SIOUX FALLS, S.D. (KELO) — Being LGBTQ in South Dakota in the 1970s was risky.

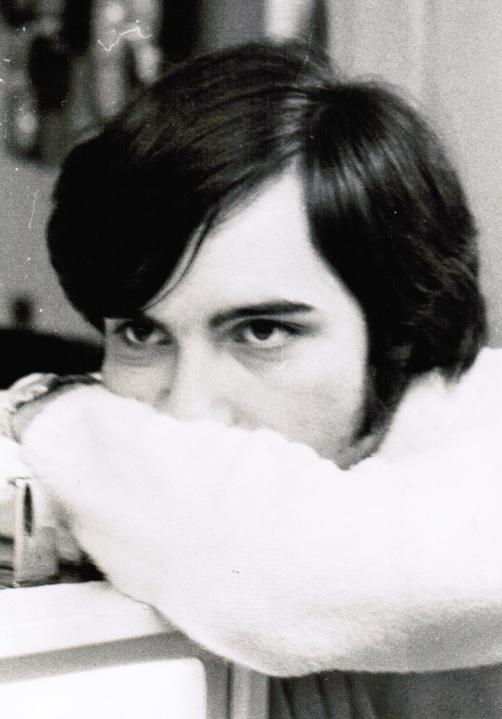

“The fear was terrible,” Linda Rohrs said. Rohrs now lives in Port Townsend, Washington, but she grew up in Rapid City.

Rohrs knew in high school she was a lesbian but feared she’d be judged and ostracized if she ever came out to anyone.

“We were afraid of losing our jobs, of losing our houses, of losing our families,” said Nancy Rosenbrahn of Rapid City.

Rosenbrahn, Rohrs, Scott Norman and Mike McGirr lived in South Dakota before gay marriage was legal.

They were living as LGBTQ residents in South Dakota before anyone had really thought of a gay pride parade in Sioux Falls or Brookings or anywhere in the state.

Rapid City became a haven for the four residents.

Back in the 1970s, Rapid City had more of a “Iive and let live” attitude, Rohrs said.

The Black Hills Gay Coalition

McGirr and Norman met at South Dakota State University. They became friends and eventually partners.

“In 1972, we moved to Rapid City. I started a new life,” McGirr said. “It was one of the most rewarding times of my life. We had a good group of friends, straight friends and gay friends. I felt liberated.”

The couple was instrumental in starting the Black Hills Gay Coalition.

“At the same time the National Gay Task Force took a shine to me and I was elected to the board for four or five years,” Norman said.

Norman also successfully requested a sexual orientation clause in contracts at the local radio station where he worked.

“I was pretty good at what I did and they didn’t want me to quit,” Norman said with a laugh. But it was also a sign that the young manager of the station didn’t think sexual orientation was a big deal, Norman said. “There was other stuff to worry about,” he said.

The policy was in place before there was any state or national sexual orientation protection for jobs. People could get fired for being gay.

The state did pass a law in 1972 that protected people from discrimination for jobs based on sex but that did not include sexual orientation and gender identity.

In 1976, the National Organization for Women (NOW) asked Rohrs to speak. “They asked me to speak about being a lesbian,” Rohrs said. NOW is an advocate organization for women.

“It was scary coming out as a lesbian to the people in Rapid City,” Rohrs said.

But she was building a support group through the local gay coalition and people like Rosenbrahn, she said.

While the LGBTQ community was making small strides in the 1970s in Rapid City, no one forgot how risky it could be.

Rosenbrahn recalled how communication still needed to be secretive in the mid-1970s. House parties were often the way the LGBTQ could meet.

One night a friend spotted a police squad car near a home. Rosenbrahn said the group immediately thought the cop was there to get them.

The discreet gatherings were “the only place where we could get together and be ourselves,” Rosenbrahn said.

“That spoke loudly to our fear,” Rosenbrahn said of the reaction to the police car.

Sodomy and other laws still existed in South Dakota then. The law changed in 1976 to legalize private, adult, consensual and non-commercial acts of sodomy.

Public displays of affection between same-sex couples were rare, if they happened at all in the city and state.

“There were a lot of alcoholics and struggles in people’s lives,” McGirr said. “People were struggling, losing jobs. People were thrown out of the house by their families and having to move away.”

Gay advocates established a 24-hour phone line to help others.

“We had children so we got (to volunteer on) the weekends,” Rosenbrahn said herself and then partner. “We got (at least ) three suicide calls.”

Rosenbrahn said they were able to help on those calls.

Meanwhile, advocates were dealing with their own issues.

Rohrs lost friends after she told them she was a lesbian. Her family hadn’t yet accepted her as a lesbian.

McGirr was distant from his own family and struggling with internal issues of fear and hate.

Rosenbrahn was working to retain custody of her children knowing that her sexuality was central issue.

Still, the advocacy work continued.

McGirr and Norman conducted educational workshops “to help people accept themselves,” McGirr said.

The coalition established a post office box to receive mail. It also published a newsletter sent to a few hundred people.

“People who were isolated in small towns, farm and ranches, who never had any connection to the gay community, just like me,” McGirr said.

Norman and McGirr had also attended the 1974 South Dakota Democratic Convention to advocate for gay rights.

A supportive legislator advised them that this was not the time for gay rights legislation because the Legislature had just removed all references to sodomy from the state’s criminal code. Norman said the legislator said the Legislature did not need to be reminded of that action.

Advocacy was gaining ground in other states.

In January of 1977, the Dade County Commission in Miami, Florida, passed a gay rights ordinance to protect gay people.

