He was a man. It was not a declaration of modesty, but a demand of basic respect. He was a man. This is what Bill Russell sought as his epitaph and he profoundly earned it, writes JASON GAY.

He was a man. This is what Bill Russell sought as his epitaph; He said it himself in the closing sentence of his crushingly pointed 1966 autobiography, “Go Up for Glory.” That book remains one the greatest sports books ever written — brutally candid about his profession, teammates, coaches, and the Black experience in America, and published when he was still an active basketball star, if you want to know how worried Bill Russell was about telling the truth.

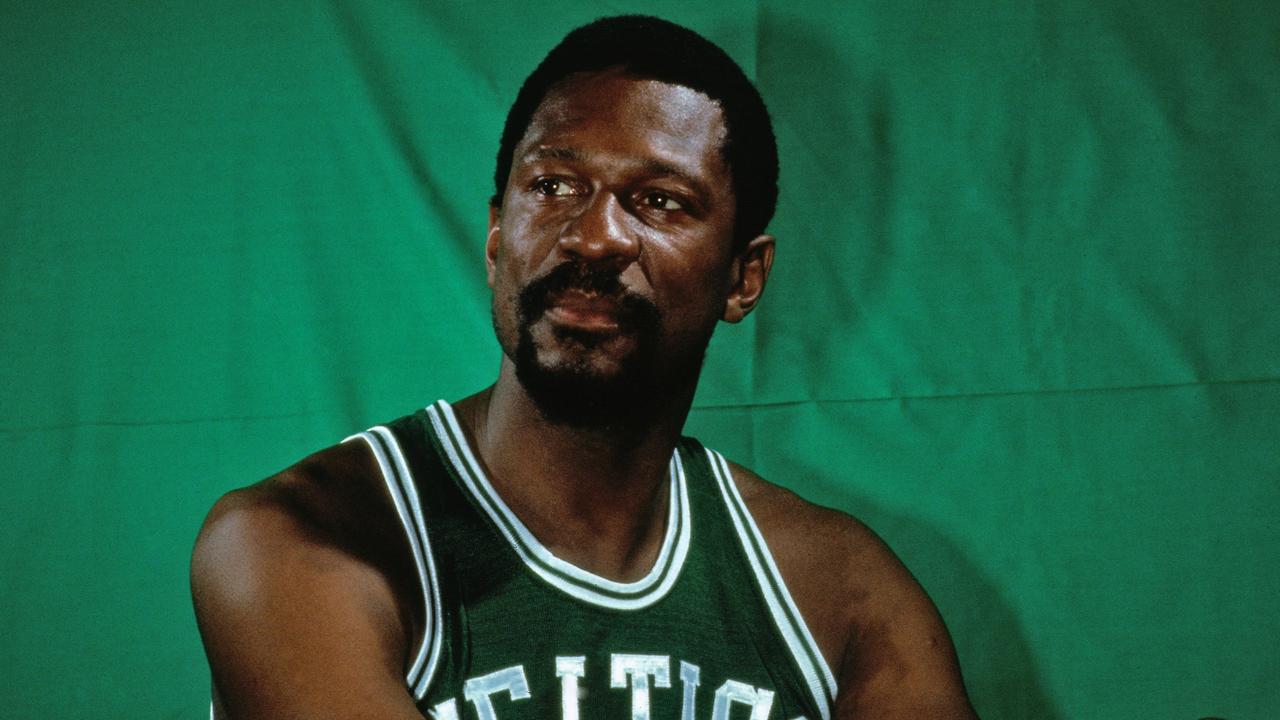

He was a man. It was not a declaration of modesty, but a demand of basic respect. Russell, who died Sunday at age 88, is inarguably one of the greatest athletes in the history of team sports, collecting 11 titles in 13 seasons with the Boston Celtics. But Russell’s essential legacy is his lifelong insistence on being rendered as a complete human being, with all rights, privileges, fears and frailties — “a man, nothing more,” as he put it more than five decades ago.

He was ruthlessly honest. He came of age in Louisiana, then Oakland, at a time when blunt racism, segregation and vestiges of slavery were norms, and moved from college (where the sport tried to curb his dominance by widening the foul lane) to the NBA in an era when a rival club owner could discuss quotas and whether or not Black players should be allowed to guard white stars. Some stories are well known — Russell and teammates boycotting a game in Kentucky after being refused service at a restaurant; Russell returning to his home in the Boston suburbs to find it trashed, a racial epithet scrawled in excrement on his wall. There were other humiliations — the way white coaches asked Russell to pal around with Black players, assuming they would be fast friends; A restaurant guest flipping Russell her keys, thinking he was the parking lot valet; A Boston neighbourhood petitioning to try to stop Russell and his family from moving there.

He moved there, nevertheless.

More importantly, he told us about it, in real time, because it mattered. The world was changing and Russell wanted to be a part of it. He found kinship in Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and also Malcolm X; He stood on the steps at the March on Washington, but also worried that the movement — he preferred calling it “human rights,” instead of civil rights — had become too wide and complacent. He bought a rubber farm in Liberia and when a reporter asked him if he intended to reject the U.S. and move to Africa, responded: “Yeah. Maybe I will. I’ll get away from you, anyway.” The reporter published only the first part of the quote, not the second.

Amid all of it, his Celtics teams won, and won, and won some more — the most stirring run of dominance in league history. Russell may have been singular as a person, but as a player, he bought fully into the brilliance of teamwork. Red Auerbach’s Celtics were fluid and unselfish, and Russell regularly sacrificed individual glory for group accomplishment. With those fistfuls of championship rings came a lifetime of friendships with players like K.C. Jones, Sam Jones, Tommy Heinsohn, John Havlicek, Frank Ramsey and Thomas “Satch” Sanders. He stayed loyal to Auerbach, who manoeuvred to land him and hired him as the NBA’s first Black coach, and Celtics owner Walter Brown, who delighted in tweaking the bigotries of his ownership brethren.

Along the way, he was labelled “difficult” and “prickly,” sometimes because he could be, but more often because he refused to varnish reality and play the role of the grateful athlete. Russell didn’t seek to make his audience comfortable, and here, it is possible to see a link to current efforts to sanitise American history and sand the edges off of inconvenient truths. There remains a spurious notion that to teach — or even raise — uncomfortable facts of racism, slavery and other sins is somehow to condition people to despise themselves or their country. We continue to mock athletes who do not express proper gratitude and step into social issues beyond their sport. Here we are, a half-century later, still regulating the lane.

Russell wouldn’t want to see the edges sanded off his complicated life, either. In death, Russell has been hailed as a “giant,” but he hated the term, because, taken literally, it recalled “a whole world of years when people made fun of you or looked askance at you because you are different.” He would grow to be 6 foot 10, made a case as the greatest teammate ever, and became one of the most courageous examples of the athlete as a public citizen. But Bill Russell wanted something more profound. He was a man.