanks for Everything! Julie Newmar”), causing some to lament the queer art’s “mainstream” emergence. Mario Maldonado moved to the Twin Cities in ’94, as drag celebrity RuPaul’s hit song “Supermodel” made waves. Originally from El Salvador, Maldonado first did drag in ’98 for a Gay 90’s contest (dressed as Cyndi Lauper for Halloween), and he would come into his own as La Coco Villeda. He would perform at “every single Latino bar” for pay that he says failed to match the business he drew in (maybe $75, $100 a night).

But then there was Margarita Bella. Opening in ’98 in northeast Minneapolis, the now-closed Latin bar expanded its “gay nights” when it came under gay ownership in 2001. “It was a gay community, and there was a mix from everywhere—South America, Central America, Mexico, and from here, too,” Maldonado recalls. If gay Latinos didn’t always feel welcome in white queer spaces, he says, Margarita Bella was home, and the tipping was good. “Now you can make, like, a couple hundred bucks in one or three numbers, because why? Because there’s a lot of gay people there. And the gay people—we know we have to tip the drag queen.”

In the early 2000s, Maldonado also started doing drag during the Latin nights at the Saloon, the gay bar in downtown Minneapolis that opened in 1977. As La Coco, he began handing out condoms and offered HIV testing there, as well as at Margarita Bella and other gay hangouts, originally in response to the high rates of infection in Latin communities. “Every single night” at Margarita Bella, he says, “I would say, ‘There is a table—take whatever you need. Share with people. Bring to your family.’”

Today, that tradition of mutual support remains a part of drag. And Dafydd plays a leading role in one of its local outlets.

Trans and cisgender women do drag, but the gay community had made it feel “verboten” to Dafydd after she underwent gender-affirmation surgery in 1976. These days, she acts in plays across the country—and occasionally dips back into drag in her role as “Queen Mother for Life” of the Imperial Court of Minnesota.

This grassroots group crowns drag royalty, raises funds for LGBTQ+ causes, and has chapters continent-wide as one of the world’s oldest LGBTQ+ organizations, founded in 1965. “It takes a certain amount of bravery, it takes courage to be a drag queen,” Dafydd says. “There’s people that will always have judgment about it, even in the gay community. But the drag community is always the first to give back, to contribute. It’s a great way to get an audience to give their money. ‘Give me your dollar; it’s going to charity,’ you know? And that’s what we do.”

She continues, “True altruism, you know—there’s got to be getting something back. It has to be worthwhile to you, it has to be fun, and it has to be with people who are going to be understanding and supportive of who you are. Family!”