But then came Anita Bryant, a singer and self-described born-again Christian who successful campaigned against the ordinance. Voters repealed the ordinance. Bryant started the “Save Our Children” campaign and the rallying cry was “homosexuals cannot reproduce, so they must recruit.”

Schools were one of the points of emphasis for Save Our Children.

Bryant’s efforts started a wave of repeals of gay rights ordinances in several cities and helped spark a movement to discredit gay rights by Jerry Falwell and the religious right (as it was known in the early 1980s).

AIDS and the 1980s

McGirr and his new partner left Rapid City in 1979. Job changes took them to California in 1981.

“AIDS was just starting then,” McGirr said. “No one knew much about the disease or how it was transmitted exactly and how it was transmitted. The medical community was afraid of it.”

“People didn’t understand it,” McGirr said of AIDS in the early 1980s.

Norman said the national government’s response to AIDS was “scary.” Sen. Jesse Helms suggested at one point that all gay men should be quarantined, Norman said.

While Norman and his partner were living in Seattle where AIDS test were available and so was care, he said they kept their car full of gas and their passports handy.

Rosenbahn said advocates were helping those with AIDS in South Dakota travel to health care in Denver because there weren’t any South Dakota hospitals that would take them.

“Gay women stepped up to help,” Rosenbrahn said.

A segment of Christians used AIDS as example of how homosexuality was a sin.

Rohrs recalls seeing signs that said, “God hates fags.” She had some conversations with people who held that religious view.

“I said if, ‘God hates fags, God must love lesbians. We must be God’s favorite because lesbians are the least impacted by AIDS,’” Rohrs said.

By the end of 1984, AIDS had killed more than 3,500 in the U.S. About 7,500 were infected. The disease swept through the gay men’s community but drug users also contracted the disease through shared needles. It can also be transmitted by straight couples through sex. In some cases, it was passed in pregnancy from mother to child.

Then President Ronald Reagan “wouldn’t do anything about it,” Rohrs said.

Reagan first publicly mentioned AIDS in 1985 and it was an epidemic by then.

It was devastating to watch normally healthy men die, Rosenbahn said.

McGirr said although he and his partner “somehow managed to avoid AIDS ourselves, there was no avoiding it in the community. It was a horrible experience.”

A good friend whose family had immigrated from Mexico contracted AIDS.

“He had been in the Navy. Thank God he was eligible for veteran’s benefits,” McGirr said.

The friend ended up in a veteran’s hospital. “They didn’t know what to do with him. They had him in isolation,” McGirr said.

The friend had never told his family he was gay. His family came to see him in the hospital.

“It was pretty traumatic,” McGirr said, pausing as he remembered his friend.

By 1987, 47,000 people had died of AIDS in the U.S. Reagan had put money into AIDS research in 1985. In 1987, a public AIDS awareness campaign was launched.

Rohrs said something shifted in the response. “At first these men were shunned and shamed,” Rohrs said.

But as Americans began learning more, there was more caring and more options for medical care for AIDS patients.

“AIDS took the veil off,” Rosenbrahn said. People began to learn that their family members and friends may be gay, she said.

But the LGBTQ community also got mad, she said.

Activist Larry Kramer started the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (Act UP). He had first helped start the first gay men’s health center for HIV positive patients in 1981.

Act UP is credited with an aggressive approach to demand more AIDS research and to end discrimination against gays and lesbians.

Life today in and out of South Dakota

Of the four, only Rosenbrahn remains in South Dakota. Her wife, Jennie, died in March.

Rosenbrahn and Jennie were among the six couples who sued the state for its ban on gay marriage. The case didn’t continue after the state lost a motion in court to deny their marriage in South Dakota as the Supreme Court upheld gay marriage with a 2015 decision in the Obergefell vs. Hodges case.

Norman moved to Seattle where Doug, his partner of nearly 40 years recently died. He’s letting those younger then him advocate for the LGBTQ community.

Rohrs lives in Washington state. And McGirr lives in California.

They are aware that in 2022 rights for the LGBTQ have advanced beyond their time in South Dakota.

Although what may seem a simple thing, same-sex couples holding hands in public, is a big deal, Rohrs said.

But the LGBTQ community is still facing challenges.

Rosenbrahn said pride parades such as the one recently held in Sioux Falls are celebrations of people but they are also “peaceful riots.” Events and parades must also be times to remind the public that the LGBTQ community deserves its civil rights, she said.

Seattle is a gay-friendly community. But “I still hear horrible stories of families that throw (gay) kids out of the house,” Norman said.

While he may not be advocating, he’s giving money to causes that help those kids.

It’s good that the gay community is so integrated into Seattle but he knows there are a lot of young kids who end up in the city from other states. “Some of them are homeless,” he said.

And some of those kids are from South Dakota, Norman said.

Norm describe some legislative proposals and actions taken in South Dakota over the past several years as “bizarre.”

A law that bans transgender girls from participating in girls sports in the state recently took effect.

In 2016, Gov. Dennis Daugaard vetoed a law that would have required transgender students to use bathrooms and locker rooms that match their birth sex. A 2019 proposed bill that would have barred public schools up to grade K-7 (12-13 years old) from instructing students on gender identity and expression did not pass.

In 2020, a legislator introduced a bill that would not “permit any form of marriage that does not involve a man and a woman” or allow counties to issue marriage licenses to same-sex couples. It would also legalize conversion therapy, prohibit the state from recognizing LGBTQ+ people as a protected class from discrimination, as well as ban “drag queen storytime at libraries or schools.”

The bill did not advance.