In recent years, there has been a growing number of artistic ventures about the lives of LGBTQ+ people in Russia. One of them is the art project PASHA. Though he doesn’t reveal his real name or the details of his biography, the artist behind the project regularly publishes new works on Instagram under the handle @go_pasha_go. The account’s bio describes the author as an “Anonymous Artist. Born gay in the Soviet Union, living gay in Russia.” And his works range from collages of Soviet politicians and Disney characters alongside homophobic slurs, to anonymized self-portraits, and a combination “LGBT USSR” flag. Meduza sits down with the author of the art project PASHA to find out the story behind these works.

“I had the idea of making works about gay themes a long time ago. But I only made up my mind last year. Before that it was scary, and it was impossible to collect [my] scattered thoughts and ideas into something whole,” the author behind PASHA says to Meduza, when asked how the art project began.

As the artist explains, he gradually realized that he wanted to use his own personal experience as a starting point for conversations. “To talk about topics of bullying, homophobia, self-acceptance, as well as about [being] forced to wear masks and hide your real self,” he says. “In my case, the use of the body and sexual imagery is a means of drawing attention to more complex and important themes.”

The artist began sharing his creations on Instagram under the handle @go_pasha_go. The art project gained wider recognition after PASHA made the Center Stage initiative’s shortlist in the “Artists in early career stage” category in August 2020. Nevertheless, the author behind the project isn’t ready to reveal his identity “I don’t show my face. To a certain extent I’m lucky: I can be open with my family and friends. But I think it’s important for the project to maintain anonymity, at least at this stage,” he explains.

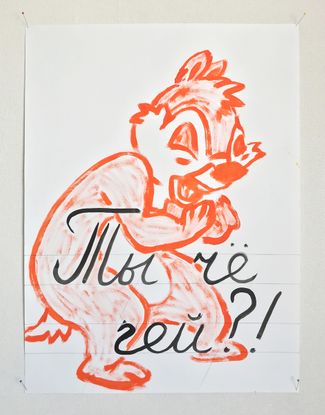

Despite the artist’s hidden identity, PASHA remains a deeply personal project. Its many works include a series of larger drawings and smaller graphics that incorporate well-known animated Disney characters, like Winnie-the-Pooh. These childhood images are displayed alongside anti-gay insults; words and phrases the artists “heard from his peers” back in the days when he used to watch Disney cartoons on TV. “These cartoons really helped me to cope with external aggression and were a form of escapism,” he recalls.

The art project also includes three series of portrait photographs inspired by homophobic name-calling and notes passed in school, titled “Pedik” (“Fag”), “Baba” (“Sissy”), and “Goluboy!” (“Blue!” — a slang term for a gay man). “I make them real, I turn into them. When I was a child it was painful and unpleasant, but now I can try these images on for myself, show that they’re stereotypes, I exaggerate them on purpose,” the artist explains. “On the one hand, a queer character with a hidden face is already a kind of stereotype. On the other hand, it’s a generalized image. I believe it’s easier to associate yourself or your friends with this. And to just think about this theme without ties to a specific person.”

At the same time, the artist underscores that the use of homophobic slurs in his works isn’t an attempt to rid these insults of their negative connotations or “reclaim” them for himself. “For me [‘fag’] always was and will remain an insult. I experienced very negative emotions when called that. And I don’t think I will ever be able to call myself that,” he tells Meduza.

One of the few biographical details the artist reveals is that he was “born gay in the Soviet Union.” Asked about what it was like to grapple with queer identity during this period, he says that he didn’t come across any “mainstream homoerotic literature” until he was at least 20 years old. “Before that there was nothing,” he recalls. “My understanding of myself took place without any information. I just observed myself and realized that I was different from my comrades, from my classmates. There was no word for this — and there was no Internet to look for this word or find information […] Everything happened on the level of feelings. I simply didn’t understand what it was.”

In preparation for the PASHA art project, the artist started gathering archival materials from when he was growing up to create “memory boxes” made up of “trinkets from childhood, clippings from newspaper and magazines from the 1980s.” These “snapshots” of the Soviet Union’s later years became a key components of the project. “For example, one of the works has a portrait of [Soviet leader Leonid] Brezhnev, under whom I was born,” the artist explains to Meduza. “These ‘boxes’ are mixed [with] what is happening with me now. There are photographs of me now and what happened when I was little. Somethings I recreated — for example, drawings I drew in school on the backs of lined notebooks. Or the notes that we passed to each other in school.”

In particular, the artist remembers being bullied in school for being different. “I played with dolls with my female friends. Not with the boys, of course, but when I went to visit my female friends. But for them [the boys] this meant that I wasn’t ‘one of them,’ but one of the girls,” he recalls. “And later, when I was in school in the 1980s, there was still a How can you be nice to people who are thrown in prison?”

After years of anti-gay bullying and “teenage experimenting,” the artist says he came to understand his sexuality “relatively late.” It wasn’t until the 1990s that he was able to access information about LGBTQ+ people, in publications like the cult glossy “Ptyuch” and the newspaper AIDS-Info. “I remember this feeling: you read and you feel that this is about you. And once this is written about, it’s not a pathology. And this means it’s not so bad, you aren’t alone, and you won’t necessarily end up in jail,” he tells Meduza. “In the nineties and the early aughts, there was a general feeling that all of this was starting to become the norm. Then everything changed again.”

Today, LGBTQ+ people are much more visible in Russian society — but only to a certain extent, the artist says: “I constantly remind myself that I’m in a bubble.”

“My feeling is that there was a much calmer period in the 1990s and early 2000s. Many people didn’t care [about other people’s sexual orientations],” he continues. “In general, a situation of equality and mutual respect seems ideal to me. [Where] no one divides anyone into groups and everyone lives together peacefully — with a certain kind of indifference. Of course, it sounds like some kind of utopia, but I know that such a thing is possible.”

Contrary to the artist’s hopes, the situation for LGBTQ+ people in Russia has become more difficult in recent years. He attributes this to a “wave of negativity in the media,” as well as the “gay propaganda” law introduced in 2013. The artist describes this legislation — banning the “promotion of non-traditional sexual relations” among minors — as “ridiculous.”

“In early childhood, without any propaganda and any information at all, I understood that I was different from most boys. And only later I read somewhere and found out that there are people like me. I found out I’m not alone,” he tells Meduza. “Then there was a definition, a name for who I am. After that [things] actually became much easier and calmer for me. I’m gay. Well, what can you do — okay.”