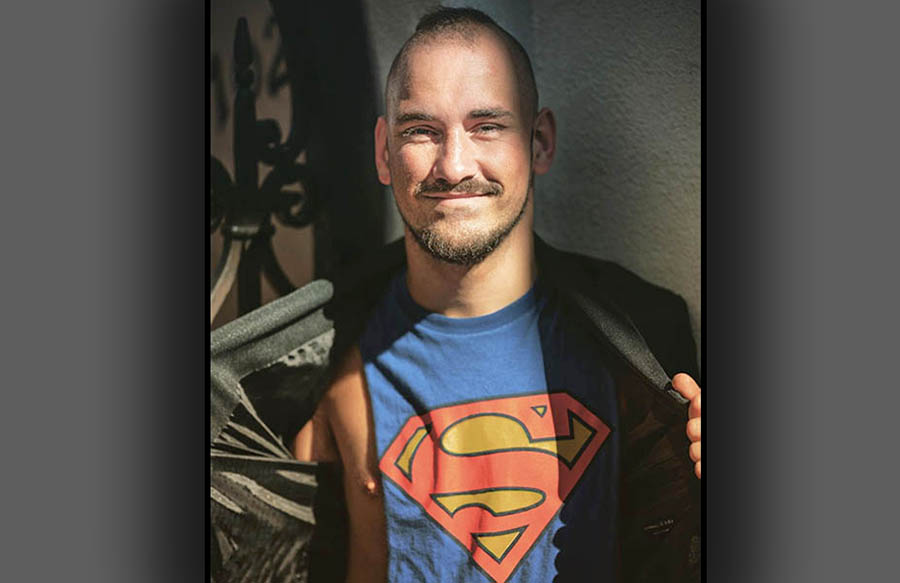

For Aleks Hatzigeorgiou, a first-year international business major, Boston’s accepting environment was a dramatic change from his hometown of Augusta, Georgia.

There is a small LGBTQ+ community in Augusta, Hatzigergiou said. Pride flags are only displayed on stickers in the windows of a few downtown businesses. Growing up in the more suburban area of the city, Hatzigeorgiou said he rarely saw anything related to LGBTQ+ acceptance and pride.

“Boston is a lot different,” Hatzigeorgiou said. “It’s a really diverse community of not only gay people, but lots of other people. Everyone is more accepting in many ways, especially sexuality.”

Hatzigeorgiou’s story is not unique — many LGBTQ+ people, including gay men, flock from all across the nation and the globe to come to Boston, often to seek higher education and a more accepting environment. According to a May 2018 study conducted by Boston Indicators and The Fenway Institute, nearly 16% of adults in Massachusetts aged 18-24 identified as lesbian, gay, bisexual or another LGBTQ+ identity.

In Suffolk County, 8.1% of adults, defined as 18 or older, identified as LGBTQ+. This is just behind Hampshire County’s 9.0%, making Suffolk County second in the state in LGBTQ+ population density. The study states that “Massachusetts is also home to some of the most cutting edge and innovative pro-LGBT social services, community resources and public policies.”

Hatzigeorgiou said he thinks the accepting attitudes of many in Boston have allowed him to be more open about his sexuality since arriving in the city, even allowing him to feel comfortable enough to rush and pledge a fraternity this fall.

“I didn’t go into Northeastern thinking I wanted to rush, just because of my experience with fraternities down south,” Hatzigeorgiou said. “But fraternities here are all of the pros of a frat and none of the negatives, at least with Beta [Theta Pi]. It’s a really positive, uplifting community, and there’s a lot of diversity in the frat.”

James Tully, a first-year bioengineering major, echoed a similar sentiment on coming to Boston from his small hometown of Camillus, New York, just outside of Syracuse. Before he came to Boston, Tully was only out to his immediate family and a few close friends.

“Boston is definitely a lot more liberal and open; I’m not afraid to talk to people about [my sexuality] here,” Tully said. “It’s not really different than what I knew at home because I wasn’t really out, so this is my first experience, but it’s been a good one, I’d say.”

However, there have been some instances throughout his time at Northeastern where Tully has been made uncomfortable by the comments of his peers.

“Boston-wise, there’s been people here that I tend to notice being a little passive-aggressive towards me,” Tully said. “What they think is a joke is not really funny and is quite offensive. But I tend to stay away from those people.”

Tully said that while he would rather avoid the people that make inappropriate jokes or comments, Northeastern’s policies on harassment based on sexual orientation offer him sufficient protection and support if the harassment were ever to evolve to an unmanageable level.

Alex Cordova, a fourth-year behavior neuroscience major, said his time in Boston has also allowed his sexuality to flourish after moving here from Seattle.

“I’ve definitely become a lot more comfortable with [my sexuality], and I think that’s from finding people that I’ve been comfortable with and being able to engage with more queer people my own age,” Cordova said. “Now, I live in a bubble, essentially. Nearly all of my friends [in Boston] are queer, and it’s affirming.”

However, when Cordova goes back into straight-dominated spaces, he said he often reverts to staying alert.

“Being thrown back into those non-queer majority environments, I might feel my guard go back up again … I mean, no one has gone out of their way here to make me feel uncomfortable,” Cordova said. “I think that might have to do with my existence as a queer person, to an extent. I’m always aware of my environment.”

Even though Cordova’s experiences in Boston have been overwhelmingly positive, he said Boston is lacking in one key area in comparison to many other cities of its size: a centralized LGBTQ+ neighborhood.

“Seattle, for example, has Capitol Hill, which is historically, socially and politically very queer … and almost all of the businesses are queer-owned,” Cordova said. “Here, I’ve found it a bit more difficult to find queer spaces outside of bars and clubs, specifically Club Café. A lot of the queer-centered spaces are just limited to nightlife.”

Club Café, a gay nightclub on Columbus Avenue, is one of Boston’s few LGBTQ+ gathering spaces, specifically marketed towards gay and bisexual men. The number of gay bars and nightclubs in Boston has decreased, with institutions such as The Eagle, Machine Nightclub and Ramrod all closing their doors permanently within the last few years. Boston is following the national trend of shrinking options for gay nightlife, which is a problem that has been exacerbated by COVID-19 restrictions. And, for Hatzigeorgiou and Tully, who are not yet 21, these dwindling spaces are inaccessible.

Despite all of this, Cordova, Hatzigeorgiou and Tully all acknowledge that cisgender gay and bisexual men are in a place of privilege within the LGBTQ+ community.

“I definitely think that gay men have privilege over a slew of other people in the LGBTQ+ community, especially white gay men,” Tully said.

Cordova agreed, stating that toxic masculinity plays a role in white gay men’s privilege.

“I’m half Asian, and I want to say that there’s a very strong white gay majority, and that’s where I’ve seen [toxic masculinity] pervade the most,” Cordova said. “A lot of [white gay men] are still clinging on to that masculinity — that idea of ‘I’m not like other gays,’ and I’ve seen that energy directed to queer people of color.”

Even though the LGBTQ+ community still faces challenges, Cordova, Hatzigeorgiou and Tully all retain hope for their futures in Boston, as well as the LGBTQ+ community in the city.

“People [in Boston] are a lot more vocal, expressive and passionate, which I see in both queer and straight communities,” Cordova said. “Being a student in a city of students does give me hope, at least to an extent, and the acceptance that I’ve had the privilege of meeting in my experience here gives me hope for future queer students.”