For the last 30 years, London’s Open House Festival has facilitated sneaky peeks at places of architectural interest, usually off limits. This year, Open House 2021 (until 12 September) is doing something counterintuitive, celebrating a more accessible distraction with a new architecture book – Public House: A Cultural and Social History of the London Pub.

Pubs might seem a curious site of interest for the festival, given they offer a warm welcome (and warm beer) any time of the year, but London’s pubs – from alehouses, coaching inns, taverns and gin palaces to theatre pubs, gay pubs, gastro pubs, tired old boozers and revamped crowd pullers – have been at the heart of the city’s cultural life for centuries.

When the Open House Festival launched in the early 1990s, pubs were playing a central role in London’s cultural and sub-cultural re-awakening. Indeed, you can argue that the city’s re-emergence as global cultural hotspot was haphazardly plotted in public houses. It’s impossible to talk about BritArt-era Shoreditch and Spitalfields and not mention the Bricklayer’s Arms or the Golden Heart; BritPop-era Camden and not talk about riotous goings on in the Good Mixer; neo-bohemian Soho and not wax loquacious about the French House and the Coach & Horses; or track London’s explosion as a foodie capital and not mark the Eagle in Clerkenwell as ground zero.

The cover of Open House’s book on London pubs, Public House

Three decades on, though, all is not well with the London pub. It’s not exactly last orders but the days when they functioned as geo-cultural landmarks seems to be over. The rise of the new-model member’s bar – first Groucho’s in the 1980s and later the Soho House chain – privatised boozy celeb shenanigans. The pub’s very publicness was suddenly a liability and private was cool. At the same time, there was a rise in dive bars, cocktails bars, faux speakeasies and the increasingly popular a-bit-like-a-bar-in-New-York bar. Defiantly not pubs.

And then came Netflix and Deliveroo and staying in became the new going out. An increasingly precarious business, the pandemic has threatened the liquidity of many pub operators, large and small (not that you would guess that on a booze-assisted crawl through Hackney, one of the few areas in the country where pub openings outstrip closures).

London pubs: a call to action

Public House, then, is both a lament and a call to action. A preface by London Mayor Sadiq Khan celebrates the London pub as a place of both community and resistance and calls for a communal effort to ensure their survival. The book’s editors Cristina Monteiro and David Knight are part of DK-CM, an architecture and planning practice that primarily works on the design of public buildings and public spaces.

They began documenting London’s pubs ten years ago while teaching architecture at Kingston University School of Arts, trying to work out how and why the best pubs, the ‘local’, worked as social spaces, as places ‘owned’, spiritually if not legally, by their customers.

The Dodo Micropub in Ealing

They also looked at ways they might be protected from rampant developers who saw more value in pubs when they were chopped up into apartments or, worse, flattened. (Westminster Council’s insistence that the developers CTLX rebuild, brick by brick, the Carlton in Maida Vale, a pub they had demolished without permission, was a useful cautionary tale. But, as Monteiro and Knight explain, while it is now relatively easy to protect a pub as piece of important local architecture, it’s harder to protect its purpose, its social value.)

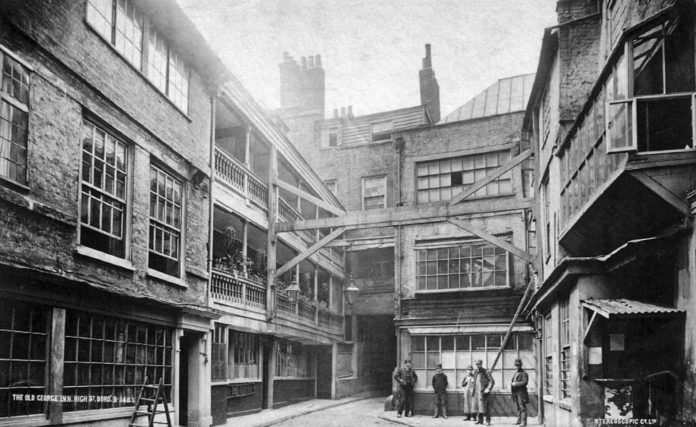

Their book celebrates 120 pubs of interest across London’s 33 boroughs (including National Trust-owned coaching inn the George, in Southwark, which is offering behind-the-scenes tours during the festival).

