“The rent is too damn high.”

That adage sums up a major reason Los Angeles educators feel burned — and priced — out. A recent report from the local teachers union lists unaffordable housing, large class sizes and over testing of students as contributors to teacher stress. As the nation contends with a teacher shortage that, in some regions, has been exacerbated by book bans, parental rights bills and anti-LGBTQ+ laws, educators in locations with greater academic freedom still have challenges.

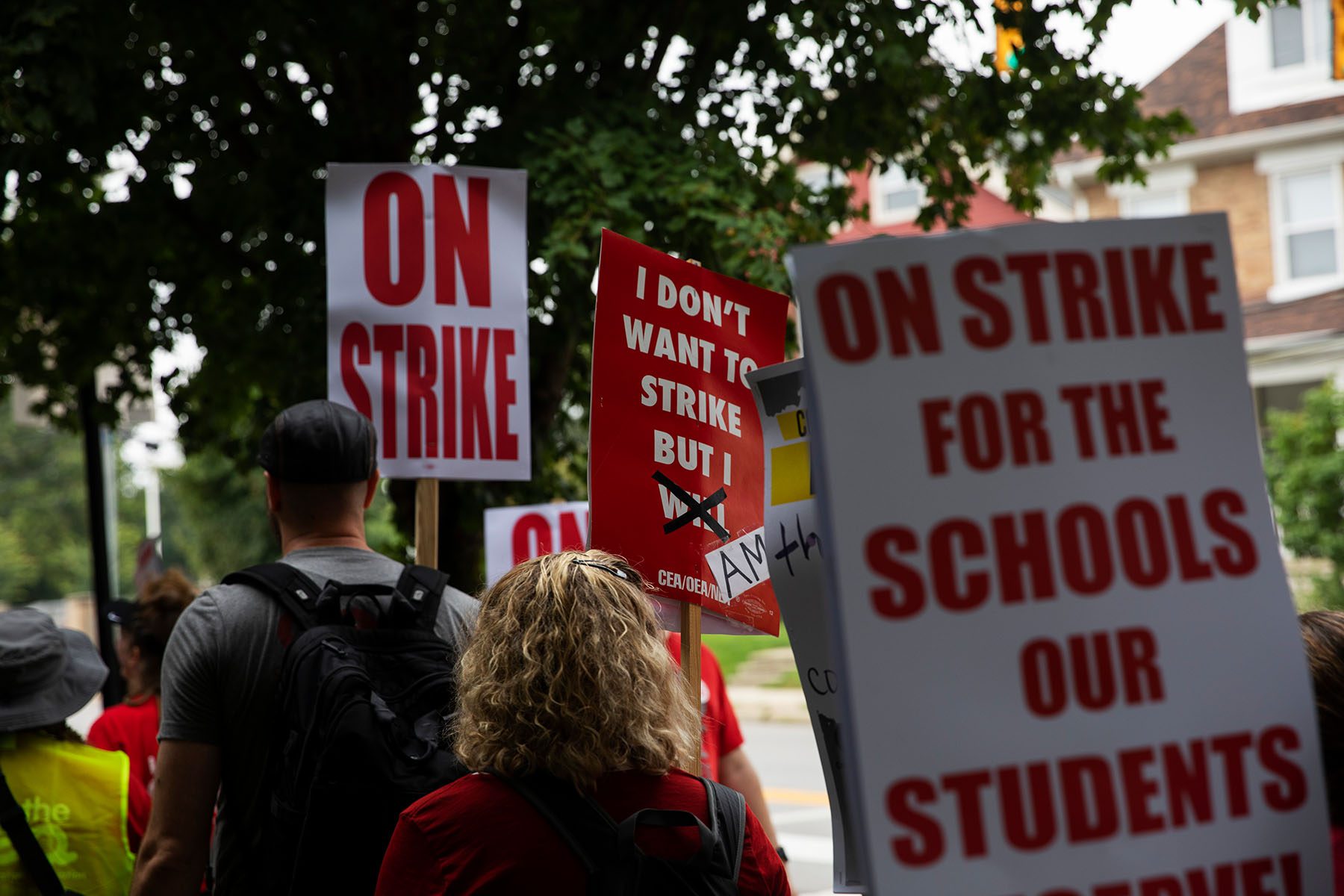

This year, a series of teacher strikes occurred in Democratic-led cities including Minneapolis, Sacramento, Seattle and Columbus, where teachers said they were striking to draw attention to their financial hardships and the additional supports students need. Teachers in the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD) have similar concerns, with 70 percent contemplating leaving the profession entirely, according to the study “Burned Out, Priced Out: Solutions to the Teacher Shortage.”

