When the first lockdown began last year, and the wider world bewailed the dramatically constricted life we were all being forced to lead, Conor O’Brien quietly marvelled at the strangely good timing of the whole thing for him personally.

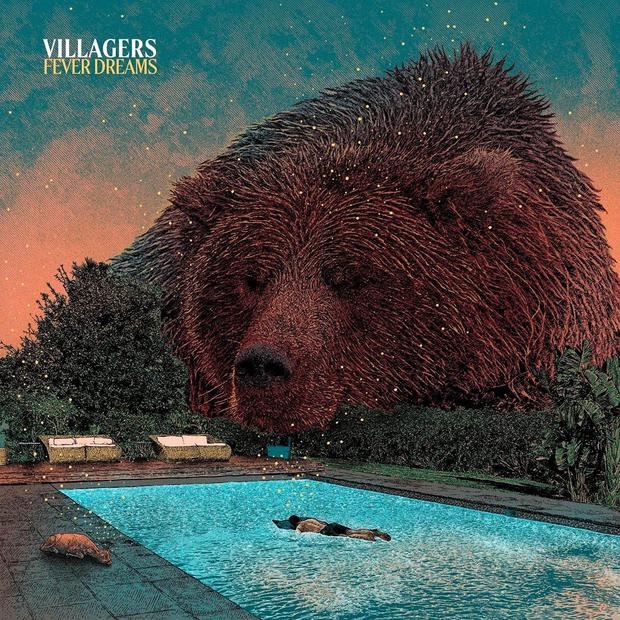

he creative force behind Villagers already had the bones of a new album and was anyway about to enter his own self-imposed lockdown, in which he could devote himself totally to the music. “I remember when [the pandemic] began, there was a meme going around that said ‘check in on your extrovert friends’,” he tells Review. “I’m not an extrovert and in a way the forced time alone really suited me. I understand the creative power of solitude.”

Ironically, Fever Dreams, Villagers’ new record, had already been his most collaborative work in years. The last day of actual recording was the first day of lockdown. “Last time [on 2018’s The Art of Pretending to Swim] I was doing it all by myself and I wanted to not do that this time around,” he explains. “We had four band sessions and each of them lasted maybe four or five days.

“Each time I would take home what we’d done and I would work on it at home, so it was very back and forth. You need quite a lot of trust. I’d toured with them, so we were able to be quite rude, when that was needed, and say exactly what we’d felt.” And the record, which he painstakingly worked on over the long months of lockdown, “was a good distraction from everything else that was going on”.

And the record is a move away from what he calls “narrative, thematic” songs and into music that is more “sensation based”. The lead single, The First Day, builds like a surge of joyous optimism and, more broadly, the album is a kind of paean to the real human connection that we lost as we migrated from real life to endless screens. “I feel the internet age is changing the way we’re thinking quite profoundly,” he says. “Our concentrations spans, the way we connect, the way we consume art, it’s had an impact on all of us.”

He connects the loneliness of our endless doom-scrolling with the power of the tech companies that profit from it.

“We’re living through this strange time, where, because of the pandemic, we’re even more on our screens, and corporations benefit from that. I’ve had some pretty two-dimensional conversations online on various different apps. I think that there’s something weird happening to our brains which we’ll only understand in about 50 years, a little like the way we look back at classic ads about housewives, and it will all seem a little ridiculous to us how much we allowed our minds to be destroyed.”

Solace in reading

So is there a solution for this distraction addiction? “I can only really speak for myself but I’ve found a lot of strength and solace in reading books that were written before the internet was invented. I think music, art and literature saved my brain.”

Growing up, the solitude and the solace of art were survival tools for O’Brien. He was raised in relative privilege in Glenageary, Co Dublin — his father is an architect and Conor went to St Conleth’s College in Ballsbridge.

“There was a lot of entitlement and new cars,” he recalls, but there was also a healthy smattering of ‘weirdos’ to make friends with. As the youngest by quite a distance in the family, he absorbed much of the music of his older siblings — the Kinks, Pink Floyd and Jimi Hendrix. “I was extremely happy until puberty hit and then I was miserable. I was always very into doing creative things for long periods of time on my own. I met a friend of mine, who’d grown up with me, and he said to me, ‘Where did you go?’ He said, ‘When you hit 13 or 14, we just never saw you any more’.”

