Eight hours before Brockhampton’s new album goes live, frontman Kevin Abstract’s phone rings with a FaceTime call from his friend Jaden Smith.

The actor-musician (and son of Will and Jada) is reaching out to congratulate the members of this 13-man Los Angeles rap group — most of whom are sprawled on a U-shaped sofa in Abstract’s Hidden Hills living room — on the release of “Roadrunner: New Light, New Machine,” a vivid and assured collection that wraps searing personal confessions in sumptuous pop hooks and rowdy hip-hop grooves.

“I’m so ready to lose my mind to this album right now,” Smith says as Abstract angles the phone so everyone can see. “And you guys are dropping at the perfect time. N— are getting vaccinated, things are about to open,” he adds.

“Y’all are gonna tear s— up, bro.”

Brockhampton’s sixth studio LP in a whirlwind four years, “Roadrunner” follows the breakout success of “Sugar,” the tender and silky 2019 single that took off on TikTok before finding its way to the Billboard Hot 100 and to a high-profile remix featuring Dua Lipa. The song, which has been streamed more than 300 million times on Spotify, introduced countless listeners to a self-described boy band whose proudly diverse lineup — among its rappers, producers and visual artists are Black, white, straight and gay men — gives it the air of a Gen Z dream team.

Now, as the group’s famous pal suggests, “Roadrunner” is poised to deepen that mainstream impact with sharp-edged bangers like “Buzzcut” and summery bops like “Count on Me,” the latter of which arrives accompanied by a splashy music video starring Lil Nas X and Dominic Fike as lovers on a psychedelic journey.

So why on earth is Abstract telling people that Brockhampton isn’t long for this world?

“You just got to know when to let go,” says the soft-spoken 24-year-old, who recently tweeted, “2 brockhampton albums in 2021 — these will be our last.” Dressed in cozy athleisure wear, his hair dyed like a rainbow snow cone, Abstract is hanging with eight of his bandmates — Romil Hemnani, Merlyn Wood, Joba, Matt Champion, Dom McLennon, Bearface, Jabari Manwa and Kiko Merley, all in their mid- to late 20s — on a sunny afternoon at his rambling yet minimally furnished home on a bucolic residential street. (The group’s remaining members, who handle nonmusical endeavors like photography and Brockhampton’s digital presence, are Henock Sileshi, Robert Ontenient, Jon Nunes and Ashlan Grey.)

“Roadrunner” was to hit streaming services that night, and the next day, Brockhampton was to perform in a ticketed livestream from producer Rick Rubin’s Shangri-La studio in Malibu. Rubin, whom Hemnani refers to as the group’s “Jedi master,” is one of several older admirers, along with Spike Jonze and the RZA, who complement Brockhampton’s mostly teenage and twentysomething audience.

At the moment, though, the members are picking at delivery containers from McDonald’s and Veggie Grill as Abstract explains that, timing be damned, he wants to “leave the group alone” to free everyone “to explore their own thing.”

For Abstract, one of hip-hop’s few artists out as gay, that means directing videos and running his label, Video Store, as well as doing solo records. Watching Lil Nas X’s “Montero” go to No. 1 this month — despite (or more likely because of) a controversial clip in which the rapper gives the devil a lap dance — “was super inspiring to me,” Abstract says.

“I just want to make really big gay pop songs because of what he did.”

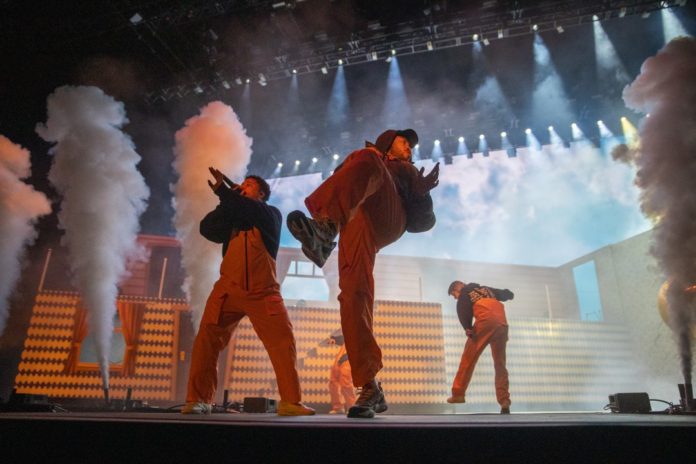

Brockhampton performs at the Camp Flog Gnaw Carnival in L.A. on Nov. 10, 2019.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

Yet you also get the sense that Brockhampton wouldn’t mind a break from the scrutiny that’s come with its success. In 2018, the group pushed out founding member Ameer Vann, whose face had appeared on the covers of all three volumes of 2017’s “Saturation” trilogy, after several women accused him of sexual misconduct. And now it’s facing questions about its association with actor Shia LaBeouf, whom Abstract described as a “mentor” before LaBeouf was accused late last year by his ex-girlfriend, musician FKA twigs, of a range of abuses.

