|

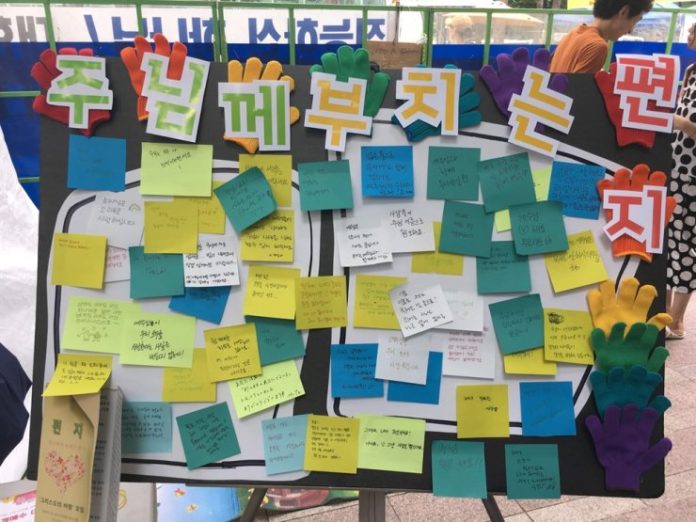

| Post-it notes at 2018 Seoul Queer Culture Festival / Courtesy of Joseph Yi |

By Joseph Yi

|

| Joseph Yi, associate professor of political science at Hanyang University |

The long-simmering “culture war” between Christians and the LGBTQ community seemingly escalated in the first half of 2021. Theologically conservative evangelical Christians forcefully blocked an anti-discrimination bill sponsored by the left-leaning Justice Party in the National Assembly, and LGBTQ activists rallied around Methodist pastor Lee Dong-hwan, who appealed his two-year suspension from the Korean Methodist Church (KMC) for holding a blessing prayer at the 2019 Incheon Queer Culture Festival. Lee’s case, in particular, received international publicity, as he received an International Amnesty Media Award in March and a personal, supportive meeting with Canadian Ambassador Michael Danagher on May 17.

As academic researchers on Christian-LGBT relations, we find that culture war narratives are shaped primarily by a small number of activists, whose voices are amplified by the mainstream media. These narratives ignore the vast numbers, perhaps a majority, of both LGBTQ persons and Christians that do not view the other as implacable enemies and are open to communication and compromise.

Through our fieldwork, we talked with many activists from both communities, who said that ―although organizationally they feel pressured to treat the other side as a threat ― individually, they did not harbor such intense sentiments. The capacity to view the other as complex human beings is more salient among persons who experienced sustained, interpersonal contact with members of the opposite group.

Our longitudinal analysis of Christian media (1998-2019) finds more nuanced, sympathetic discourse towards LGBT persons in the past decade. Most Christian media articles discussed the “culture war” between conservative Christians and the LGBTQ community, but a growing number sympathized with the struggles of LGBTQ persons, especially that of “gay” Christians who struggled to reconcile their sexual and religious identities and who were abandoned (or were afraid to be abandoned) by their churches.

The shifts in Christian discourse towards the LGBT outgroup in the 2010s parallel that towards another historic outgroup, North Koreans in the 1990s. Christian media actively reported on the dire conditions of North Koreans during and after the “Arduous March” famine in the mid-1990s. Many South Korean Christians reached out to North Korean people offering humanitarian assistance, without endorsing the North Korean regime or its communist ideology. Before recent sanctions and pandemic-related border closures, Christians had developed robust, person-to-person engagement with North Koreans, including a Christian-operated Pyongyang University of Science and Technology, medical center for disabled persons Pyongyang Spine Rehabilitation Center, and surfing camp.

The post-1990 engagement with North Koreans, despite political-ideological differences, offers a template for Christians to humanely dialogue and interact with LGBTQ persons. A small, growing number of Christian organizations seek dialogue and mutual understanding between the two communities. They include small, progressive-leaning, Christian organizations (that bless same-sex marriage), such as Sumdol Hyanglin Church, Pilgrimage Church, Rodem Church, Queer Faith Korea and Open Doors MCC. More conservative-leaning organizations include Seoul Calvary Chapel, Bundang Woori Church and some others that work anonymously with LGBTQ persons.

At the past five Seoul Queer Culture Festivals, a conservative, evangelical group freely offered cold bottles of water at the event which was held on a hot summer day. The water symbolized the Fountain of Life (“Living Water”) found in Jesus. Many festival participants appreciated the bottled water, and a few attended the group’s church service the following Sunday. The evangelical group and its pastor focused on interpersonal relations, not politics, at the Queer Festival.

We do not downplay serious disagreements between LGBTQ persons and Christians. Still, we highlight ― and encourage ― those many individuals, in both communities, that wish to talk and find common ground. Kind, civil gestures, big and small ― starting with sharing cold water on a hot day ― nurture an atmosphere conducive to communication and compromise, such as on legislation that protects the vital rights of both communities. We can learn from examples in other countries, for instance, in the U.S. state of Utah, Mormon Church leaders and LGBT rights advocates compromised on state legislation to protect both LGBTQ persons and marriage traditionalists from employment discrimination.

In today’s polarized world, we have turned away from complex realities outside our narrow social circles. Behind political-ideological differences lies a person with a unique story, some of them serving actively in churches, with personal dreams and aspirations. We have witnessed their internal struggles adjusting to their faith communities and looking for a safe space to fulfill their spiritual needs. The state cannot enforce the Christian principle of loving one’s neighbor. It is up to individuals to listen to, and interact with, each other for a healthy coexistence.

Whatever our disagreements, we can agree that every life is precious and deserves to be loved. Our democracy promotes liberty and flourishing for all.

Joseph Yi (joyichicago@yahoo.com) is an associate professor of Political Science at Hanyang University. Wondong Lee, a Ph.D. student in Political Science at the University of California, Irvine, and Saul Serna, an assistant professor of Social Sciences at Woosong University, contributed to this article.