Released last month, the report from United Teachers Los Angeles (UTLA) draws on data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the California Commission on Teacher Certification, and a survey of more than 13,000 educators to identify the primary factors affecting teacher well-being. Their worries are largely economic: Uncompetitive pay not only makes it difficult to afford housing but has also resulted in more than a quarter of UTLA members working a second job to make ends meet, the study determined.

The financial challenges teachers encounter are often even more dire for students and their families, for whom homelessness is a pressing problem, UTLA noted. Given the grim financial realities that accompany life in one of the nation’s most expensive cities, the union recommends that the school district use its resources to support the emotional and economic needs of students and staff alike.

- Read Next:

“Our educators are one of the most educated workforces in the country, and a large percentage of those educators not only have college degrees but also obtain [postgraduate] degrees and certifications,” UTLA President Cecily Myart-Cruz told The 19th. “But our profession takes a wage penalty in comparison to other professions with similar requirements.”

Over the past five years, the average LAUSD teacher earned between $74,000 and $79,000 annually, compared to a salary range of $94,000 to $101,000 for the average bachelor’s degree-holder in Los Angeles, the UTLA study found. Teacher salaries don’t reflect the rate of inflation, the report contends, a conclusion that a recent study from the Economic Policy Institute (EPI) also makes. The EPI analysis found that teachers nationwide earn 23.5 percent less than comparable college graduates, while the UTLA study found that its members earned 22 percent less than similarly educated Angelenos during the 2019-20 school year. To make up for this deficit, 28 percent of UTLA educators work another job to supplement their income, with 24.4 percent of teachers who’ve worked for the district for more than 20 years doing so.

“Los Angeles Unified acknowledges that economic conditions, including insufficient pay, critical hardships and the COVID-19 pandemic, have complicated teacher recruitment nationwide,” a district spokesperson said in a statement to The 19th.

The district did not discuss efforts it has made to retain veteran teachers such as Anthony Colla, a language and literature teacher at Eagle Rock Junior/Senior High in Northeast Los Angeles. He’s taught for LAUSD for 17 years and pads his income by teaching summer school and working 20 hours per week with the education consulting firm he started nearly 10 years ago.

“I have two master’s degrees, and I’m still paying student loans,” he explained. His side gig gives him a 30 percent income bump. As a veteran teacher, he’s near the top of LAUSD’s salary schedule, he said, but his net pay is about $5,000 monthly. He’s grateful that he purchased his home 26 years ago, otherwise paying for housing would be a challenge.

“If I had to pay the $4,000 market value rent for the property I live in — I own my home — I would not be able to afford it at all,” he said.

First-year LAUSD teachers make $51,440, according to the UTLA study, which cites a June 2021 district finding that there’s no Los Angeles neighborhood where early career educators can live without being rent-burdened. According to the federal Brooke Amendment, which revised public housing guidelines in 1969, tenants should not spend more than 30 percent of their income on housing. This isn’t possible for most UTLA educators, two-thirds of whom report being unable to afford housing in the neighborhoods where they teach.

“It’s huge,” said Pedro Noguera, dean of the Rossier School of Education at the University of Southern California. “And it’s not just teachers. It’s police officers, firemen, all the clerical workers, custodians — if you are not fairly affluent, you can’t afford to live in L.A. And rents continue to rise, so you literally have teachers and secretaries and receptionists who commute … way over an hour each way to work. And that adds to the stress because then you start to say, ‘Is it worth it to travel this far for a job that is paying so little?’”