O’Brien was off by himself, drawing and making music. “I was already experimenting with layering sounds by putting two cassette players beside each other, and music was all I thought about in school. I went to piano lessons when I was nine or 10 and gave them up when I was 12 or 13. My brother showed me how to play chords on a guitar and I quickly realised that it was all I wanted to do. I was top of the class until I was around 12 and then I started dropping down. I fell asleep a lot in school, because I felt I was just waiting to leave.”

It was Celtic Tiger Ireland and in Irish music terms, the era of the boy band. “It was kind of hell but I don’t want to overdramatise it. I’ve always had a handful of close friends and I felt very disconnected from the majority of my peers, but it fed into my creativity because it gave me a lot of time on my own and a bit of a break from that Celtic Tiger bubble that we were all in at that time.”

He came out to his first girlfriend when he was 17, and “she was great about it” — he is still close to her — but he didn’t feel any greater connection with the gay culture that awaited him than he had with his peers in school.

“I’m not really your average gay man, I can take or leave it a lot of the time. I’ve had quite long relationships in my life, but through all that I didn’t feel a huge amount of connection with gay culture. I’ve often found myself in a gay bar thinking, why is the music so shit? I’ve never been very scene-y so when I did come out, I felt like I was just telling people my biological reality.”

He formed his first band, The Immediate, while still studying for a degree in English and sociology, and they quickly gained critical notice — their first single was played on BBC Radio One and the Irish Independent’s music critic John Meagher named their debut (and only) album, In Towers and Clouds, one of the best of the 2000s.

Despite all this, O’Brien says: “It felt like the narrative of success wasn’t very true for us.

“We had no money for one thing. To keep something on the road when there are four of you, it was a lot of hard work. Once we started doing things like the Meteor Awards where we were miming, we thought this is not what we got into it for. We were more suited to NCAD college balls at 3am.”

Amid some bereavements, the band broke up and he began touring with Cathy Davey as her guitarist. “That was really formative for me. I was writing Villagers stuff during that tour and I was being exposed to musicians who had actually studied music. I knew I was in it [music] for the long run then.”

Villagers, which he formed in 2008, quickly became a sensation. Their emotional folk-pop, and O’Brien’s tender, almost conspiratorial vocals, made them a favourite with other artists — they supported Neil Young and Tracy Chapman even before the release of their debut album Becoming a Jackal, and by the time it came out, in 2010, the buzz had built to fever pitch.

They appeared on Jools Holland’s show, played the Meltdown in London, and the album, which was shortlisted for the Mercury Prize, quickly shot to the top of the charts here. O’Brien’s publicist once referred to him as an “artist’s artist”, he says, and one of the most gratifying things of the success that followed over the next decade, was the way in which his heroes — particularly Elvis Costello and Ed O’Brien from Radiohead — encouraged him.

Musical voice of social change

His 2015 album Darling Arithmetic dealt with issues like sexuality and homophobia. In the run up to the following year’s marriage referendum, he was cast as the musical voice of social change in Ireland. He’s still staunchly pro-marriage equality but says that, latterly, he has gained a certain respect for those who have a different view.

“At the time there was an older person I knew and he was voicing his opinions and in my head I was kind of cancelling him and thinking I could never speak to him again. But, in a way, now, I think he is from a completely different generation and only ever saw marriage as between a man and a woman and I have to respect where he is coming from because it’s just another cultural idea.”

He started doing cognitive behavioural therapy a few years ago but says that he didn’t find it especially helpful and agreed with a friend who referred to it as “a crutch”. “I think art and creativity are more holistic and go deeper than modern forms of therapy.”

He is excited for people to hear the new album, and though he says he shies away from trying to explain the songs, he’s gratified when he realises that his influences and inspirations inspire the listener. “The thing I really love about making music is when I realise that someone has had to do a bit of intellectual work in enjoying it. I don’t make music because I have the answers. People have to find those out for themselves.”

‘Fever Dreams’ will be released on Domino on August 20. ‘The First Day’ is out now