Elsewhere, he tells a secondhand version of Fauci’s account of the creation of the Vaccine Research Center (part of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, which Fauci has directed since 1984). “Around the midpoint of his presidency,” Quammen writes, Bill Clinton “got very interested in the imperative of conquering AIDS.” He asked Fauci what he needed “to really solve this problem once and for all.” When Fauci answered that he wanted to create a center focused on developing an AIDS vaccine, Clinton looked to his chief of staff and said imperiously, “Leon, just get this done.” It’s a cute little story if you find power enchanting—and unless you remember that, by that time, the AIDS pandemic had been devastating gay communities for a decade and a half. For more than half of that period, AIDS activists had been so enraged by Fauci’s inaction that they routinely called him a murderer.

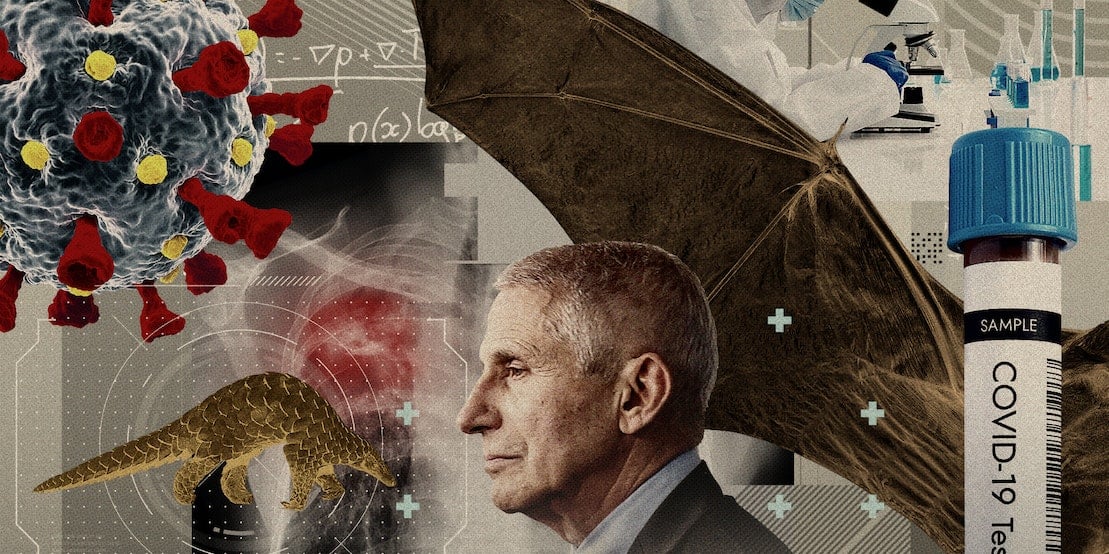

Quammen ends his story on an ambiguous note. SARS-CoV-2 likely had no single origin. Zoonosis is not a whodunit, it turns out, but, as one of his sources wrote, a “permanent process of evolution, adaptation and selection.” The virus appears to have spilled over into humans in two independent instances, probably originating in bats and infecting some unfortunate intermediary species that had the bad luck to be captured and sold in the wild game section of the Huanan wholesale market in Wuhan. “The scientists can tell us a lot,” Quammen writes, “but they can’t tell us everything.” Knowledge is always fragmentary and provisional. One day, if we’re lucky, we’ll learn more.

Indeed, in science, as in writing, what gets left out makes up more than half of any story. Most of the work is separating signal from noise, and determining which counts as which. For someone so skilled at the narrative arts, at the manifold forms of sleight of hand that turn dull facts into an engaging yarn, Quammen is oddly dismissive of any explanation that can be deemed “merely a narrative.” He insists on verbatim quotes—no tidying sources’ grammar for flow—because, he writes, “I share scientists’ respect for the sanctity of data.” He tries hard to be rigorous and, when he can be, is honest about what he’s jumping over, whether it’s the difference between an RT-PCR and an ELISA test (“Let’s skip that explanation and move on.”) or the manifold malfeasances and social inequities that caused so many unnecessary deaths: “those are topics for other books.”