Feeling like you have to choose between your identity of race or sexuality, not knowing who you are, and the immense pressure of being a first-generation immigrant child. These are just some of the topics discussed at the “Brown and Gay in L.A.” event last week.

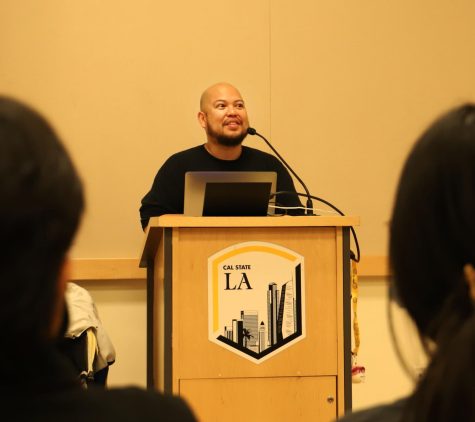

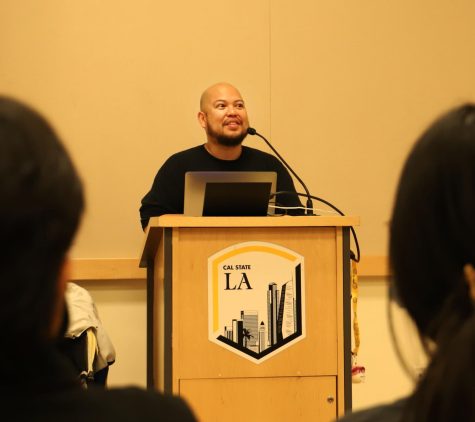

Anthony Ocampo, the author of “Brown and Gay in L.A.: The Lives of Immigrant Sons,” spoke at the Cal State LA campus on Thursday, Oct. 20. Ocampo is a son of Filipino immigrants, who identifies as gay and is from Northeast Los Angeles. He teaches at Cal Poly Pomona in the Department of Sociology and directs the new Office of Ethnic Studies.

This is Ocampo’s second novel, one which was inspired by the stories he felt were left out of his first book, “The Latinos of Asia: How Filipino Americans Break the Rules of Race.” Ocampo came to campus previously to discuss this first novel.

“I feel like the folks at Cal States, there’s not a lot of hand holding,” Ocampo said. “You all have your unique perspectives and add to the conversation. I think Cal State LA is more reflective of our country. I feel like I’m in a time machine of what our future will look like.”

“Brown and Gay” tackles how Asian American and Latin American sons of immigrants navigated their queerness and brownness while growing up, according to Ocampo. The intersection of race, sexuality, and femininity, as well as navigating how to be a person of color within queer spaces and vice versa, are some of the key themes of the novel.

“A lot of my research and the work that I do in sociology is shaped by my identity as a queer Filipino American,” Ocampo said. “I do a lot of my research, and I teach a lot about the experiences of folks who are part of the immigrant generation. In other words, folks whose parents were born in a different country.”

As the book title suggests, intersectionality is a huge theme of the novel and the event discussion.

“For folks who are also LGBT, it was almost as if you’re grappling between this thing of like, am I a queer person? Or am I a Filipino? So for a lot of folks, it’s caused a lot of angst to try to navigate between who they were,” Ocampo said. “For a lot of folks, it almost felt like your ethnic or racial identity can’t match up with your sexuality and sexual identity. In other words, folks felt like if they’re Latino, they can’t be queer, or if they’re Filipino, they can’t be gay.”

The most significant point Ocampo presented to audience members was how boys of color he interviewed often tried to excel academically to “make up” for being gay.

Asian American men often benefit from the stereotype that Asian people are somehow inherently smarter and excel in school. For Latino men, Ocampo found that the opposite was true. Ocampo said that one story in the novel is of a Latino man who was seen as a rarity because he excelled in school and was Latino. This also made him feel isolated from the Latine community.

Ocampo called this “covering,” and it is seen as distracting people with education. Ocampo was told multiple times that men would rather have been “the smart kid” than “the gay kid.” While this can benefit some queer people of color individually, such as some of the Asian men Ocampo spoke with, it is overall detrimental.

Attendee Dominic Javonillo, who uses he and they pronouns, related heavily to this.

“When he was talking about the experiences of being Filipino American and gay and having to cover using academics, it was like he was reading me,” said Javonillo, a UC Irvine Ph.D. student. “When I’m applying to things, usually with personal statements, I always have to define my identities and why that matters.”

“Reading” is a slang word meaning calling someone out, usually for their flaws.

“I think Filipinos, especially queer Filipinos, have such a disconnected relationship with boxes,” they said. “Whether we’re Asian American or not, whether we’re straight or queer, it was just this interesting intersection of not really fitting into any sort of broad category and having to go through an institution like college or grad school that pretty much boxes you in.”

Over 15 people attended the event. At least half said they were first-generation. Many said they related to what Ocampo said about many first-generation children feeling a lot of pressure to be perfect.

Audience member and Cal State LA student, Kerlyn Garcia, was one of them. She said she often found herself doing anything and everything to impress her parents and be perfect.

“I initially came just for my Filipino class, but the reason why I chose this material to go into is because I recently realized a lot of stuff about my sexuality and I’m Filipina,” Garcia said. “There was a lot that I still have to figure out and I went here in terms of trying to find more information and how I can identify myself, because that’s the hardest part of being yourself.”

This event was put on by the Asian Pacific Islander Student Resource Center (APISRC) and the Gender and Sexuality Resource Center.

“October being Filipino American History Month as well as LGBT History Month, it just seems fitting,” said Anh Le, APISRC coordinator. “We met Dr. Ocampo at a conference called the National Conference of Race and Equity, where he talked about this book. It is very fitting for our space, the center’s mission and values and it just so happens that he embodies both identities celebrated this month.”

Le said the Cross Culture Center, which houses both departments, is a firm believer in intersectionality.

“It can’t be siloed, like just because you’re gay, you’re in this center or just because you’re Asian, you’re at this center,” she said. “So it’s our job to bridge those gaps for our communities.”

Ocampo said his next book will be about Asian Americans and the criminal justice system. He was inspired to do so after reporting on a Buzzfeed article on the topic.