The district has collaborated with developers on three affordable housing projects to enable employees to live in the communities where they work. Last year, it announced that a similar effort was underway to work with developers to build affordable-housing properties where LAUSD personnel would be prioritized as tenants.

“Los Angeles Unified is broadening our partnerships to develop new opportunities for families and employees, which directly target housing affordability, working conditions and benefit packages,” a district spokesperson told The 19th. “The district remains committed to leveraging all resources to strengthen school communities.”

That teachers struggle to afford housing indicates that teachers aren’t being paid what they’re worth, said Myart-Cruz. A number of educators she’s encountered supplement their income with gig economy jobs, working for companies such as DoorDash and Instacart during their off hours. In March, Airbnb announced a partnership with the National Education Association to help teachers serve as hosts and boost their wages, but the collaboration did not move forward. Still, teachers earned more than $276 million from hosting on Airbnb in 2021, the company announced in August.

“It’s ridiculous. It’s shameful,” Myart-Cruz said of teachers having to take on additional work to raise their wages. “And not only that — folks have to grade papers. When do folks have that opportunity?”

Another source of stress for teachers is the series of standardized tests they’re required to give each year. These tests limit the autonomy of teachers and overwhelm students, who take at least 100 standardized assessments by the time they reach sixth grade, the UTLA report states. UTLA wants the district to eliminate all standardized assessments that have not been government-mandated.

