Prologue

Jack finishes dinner first and lays his folded napkin on the solid surface of our round oak table. How many times have I seen him do this? This man — my husband for more than forty years — hasn’t changed much from the young man I met when I was a college student in Norman, Oklahoma, in the sixties.

I know that everyone sees themselves at the center of their own stage, and every couple feels like they are creating their own universe. But for us, getting married really did set off tremors that ripped through the solid surface of our culture. After our union was announced, we received thousands of letters from around the United States, from Canada and Mexico, from Chile, Argentina, Norway, Israel, and India. The letter writers hailed our wedding as both a model for action and an inspiration for dreams.

Of course, we didn’t think of ourselves that way. We were young and in love. We were announcing who we were, pledging to love and honor each other, to uphold our commitment through sickness and health. But we did understand that we were jump-starting social change by tossing a monkey wrench into an antiquated system. Then we stood back, our arms around each other, and waited as the system struggled to reboot.

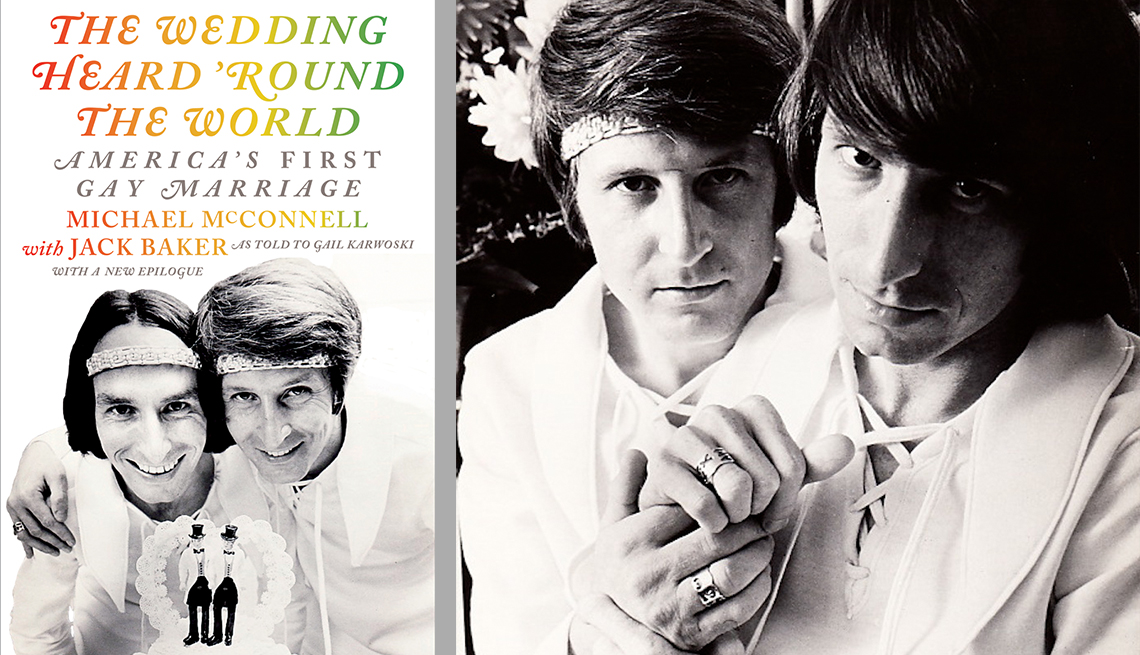

My husband is Jack Baker. He became the darling of the national media in 1970, the year he was elected the first openly gay university student body president. My name is Michael McConnell. Ours is the world’s first gay marriage.

Book cover, University of Minnesota Press. Photos by Paul Hagen

From “Married Life” Chapter

Meanwhile, we were still awaiting the U.S. Supreme Court decision on Baker v. Nelson, concerning our Hennepin County marriage license. In this case, Jack had asked Minnesota’s Supreme Court to recognize an inherent right of same-sex couples to marry. The way he posed the legal question was critical — he purposefully framed the legal question so that it involved a state’s interpretation of the federal constitution. He knew the U.S. Supreme Court was required to review any case that came before it involving this kind of question. Furthermore, this kind of case would be allowed to bypass the lower courts and be appealed directly to the U.S. Supreme Court. (Congress has since abolished this option.) Lawyers for Hennepin County insisted that there was no need for the high court to decide our claim because all issues had been resolved when Blue Earth County issued us a marriage license.

In the fall of 1972, Jack entered his last term of law school with plans for a December graduation. That October, we finally received the U.S. Supreme Court’s reply: another fizzle. The judges dismissed our case “for want of a substantial federal question.” That’s courtspeak. Jack said it meant that the court was not ready to answer the question that our case posed at that time. In other words, the court did not reject our claim; instead, it chose not to hear our case, so Minnesota’s decision would be allowed to stand. Since marriage contracts are traditionally governed by the states, the U.S. Supreme Court would step into this area only if it saw a blatant inequality in a state’s action.

But the meaning of the words “for want of a substantial federal question” was fuzzy enough to cause a debate among legal scholars that lasted for over four decades. In a column carried by The New York Times (“Wedding Bells,” in the Opinionator, March 20, 2013), Linda Greenhouse wrote that the court’s action was “a formulaic way” to say “there is so little to this case that we don’t even have to bother hearing it.” She also wrote that our case has been cited as a precedent for courts hearing gay marriage cases ever since. (Perhaps that explains why the U.S. Supreme Court felt the need to declare “Baker v. Nelson must be and is now overruled” when it finally ruled on gay marriage in 2015.)