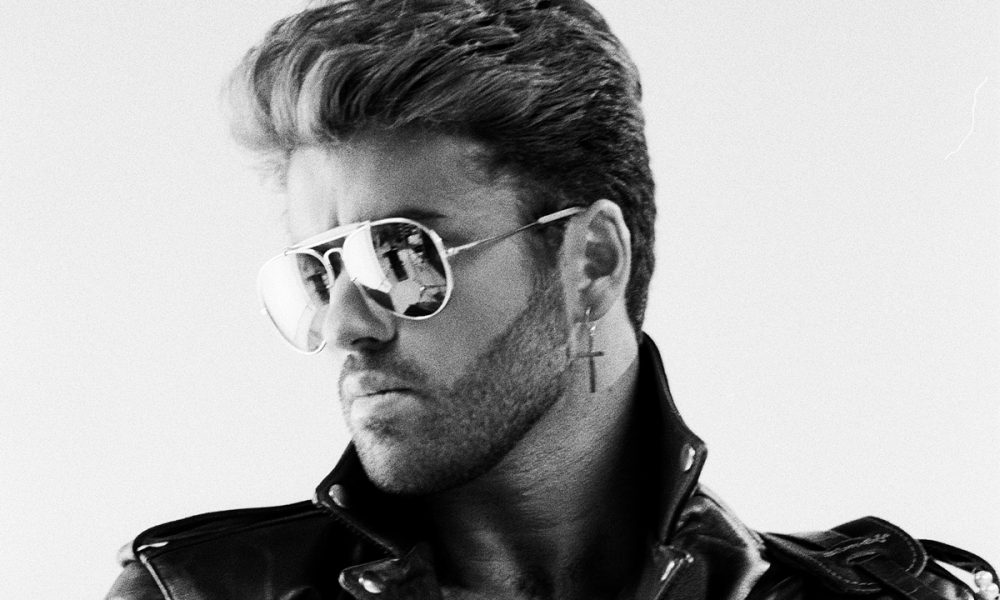

Of all the great songs the late George Michael left as a legacy, “Careless Whisper” is certainly among the greatest – and yet, ironically, he never really liked it.

“He said he was ashamed of it,” says Simon Napier-Bell, who was Michael’s manager during the WHAM! years. “It had come to him in a moment, and he liked to sit and think about everything he wrote, what he wanted to say. This one just popped out, and it was like, ‘Fuck me, I’ve given away my inner self and I didn’t even know I was doing it.’”

Napier-Bell, now 80, is a music industry veteran with a long roster of legendary clients. In recent years, he’s turned to making documentaries – and his latest effort, “George Michael: Portrait of An Artist,” provides a comprehensive look at the life of his now-iconic former client. And yes, it deals with the proverbial elephant in the room – Michael’s 1998 “lewd conduct” entrapment arrest for cruising in a Beverly Hills men’s room.

In the film, which documents the musician’s public and private lives side-by-side and sheds insight on the difficult balancing act he tried to maintain between his star image and his authentic self, the incident is just part of Michael’s larger story. It’s a key moment, however. For a younger generation, Michael’s “notorious” bathroom incident often overshadows his musical legacy, and some judge him harshly for remaining closeted through so much of his career. As Napier-Bell – an out and proud gay man himself – told the Blade, they couldn’t view him any more harshly for it than he did himself – but in the 1980s, if he wanted the level of stardom he was capable of achieving, he had no choice but to keep his sexuality hidden.

“Every artist has the problem of balancing their desire for artistic perfection with the needs of the industry and the struggle with their own demons,” says the director. “People say stars are uncompromising, but it’s the very opposite – the music industry DEMANDS compromise. George had a dislike of having to compromise, and a lot of guilt for not coming out, which he knew he ought to do.”

Though his documentary doesn’t get granular about the timeline of Michael’s coming out process, the filmmaker claims the singer toyed with the idea in his earliest days of success yet held back when it became clear his record label would not allow it. Instead, says Napier-Bell, he planned to build his career and then come out when he was already a star. But then, as the director remembers, AIDS happened.

“Young people today really don’t understand,” he says. “I recall standing in the balcony of Heaven, THE huge gay club in London at the time, with Paul Gambaccini [a UK broadcast celebrity and author who appears in the film], and he pointed down at the enormous crowd of dancing people pressed together and said to me, ‘Do you realize that nearly half of these guys are going to be dead in five years?’ It was such an outrageous thing to say, you wanted to think maybe four or five of them might get it – but he was absolutely right.”

With fear of the disease setting back gay acceptance on both sides of the Atlantic – “If you knew someone was gay in the 1990s you stayed away from them,” he recalls, “not just straight people but other gays as well” – Michael remained in the closet.

Still, for many in the public, his sexuality was no secret. Despite the heteronormative image he continued to project, millions of queer fans recognized his truth and related to him for it, and many of his straight female followers sensed it, too. Napier-Bell recalls talking to girls at George’s gigs and asking if they fancied him. “They would say ‘Oh, he’s fabulous! But that’s not really possible, is it?’”

It was not until 15 years later that Michael’s closet door was finally flung open by that Beverly Hills arrest. With his secret exposed, there was no reason to hide anymore. He tried to turn the moment to his favor, seizing the opportunity to come out proudly and advocate against homophobic law enforcement policies that targeted gay men for having consensual sex; the world, however, was not quite ready then to embrace his attempt at a sex-positive stance, and both his image and career sustained lingering damage.

Though he can’t know for sure and has no information to confirm his suspicion, Napier-Bell believes Michael intended – “at a highly conscious subconscious level, just near the top of the subconscious, I should think” – to get caught.

“When I was managing him with WHAM!, he was going to gay clubs – and it wasn’t because he wanted sex, because he was getting that anyway. He was doing it because he really wanted to be outed – you could see it – but didn’t know how to come out.”

Later, Michael would often flaunt his queerness in public. “He would be giving an interview, and Kenny [Goss, his longtime partner] would be off camera and say to him, ‘I’m going now, darling’ and he would say, ‘Oh, see you at home, put the kettle on,’ and blow him a kiss.’ He wanted to show that it was just like being straight, just like being married.”

The arrest, intentional or not, may have liberated him from the closet once and for all, but it also tarnished him in the eyes of many of his LGBTQ fans. “He did a huge amount of good by projecting a positive image,” says Napier-Bell, “but then he complicated it with defending cruising and not being monogamous. He never got to a simple position on all that, did he?”

Michael would continue to be in the public eye, but his star faded steadily – partly, Napier-Bell believes, because he encouraged it to do so – and he struggled with substance abuse. He died at 53 in 2016, officially of heart disease.

Reflecting now, Napier-Bell believes that Michael’s star has “gotten bigger” since his death, something he says is “rare for any musical artist,” in large part because of the inner conflicts that haunted his life and found expression in his songs.

“All his struggles – being trapped in the closet, his boyfriend dying of AIDS, his disastrous ending – give us something we can identify with. We project our happy lives when we leave the building, when we’re social. He didn’t just come out about sex, he came out about being fucked up, about his life being difficult. We need people to talk about these things, and to have all that angst projected through his life and his songs is very comforting, for everybody.

“People say it was sad, but life doesn’t have a happy end,” Napier-Bell says. “If you’ve written one of the three biggest Christmas songs in history, it’s not a bad day to die. And his overall canon is pretty dang good. I think he would have been happy with that outcome.“

“George Michael: Portrait of an Artist” is available on demand from Amazon Prime Video, Apple iTunes, and Google Play.