No act would welcome the trouble these connections have created. But it’s especially uncomfortable for a group that talks about remaking the boy-band framework as a kind of safe space for inclusion and vulnerability.

Asked how it feels to be watched for signs that Brockhampton isn’t living up to its woke branding — “Is Brockhampton canceled?” reads one top Google query — the members go quiet before McLennon volunteers an answer.

“It’s like when you’re driving and the headlights pop up behind your car and you’re not sure if you’re being pulled over or it’s the person next to you,” he says.

“Facts,” Abstract adds in agreement.

Has it been painful to discover that people close to the band may not be who they appeared to be? Abstract sighs and says, “It’s painful,” before Bearface cuts him off.

“I think we should leave it at that,” Bearface says.

Increased attention is certainly what Brockhampton is looking to draw with “Roadrunner,” which features guest spots by Shawn Mendes and ASAP Rocky and delivers on the melodic potential that “Sugar” revealed.

“I’m trying to be like the Bee Gees, man — every part is a hook,” says Hemnani, who co-produced most of the album’s 13 tracks with Abstract and Manwa with occasional assists from outside collaborators such as Chad Hugo of the Neptunes.

Abstract points out that the group relies less these days on the pitch-shifting vocal effects it once favored, and indeed there’s an emotional clarity to the new material — be it the brooding “The Light,” in which the frontman admits, “I still struggle with telling my mom who I’m in love with,” or a breezy flirtation like “I’ll Take You On,” featuring R&B great Charlie Wilson — that contrasts with the willful murkiness of Brockhampton’s early stuff.

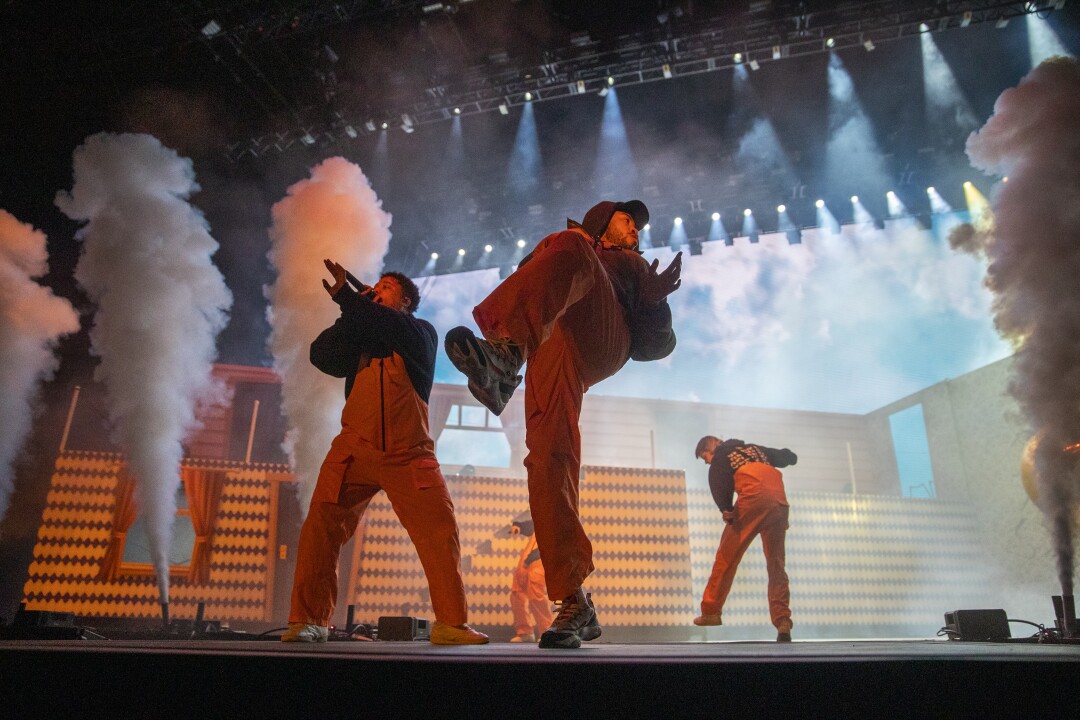

Brockhampton, from left: Jabari Manwa, Kevin Abstract, Kiko Merley, Bearface, Joba, Matt Champion, Romil Hemnani, Dom McLennon and Merlyn Wood.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times)

