My family raised me largely on misinformation about HIV and AIDS. It was, they said, a disease that gay men got from having anal sex. When diagnosed, the disease was swift—very Philadelphia in context. Perhaps that comes from being born in the midst of the AIDS crisis. Perhaps it comes from having a family that was overwhelmingly prejudiced against the LGBTQ+ community. I can’t be sure. But as I came out and educated myself, I realized that most of that misinformation is learned, fertilized by hate, and rooted in homophobia.

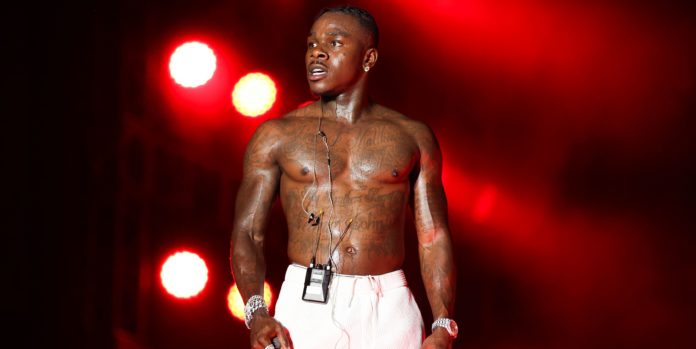

This past weekend at Rolling Loud festival in Miami, rapper DaBaby spent a portion of his set making deeply homophobic comments from the stage. That’s not up for debate. He first disparaged people diagnosed with HIV or AIDS, then gay men. There didn’t seem to be a specific catalyst that prompted his remarks, but then again, even if there were, it doesn’t warrant explanation, nor could it serve sufficiently as an excuse.

On Monday, the 29-year-old, Grammy-nominated artist defended his quotes. Not 48 hours later, however, as he started losing sponsorship deals, he tried to walk those statements back. He tweeted, “Anybody who done ever been effected [sic] by AIDS/HIV y’all got the right to be upset, what I said was insensitive even though I have no intentions on offending anybody. So my apologies. But the LGBTQ+ community… I ain’t trippin on y’all, do you. Y’all business is y’all business.”

The thing is, he made it his business when he decided to chime in despite no one hitting his buzzer. On Wednesday, Elton John caught wind of the situation and waded into the conversation. (Usually, when you’ve tapped Elton into the conversation, it spells trouble ahead.) The singer decided to use his platform to spread correct information about HIV and AIDS via a Twitter thread.

This content is imported from Twitter. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

We’re going to do the same.

An Early History of AIDS

In 1980, the first American case of AIDS was reported, though, because so little was known about the disease, an official, named-diagnosis wasn’t made until 1981. At that point, AIDS was widely known as GRID, or gay-related immunodeficiency. The New York Times first reported on it in July of 1981, using the headline “Rare Cancer Seen in 41 Homosexuals.” In 1982, the publication addressed the disease as A.I.D., or autoimmune deficiency. The illness continued to be known as a “gay disease,” despite cases being reported in both gay and straight individuals. And it’s that misconception that has fueled the homophobic sentiment that connects queerness with an HIV positive status. To make matters worse, because the LGBTQ+ community has a history of being ostracized and vilified by the U.S. government, as well as society at large, the belief that it was solely a “gay disease” made medical progress on AIDS and HIV difficult. The government power at the time often labeled it “the gay plague,” and treated it as a moral and religious issue, not a medical one. It limited money allotted to research, controlled the public narrative, and largely, ignored the people that were dying. LGBTQ+ people and straight people paid the price of an apathetic government.

Throughout the ’80s, cases of AIDS grew at an exorbitant rate. By the time Reagan took the presidency in 1984, the numbers were staggering. The AIDS crisis had become an international issue. Reagan’s administration was criticized for doing next to nothing to stop the spread of the disease, and the stories that have bubbled up since his terms in office are bleak.

Accounts of the press pool at the time include regular laughter when the disease was brought up while Reagan’s press secretary, Lester Speakes, routinely made jokes about the disease as deaths rose into the tens of thousands. Another account alleges that a Reagan official once joked that they should give a Libyan leader AIDS. And First Lady Nancy Reagan was rumored to have only first taken the disease more seriously once she learned her friend, Rock Hudson, was dying from it.

