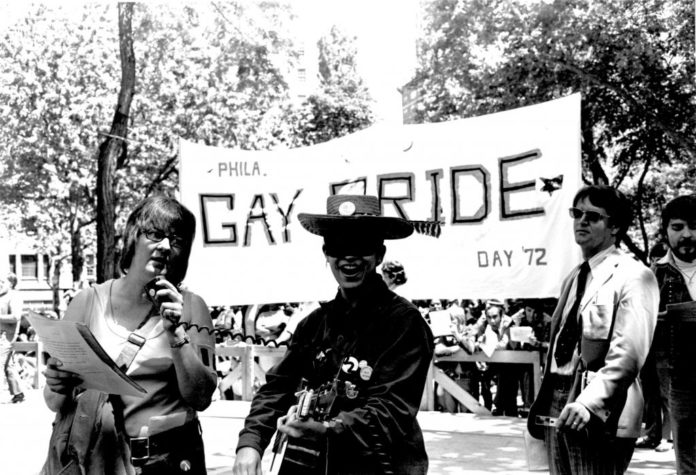

I was a 17-year-old street kid, a runaway dropout, when I volunteered at the first Philadelphia Gay Pride March. The previous summer, I had joined the Gay Activists Alliance, one of the groups involved with the demonstration on June 11, 1972. I remember lending a hand by spreading leaflets, using evaporated milk to stick event posters to poles and buildings, and acting as a marshal during the event.

I was one of few Black people and the only transgender and intersex person (I don’t call myself a trans woman) who worked on the march that year.

The event helped me make lasting connections. At the training for march marshals, I met another gay teenager named Steven Janofsky, who became a close friend until he died of AIDS 17 years later.

After the march ended, some of my fellow activists and I ate together at Day’s Deli at 18th and Spruce. I complained about gay men always wanting to have sex immediately. A tall lesbian with medium brown skin and a large afro gave me parental advice, and told me I didn’t have to have sex any sooner than I wanted to.

This year is the 50th anniversary of that first Gay Pride March. A new group called the PHL Pride Collective organized an event that was supposed to commemorate our work — but I didn’t feel like it honored our legacy.

The 1970s were very dangerous for everybody. There were no services for gay teenagers at all. Instead, a gay teenager would receive disciplinary action in school. I was bullied for years in public school. Predatory men were everywhere. When I was younger, I mistook being molested for being gay. I was raped twice and sexually assaulted numerous times. There were no services for victims of sexual assault.

Police raided bars and entrapped gay men, drag queens and transsexuals. Victims of anti-gay and anti-trans violence had no recourse. It wasn’t even safe to get mental health counseling since electroconvulsive therapy was still being used to cure homosexuality. Most people regarded homosexuality as an unimportant issue, and even some among the counter-culture called it the result of bourgeois decadence.

That was the backdrop for my volunteering on the Gay Pride March. Back then, there were no grants or corporate donations for this kind of activism. We didn’t have the city’s support.

Gay movement work would not improve anyone’s job prospects. No one put their activism on their resumes. If someone said they were going to make a living from gay activism, others would wonder what type of acid they were taking.

Our experience was not represented at this year’s Philly Pride, especially since the new organizers billed the event as a commemoration of the 1972 march.

I contacted a member of the PHL Pride Collective to try to tell them I was a Black, transgender/intersex perrson who worked on the first March. After 10 days, I got a response from someone who said they’d share it at the next meeting, but nothing came of it. I asked some of my fellow veterans from the original Philadelphia Gay Pride Committee, and they said the new collective hadn’t contacted them either.

“It’s strange that people would organize a 50th anniversary march in honor of the first Pride in Philadelphia and not contact any of those who were involved in organizing that first march,” said 1972 organizer Tommi Avicolli Mecca, who is gay and nonbinary. “This was a golden opportunity to hear history from those who made it, and to focus a spotlight on those who are gone, but should not be forgotten.”

Consequently, they got some details of our work wrong. They tossed around the word “historic.” But misinformation was promoted as history. False history was presented as fact.

For example, the collective’s website tried to connect the Annual Reminder demonstrations to the first March, and called the demonstrations a protest against “discrimination toward the LGBTQ+ community.” That is bad history. The entire LGBTQ+ community wasn’t actually welcome at those marches — only lesbians and gay men. Lesbians had to wear dresses and gay men had to wear suits. Drag queens, butch women, gender variant people, and transgender people, were not welcome. Barbara Gittings, who led the Reminders Day Demonstrations, is being remade into the mother of the LGBT movement, when she wasn’t. Organizer Tommi recalls Gittings being upset that so many Black drag queens appeared at the front of the 1972 Gay Pride March.

That’s not the only misinformation out there about the march half a century ago. Even the Philadelphia Gay News has gotten some early details wrong. Publisher Mark Segal wrote recently that The Gay Raiders, a group he founded, participated in the first the Philadelphia Gay Pride March. But they were not actually at the march in 1972, according to several of us who were there.

My early LGBT activism probably saved my life. It also helped me develop organizational skills. I co-founded with Tommi a new group called the Radical Queens, and we published a magazine. That helped me develop a writing career while I was still a high school dropout.

The PHL Pride Collective promoted their new march as honoring people like me — per their website, one stop “features speakers uplifting people of color and trans folks” while another “a tribute to LGBTQ+ elders and youth.” I am a Black transgender and intersex senior, and they did not reach out to me, or anyone else from 1972. I may be the only Black person alive who worked on the March.

My fellow activists and I do not understand why the anniversary was celebrated, but the people who worked on the original march have been ignored and excluded.

“Now there has been a grand celebration of the 50th anniversary of the 1972 march, but I see little effort to reach out to the veterans of this historic event, neither organizers nor participants,” said Laurie Barron, a retired social worker who sang at the rally preceding the march. “And it wouldn’t have been all that difficult, as the William Way Community Center and Archives has contact information for many of us. Young LGBTQ folks use phrases like ‘We stand on the shoulders of pioneers,’ but when they have an opportunity to meet us, we’re invisible.”