There is much here for the architecture buff. The archetypal London pub is, of course, Victorian, once divided into saloon and bar, but pub architecture is rich, varied and in a state of constant renewal. As the authors say: ‘The pub has experienced extraordinary transformation and reimagination – reflecting and sometimes shaping wider social and cultural changes. Pub types have merged, disappeared, hybridised, evolved, rebooted and generally got incredibly and delightfully confused over the centuries.’

Public House, though, is not an architecture guide, and certainly not a ‘best of’ listing (some of the pubs listed no longer exist), but a kind of social geography and history. Each pub entry has a date attached, a moment when it was most alive, interesting and what happened there instructive of wider goings on. The entries are accompanied by vignettes written by journalists, musicians, architects, comedians, artists and even politicians.

Postcard showing the The Spaniard’s Inn in north London

The authors are fascinated with pubs as places not just of community, but of collectivism. They are interested in them as buildings that constantly adapt and shift with trends and that are somehow spaces of performance and show, of debate and conversation, but also of domestic comfort and security, a place between private and public realm. They are, they argue, worth protecting and supporting, not as artefacts, but as vital social space.

And as they say, there are causes for optimism. Threats to close pubs have generated protests and birthed crowdfunding campaigns. Pubs that were in fact rather neglected have been rejuvenated. The threat of closure has inspired initiative and innovation and perhaps reminded communities of what might have been lost. Small independent breweries – and east London is awash with them – have started to take over and even open new pubs. There are now micro-pubs and even community-owned pubs.

The pandemic has encouraged most of us to re-examine the value of our social life and social spaces, and with them, the intrinsic value of the pub. Remote and hybrid work may actually encourage a revival of the local, a ‘third place’ away from the laptop, the Zoom zone and AirPod earache, a place for IRL conversation and distraction, of actual likes and LOLs. And warm beer.

Activist Sylvia Pankhurst in the Gunmakers Arms, which was taken over in 1915 by Pankhurst and her suffragettes for use as a day nursery and renamed as The Mothers Arms

Our pick of London pubs

Has all this recounting of the rich and diverse history of pubs left you thirsty for more? Here is our pick of London pubs from Public House to try; venues with a strong personality, architectural interest and a well-maintained, authentic feel.

- The Seven Stars, Holborn (WC2A 2JB)

Artfully ramshackle 17th-century alehouse, it was bought by new-model landlady and cook Roxy Beaujolais in 2001. Her husband, the architect Nathan Silver (co-author with Charles Jencks of Adhocism), redesigned the interiors, not that you’d really notice.

- The Fox and Anchor, Smithfields (EC1M 6AA)

Once an early opener serving the butchers of the nearby meat market, the Fox and Anchor features a tiled, Art Nouveau exterior and private wooden booths on the inside.

- The Atlas, Fulham (SW6 1RX)

Wonderfully intact 1930s Truman Brewery interiors

- The Queen Adelaide, Hackney (E2 9ED)

Shoreditch’s George & Dragon had been an ephemera-stuffed celebration of queer nightlife for 13 years when it closed in 2015. Luckily its managers quickly found a new home deeper into Hackney at the Queen Adelaide and took their ephemera and devoted revellers with them.

- The Golden Anchor, Nunhead (SE15 2DX)

A long-time favourite of south London’s Caribbean and British-Caribbean community, The Golden Anchor has been run by the indomitable Lana Bewry since 1998 and offers a Jerk-accented menu, runs open mic nights and is a popular spot for devoted dominoes players.

- The Shakespeare’s Head, Islington (EC1R 1XA)

A tiny red-brick box just round the corner from Sadler’s Wells theatre. Built in the early 1960s with an interior that has changed little since.

- The Little Green Dragon, Winchmore Hill (N21 2AD)

In 2015 the original Green Dragon became a supermarket. Within two years, the small but lovingly formed Little Green Dragon micro-pub had opened nearby.§