In 1986, HIV is suggested to be the retrovirus that causes AIDS. And in 1987, the drug AZT (zidovudine) is introduced to the market; because of limited medical access to Black and queer people, who were disproportionately affected by the disease, the ability to get treatment was difficult. Even as the disease began to be treated more seriously in the early ’90s, AIDS and HIV continued to be a punchline and an assumed “death sentence” for those who were living with the disease. At the same time, public figures like Magic Johnson (who manages his diagnosis to this day) shed light on the disease. And medical trials at the time prove that treatment can not only help those affected by HIV and AIDS, but also the offspring of those who become pregnant after diagnosis.

A Vocabulary Lesson

People do not get AIDS. They get HIV, which then turns into AIDS. As described by the CDC, “HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) is a virus that attacks the body’s immune system.” It is hypothesized that HIV can be traced back to a chimpanzee in Africa, and was likely acquired through the hunting of meat and contact with infected blood. Researchers suggest that it likely dates back to the 1800s.

AIDS is the advanced stage of HIV, which is scientifically classified as “a diagnosis when [a patient’s] CD4 cell count drops below 200 cells/mm, or if they develop certain opportunistic infections.” CD4 cells are also known as T-cells. Those cells help fight infection in your body and are integral to your immune system. Keep that “T-cell” vocabulary in your back pocket. It’s coming back later.

People who have progressed into full-blown AIDS and remain untreated typically have a lifespan of about three years, according to the CDC.

Breakthroughs You Need to Know About

AZT was approved by the FDA in 1987. The way it works is that, in combination with other antiviral drugs, it attacks “an enzyme called reverse transcriptase, which is used by retroviruses such as HIV to replicate viral single-stranded RNA (ribonucleic acid) into proviral double-stranded DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid),” according to Brittanica. In laymen’s terms: It slows the progress of the disease so that it doesn’t reach extreme levels that lead into AIDS. And since we’re talking about extreme levels, it’s important to note that AIDS weakens the immune system so that diseases can more easily replicate and attack the body, which is why it’s more common to hear of “dying from AIDS-related illnesses” not “dying from AIDS.”

Today, living with HIV is entirely sustainable for those who are infected. And since AZT’s introduction, there have been other treatments—often referred to as antiretroviral therapy, or ART—that are effective in controlling the disease. Typically, if HIV patients begin addressing the disease soon after being diagnosed, it can be at a controllable level within six months, according to the CDC. And those first few months are important—early HIV symptoms can seem like a bad flu or a cold. That’s when the virus is at its most contagious. Because it presents as something so mild, that makes regular testing for those at risk all the more important. But contracting the disease isn’t some kind of scarlet letter. People can lead “normal” (subjective, we know), healthy lives with an HIV diagnosis without having to worry about passing the disease onto a partner.

Let’s go back to that T-cell count we were talking about. As long as a person’s T-cell count remains high and the viral load remains low, which can typically be easily managed with ART, a person with HIV has an increasingly low chance of spreading the disease to a partner. At a point, the viral load becomes what is known as “undetectable.” That means it exists in the body, but is so scarce that there is “effectively no risk” to spread it to partners through sex. The rate of transmission through drug use is also lowered.

In recent years, other drugs including Truvada (or PrEP), have revolutionized the fight against HIV and AIDS. PrEP, or pre-exposure prophylaxis, is a once daily medicine that those who do not have the disease but are considered “high risk” can take to help greatly lower the risk of getting the disease, if they come in contact with it.

In conclusion, the first step against ignorance is education. Exposure to people unlike yourself also helps. And listen, I can’t get in DaBaby’s head and make sense of his own biases or the place where he crafted those comments. But I do know that they’re tired. It’s a stereotype that has ventured from the point of being offensive and shocking to being offensive and boring. And the history of homophobia in rap music, which has in recent years appeared to be improving, is long and well-documented.

But to write all this up means that you have to believe in the power that people have to change. When my family—the ones who sold AIDS to me as a gay disease that kills quickly—found out that a straight relative of ours had a positive HIV status, it changed the way they saw the world. She lives every day of her life fully, thanks to a bit of medication and lot of knowledge. Fortunately, the key to not talking out of your ass isn’t dependent on knowing a person with HIV or AIDS. Or even knowing a gay person. It really starts with your desire to do better.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io