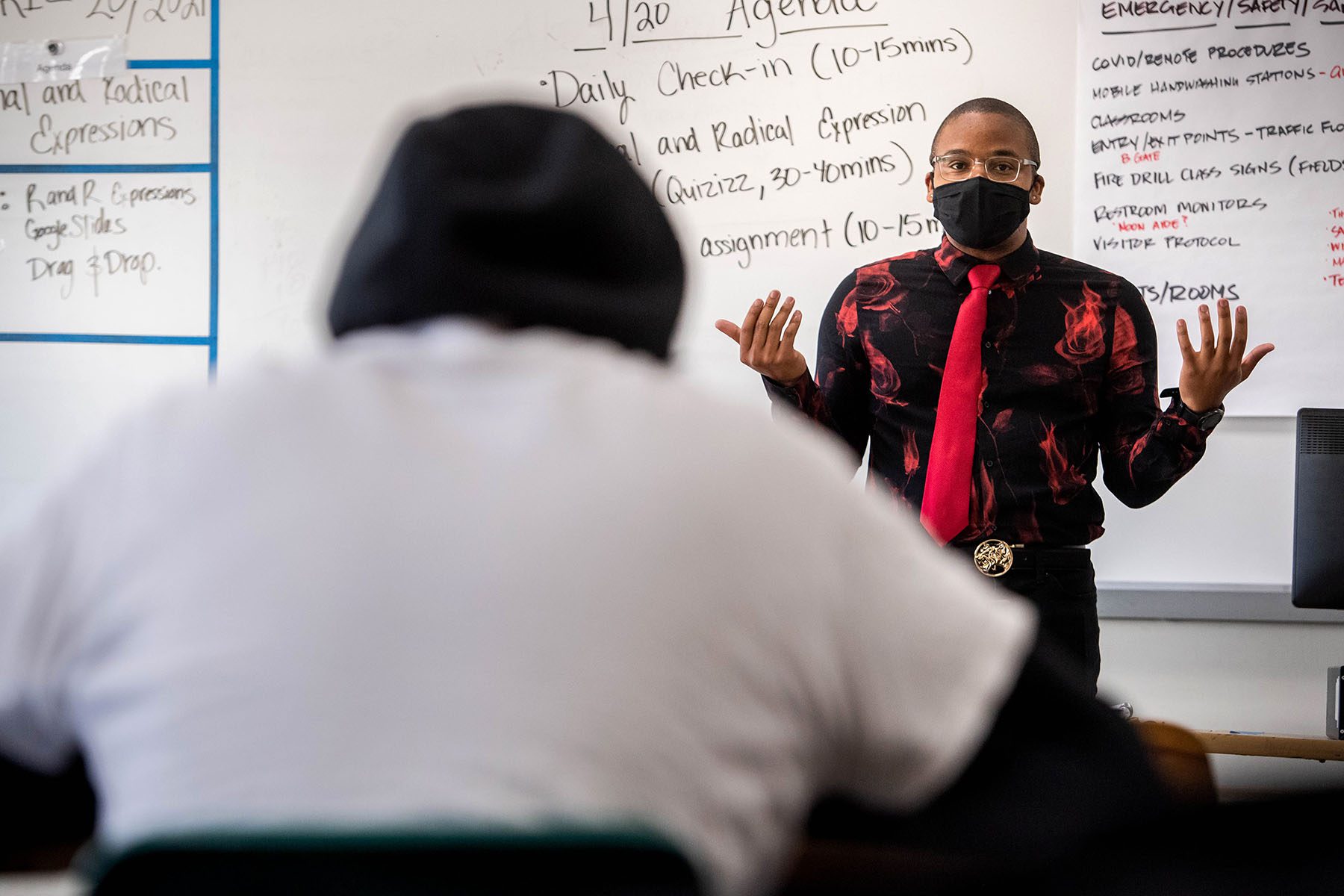

“You need to assess kids to see how well they’re doing,” Noguera said. “But…I think what’s happened in many districts is they put too much emphasis on assessment and not enough emphasis on instruction. How do you make sure that kids are getting high quality instruction and the supports they need? So the teachers are probably right to push back on the amount of assessment that the district requires — not the state.”

Colla estimates that he loses two weeks of instructional time to testing each school year. He said the process has become normalized for his students. As an experienced educator, however, he takes issue with the amount of standardized tests he has to administer.

“Especially when you look at what it is precisely that the [test] is measuring, all these standardized tests … are measuring things which may or may not have any real bearing on how well the students are doing,” Colla said.

During a year when teachers in urban and suburban districts alike have engaged in walkouts, Myart-Cruz isn’t ruling out a labor action but called talk of a strike “premature.”

“But let’s be clear that we stand ready to have the conversations with our members about respect,” she said. “Our educators did a yeoman’s job in this pandemic, flipping their entire lives, their entire curriculum to a platform they didn’t even know themselves. First they got applauded for doing a yeoman’s job and then they got lambasted for not coming back sooner. Our educators did that, held it together, and they should be paid what they’re worth.”

Colla said that teaching online during the pandemic was his most difficult period as an educator. His struggles haven’t ended now that school is back in person for the second consecutive school year. Students still have learning deficits, and he can’t access all of the digital learning tools he needs due to a recent ransomware attack on the district. The recent political attacks on teachers nationwide haven’t helped his mental health either, particularly because he identifies as queer.

“It doesn’t affect me directly,” he said of laws such as Florida’s “Don’t Say Gay.” “But it affects me indirectly because it’s a continuing move in this country to denigrate educators, to make teachers the bad guy, the fall guy, the straw man. It’s a pseudo-intellectual movement where one person’s completely uneducated opinion is considered just as valid as another highly educated individual’s position, and that’s simply not true. The whole move towards ‘Don’t Say Gay’ and banning books — we know what kind of governments ban books. The governments that ban books are fascist.”

In some parts of the country, restrictions on what educators can say in class or teach have prompted them to leave the education profession entirely.

“Across the country, teachers are feeling stressed out from the lingering effects of the pandemic just like a lot of kids, so we have seen mental health challenges amongst teachers, rising depression, anxiety, and the school shootings have made it worse,” Noguera said. “Then you have the politics of the moment … All of that is adding to the pressures on teachers and making many question whether or not they want to continue teaching.”

As conservative lawmakers limit what students can read and educators can teach, UTLA is pushing for its progressive policies to become realities in LAUSD. Educators should be able to afford housing where they teach, Myart-Cruz said.

“We have 86 pages worth of proposals, and all of them are righteous,” she said. “But we also need people to have some gumption to do the necessary things to make sure that our kids have holistic learning environments.”

*Nadra Nittle is married to an LAUSD teacher and UTLA member.