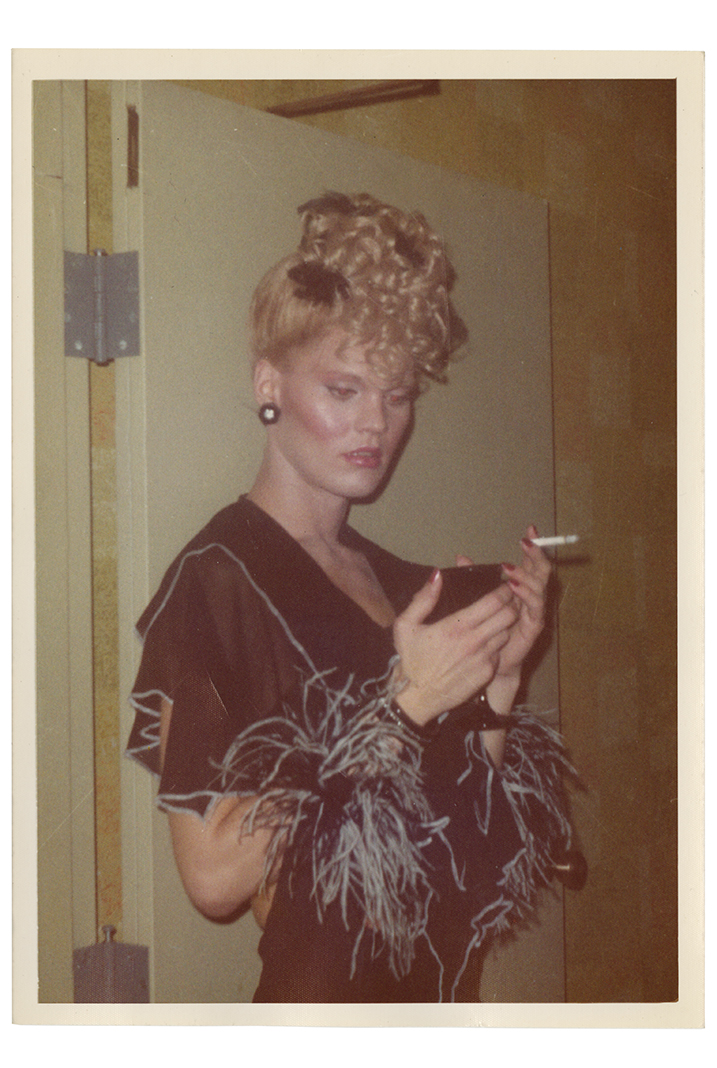

Photo by Barb McLean

Building New Landmarks

Across the river from Minneapolis, a queer legacy lives on in the Hamline-Midway neighborhood of St. Paul, in an unassuming spot along University Avenue.

Here, on a recent Friday night at the divey Black Hart of Saint Paul, Zsuzsi Borzalski performed as the spiky-haired protagonist of Disney’s “Wreck-It Ralph”—hands stuffed inside big foamy fists, feet hopping to Kenny Loggins’ “Footloose.” This was the same stage and dance floor that once defined the Town House, St. Paul’s oldest gay bar before it got a name change in 2018.

“Dragged Out” is the bar’s monthly drag-king show, organized by Borzalski, who identifies as agender and goes by Xavier in drag. It’s worth noting here that drag kings have received less attention than drag queens for decades. Possibly seen as threats to masculinity, “male impersonators” even disappeared from local newspapers after 1921, according to a former archival digitization technician at the Minnesota Historical Society. Borzalski says a queen once told them, “Drag queens dress up; drag kings dress down.” But the kings performing elaborate numbers on Friday night did not lack ferocity, with pistols whipped, a guitar shredded, and a flower beheaded. Borzalski suggests cis male privilege—in income, for instance—may have historically offered certain drag queens a leg up.

Borzalski got started in drag 20 years ago. At that point, St. Paul’s Club Metro had just closed. “How the Gay 90’s is so big and has so many spaces—Club Metro was basically like that … but even better,” Borzalski recalls. The venue’s drag stars moved on, and Borzalski and a group of beginners decided to start their own show. They churned through a number of establishments. First, they performed at Over the Rainbow Jr., then at Lucy’s, and then at the Town House, as one queer St. Paul spot closed after the other.

Eventually, the Town House’s owner wanted to sell. It would go to a straight cis man who had a soccer bar in mind. “Sports fans and queer bars is probably not going to mix,” Borzalski recalls thinking. But in a twist that should blueprint a movie, owner Wes Burdine took the queer history to heart. “We have staff who have been there for 18 years,” reflects Burdine, who says he has connected with trans and lesbian regulars. “We didn’t change any of the shows when we came in”—and he says he has since witnessed camaraderie among the worlds-apart patrons.

Photo by Dain Rodriguez

Kevin Billups, who does drag as Lala Luzious, recently launched the drag revue “Power,” after moving to the Twin Cities from Indiana four years ago. Coming from a place without any gay bars, Billups found the Twin Cities rich with opportunity. Among the drag scenes Billups has experienced, including in New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles, “Minneapolis has the best variety that also matches quality,” he says.

Chad Kampe, owner of the Flip Phone event company known for hosting drag-brunch blowouts, offers an explanation: The cost of living is less than in bigger cities, and winter “forces people to be inside and be creative.”

Andrew Rausch performs as Crystal Belle and co-owns the reopened, remodeled Lush in northeast Minneapolis, a high-production yet practically intimate drag venue. Rausch helps break down the local scene: The Gay 90’s is classic drag, “the bachelorette-party capital of the world,” and “like the Spice Girls—you get a little bit of everything;” downtown Minneapolis’ Saloon “has a little more punk-rock alt drag in it;” Lush is a “potpourri,” with a cast of pageant queens, a drag king, and some spunky beginners; the Black Hart of Saint Paul similarly incubates “bud-of-a-tree” drag; and the events by Flip Phone are “turn-and-burn, cut-and-dry” moneymakers.

Independent shows, such as “Queerdo” at Minneapolis’ Meteor cocktail bar, display drag’s rainbow of influences. After all, for every bejeweled goddess, a mustachioed queen in a cow costume is singing a version of “Someone Like You” that swaps Adele’s heartfelt “you” for a bovine warble.