The group started around 2014 in Texas after Abstract (whose mates call him by his real name, Ian) asked the readers of a Kanye West message board if anyone wanted to start a band with him. Once assembled, the members of Brockhampton — so named after the street that Abstract grew up on — moved to L.A., where they lived together in a series of houses before scoring a multimillion-dollar deal with RCA Records and eventually scattering across town. Today the group is managed by Christian and Kelly Clancy, the married couple who also oversee the career of Tyler, the Creator; Peter Edge, RCA’s chairman and CEO, sees Abstract in “a lineage of multidisciplinary talents” including Donald Glover and Pharrell Williams.

In spite of the momentum provided by “Sugar,” the musicians say they struggled to get the ball rolling on “Roadrunner,” in part because the pandemic imposed a type of separation they’d never experienced. Yet inspiration finally arrived in the form of tragedy: Joba’s father’s death by suicide, which the musician describes in brutal, gripping detail in “The Light” and the album-closing “The Light Pt. II.”

“Those were the easiest songs I ever wrote,” says Joba (born Russell Boring), who in his verses ponders a complicated relationship with religion that also led Bearface (Ciarán McDonald) to write “Dear Lord,” a gorgeous close-harmony hymn with echoes of Boyz II Men and Bon Iver.

Asked if Brockhampton might secretly be a Christian rap group — even some of “Roadrunner’s” lighter tunes explore themes of faith and the search for meaning — the members smile and shake their heads.

“My family’s Hindu,” says Hemnani. Still, they acknowledge they’re drawn to topics beyond pop’s usual subject matter. “I don’t know if people wanted to hear a gospel album from Justin Bieber,” Hemnani adds of the latest from the former teen idol. (Turns out they did: “Justice” just logged a second week at No. 1.) “But I always appreciate someone who makes whatever they want even if it’s not what people wanted to hear.”

Abstract recognizes that writing about his life represents a challenge to the status quo. “Being queer in hip-hop’s always gonna be risky to a lot of people,” he says. What moved him about Lil Nas X’s “Montero” video was “seeing him be happy while being gay while being a Black man. It’s not a ‘Brokeback Mountain’ story where he’s sad. I think that’s easier for people to process: ‘Oh, it’s so unfortunate that you’re gay.’

“And I think we helped open the door for someone like him,” Abstract continues. “Before our first album, there weren’t many rappers being super stoked on being gay. But the way we talked about it was braggadocious in the way Lil Wayne is. That helps normalize it.”

At that, Hemnani pipes up: “Somebody told me the other day that your verse on ‘Star’” — lines about giving oral sex from the first “Saturation” LP — “was the first time they felt like being gay sounded cool,” he tells Abstract, which seems to leave the frontman unsure of how to respond.

“Yeah,” he says awkwardly after a few seconds, and that makes everybody laugh.

That capacity to change the way people think — particularly young people — is of obvious importance to Brockhampton. Yet when the conversation turns to why they value the opinions of Rubin and his more established ilk, Wood voices a surprisingly curmudgeonly point of view.

“Most youth culture is trash,” he says to immediate groans from the rest of the band. “Most of that s— is here today, gone tomorrow. People think the ’80s was so great. Nah, that’s 5 percent of what was on the charts in the ’80s.”

Wood’s point is that older people — “people with more mature taste,” as he puts it — have a longer view that makes them better equipped to gauge true quality. “They’re less fickle,” he says.

Wood goes on to insist that artists need to feel free to express unpopular opinions and sometimes to work through bad ideas to get to good ones. “How do you expect anybody to get anywhere if they don’t have the ability to go wrong?” he asks — a question often held out as a critique of so-called cancel culture.

But it’s not clear that everyone in Brockhampton shares his attitude.

“When you asked if we feel watched, nobody really wanted to answer because we know that whatever we say could get looked at negatively,” Abstract says. “So it got tense.”

According to the frontman, not much about the way they interact has changed in the years since they met, even as #MeToo and Black Lives Matter have triggered innumerable examinations of how race, gender and sexuality play out in organizations of every size.

Should anything be taken from the decision to use asterisks in place of the N-word in “Roadrunner’s” lyric sheet?

Abstract grins. “Oh, that’s just because the person that typed it out wasn’t Black,” he says.