There’s a local tradition of camp here: Minnesota’s original drag celebrity is Miss Richfield 1981, the bouffant-headed, bespectacled, always-beaming Midwest caricature who has honed ditzy cabaret flair since she started in the ’90s. Since then, Miss Richfield has starred in Orbitz commercials and has long performed at Minneapolis’ Bryant-Lake Bowl—which is also where the punk-cabaret group Dykes Do Drag have left a colorful, queer skidmark trailing back to 1999.

Updating Tradition

At Roxy’s, the Twin Cities’ next big deal in queer performance, Olsen wants to continue a stylistic tradition of drag—of polished impersonation and exacting attention to detail—while upholding the drag mantle of charity carried forth by people like Dafydd.

“I would love to have a workshop where women of color can come in and have the queens show them how to do their makeup for a job interview, or make sure they have great clothes to go to an interview, or team up with somebody like Turn Style [Consignment],” he says.

Olsen’s desire for Roxy’s to be open to everybody—with the venue expressly not a gay bar—also plays into an ongoing discourse about how people, especially straight ones, should occupy queer space.

There’s some local history here: “For a long time, there have been instances where queer folks police queer space and ensure that only queer folks are using that space,” Van Cleve says. That goes for the Gateway District, where patrons of gay bars traded in codes, through clothes, mannerisms, or words. At one gay bar, called the Onyx, people wore green, for example.

In the ’70s, too, the second floor of the Orpheum was “for drag queens and their boyfriends,” Van Cleve says, quoting one of his sources. “There was a bouncer at the top of the stairs who decided if you were queer enough to come in.”

That sense of exclusivity has involved safety, comfort, and relief for queer people. These days, for Billups, respect is paramount for anyone who wants to attend a drag show. That means, for example, not giving queens unsolicited makeup tips, not getting too drunk and rowdy, not commandeering the space as part of a bachelorette party. “When I started [in 2006 or 2007], drag queens, or any type of fringe performer, was the butt of the joke,” Billups recalls. “Today, I walk into the room and I actually feel like a queen. I feel like royalty. I feel respected for what I do. I feel that people are engaged in a way that’s not humorous—what they do is actually art.”

Looking out into the audience, “I want everyone to have a good time,” he says. “It’s not really my business who they’re sleeping with, or what their orientation is, or even what other problems they have in their life. It’s my responsibility to make them forget about it.”

For Roxy’s, inclusivity is a matter of following through on the LGBTQ+ community’s welcoming ethos, Olsen says. “We can’t talk acceptance and inclusion out the one side of our mouth and then be exclusive and excluding on the other side.”

And, in business terms, it’s about staying viable. When Olsen ran the drag restaurant in St. Louis, he says some 80% of money came from straight people. “[Roxy’s is] not going to be labeled a gay bar, but there’s going to be a lot of gay stuff happening,” he says. “If you want to support your community and be present in a space, then do it.”

Taking a step back, this appears to be how drag updates itself: in ways that both honor history and claim more and more for itself.

Nationally known male and female impersonators once lit up cities on the vaudeville circuit. Now, Flip Phone helps local queens light up people’s phones, with a popular presence on the TikTok video-sharing app. The company has been scaling up. Last year, Flip Phone expanded to New York City and Chicago, and Out magazine even named Flip Phone show director Harry Mason, who does drag as Sasha Cassadine, one of 2021’s “Top 30 Names in Queer Nightlife.”

Other legacies, meanwhile, feel more like works in progress. An almost 17-year veteran of Twin Cities drag, Mason has decried pay inequities between performers of color and their white counterparts. “A lot of people are starting to realize—don’t pay for the skin, pay for the work,” Mason says, adding that he has seen improvements in the Twin Cities scene.

Roxy’s represents another kind of progress. Far from “warm-up” acts, drag queens here will hold the spotlight, inheriting a legacy that now seems fully resistant to bulldozers, with the fresh lives of Lush and the Black Hart suggesting as much, too.

The remodeled show lounge at Lush, in fact, contains another, separate tribute to Roxy Marquis. A portrait of her towers near the stage, beside a poem she wrote after her cancer diagnosis. “I will follow the Queen into our next battle,” the plaque reads. “And I will drink as much joy as I can along the way.”