Queerness has always been a part of motion pictures, only the ways in which it has historically been portrayed has varied from decade-to-decade over the past 130 years. Those with insight to the pre-1927 silent film era will know that queer characters, be that homosexuals or “cross-dressers” served as subjects of amusement in American cinema, while being given actual dramatic stories across the pond in Europe. For a few years in the late 1920s and early 1930s, gay male characters were a constant presence on screen in the form of the “Sissy” archetype, that is: effeminate, non-sexual, and non-threatening. Soon, even this meager representation would go the way of the Silents. Once the Hays Code, a series of rules set to establish “upstanding moral values” in American cinema, banned any instance of overtly homosexual characters, queers on screen were offered one alternative: a life of crime.

The Hays code could not ban the actions of queer people behind the scenes, and many writers, directors, and even actors, would devise ways to present a queer sensibility on film, whether through aesthetics or characters. Unfortunately, those characters were forced into the dark corners of society, threatening our clean-cut heroes and the heteronormative way of life, as the only way they were allowed to exist on screen is if they were portrayed as outright villains, destined for retribution by the film’s end. Queer-coded characters of this sort were often portrayed as social cast-outs, overly concerned with their appearance, and tricky in their actions and dialogue. Male queer characters often had an air of snobbery, and would sometimes obsess over a female character as if to covet their unattainable femininity (Waldo Lydecker, Laura; Joel Cairo, The Maltese Falcon; Addison DeWitt, All About Eve). Lesbian coded characters would similarly desire to “obtain” a female protagonist in an almost psychosexual manner, and would dress and present themselves completely outside the norm of female sexuality (Mrs. Danvers, Rebecca; Eve Harrington, All About Eve; Miss Holloway, The Uninvited).

Once the Hays Code lost most of its power by the early 1960s, film directors were able to make direct allusions to homosexuality, though still in reflection of audience’s ignorance and fear. While some underground queer filmmakers explored the complexities of gay living in the latter half of the 20th century, the mainstream still presented gay, lesbian, or transgender characters either continued being social deviants, or were subject to immense tragedy (The Crying Game, Cruising, The Boys in the Band, Dressed to Kill, Midnight Cowboy).

By the late 1980s, when the AIDS crisis was gripping America and setting hostility towards gay people at an all-time high, queer filmmakers decided to take their own stories into their own hands. Film critics B. Ruby Rich first coined the term “New Queer Cinema” in Sight & Sound in 1992, referring to a newfound trend of independent gay cinema sweeping American film festivals. Many of these films existed in conversation with the past century of queer portrayals on film, turning the last century of gay-villainy on its head by directly linking their character’s sexuality to their criminal behaviour as a sort of meta-commentary on Hollywood’s complicated relationship with its gay characters and audiences. In her article, Rich refers to two films, Swoon and The Living End, which represent a central tenet of New Queer Cinema: be gay, do crime.

Both Swoon and The Living End have obvious historic cinematic influence. In 1924, the murder trial of Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb gripped the nation for its depravity and intrigue. While the basis in 1948 for Alfred Hitchcock’s Rope (based on the 1929 play of the same name), the true story of the grisly murder of a young boy in Chicago is far more gruesome (though I’ll spare you the details). Filmed in black and white, director Tom Kalin blends the aesthetics of the 1920s with an atemporal feeling of modernity. In addition to the obsession of planning “the perfect murder” Halin focuses on the boys’ obsession with one another, which took the form of a bizarre master/servant relationship that allowed the two men to egg each other on into this horrific crime. The real life, highly publicized trial exposed much of America to a type of psychological criminality, and sexuality, that they had never before witnessed. This would only contribute to the false, widely-held notion that queer people are inherently villainous, containing overt parallels to the AIDS crisis during which the film was made, when queer persons, especially gay men, were made villains by their mere existence.

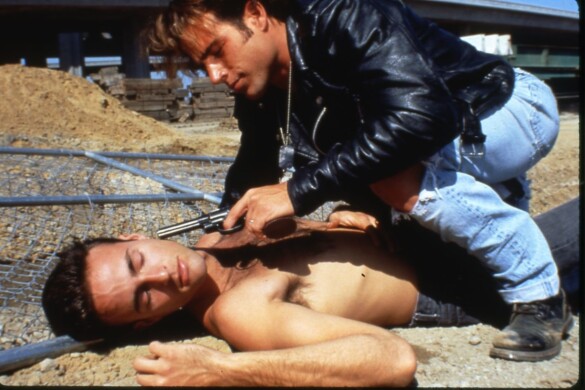

Departing from the world of the aesthete, the educated, the refined, we have Gregg Araki’s gay criminal road trip movie: The Living End, starring Mike Dytri and Craig Gilmore as two very different men, one law-abiding and one a rebel, each with a recent HIV diagnosis, and both with their own societal frustrations. The third feature film from Araki, it contains heavy influence from 1960s exploitation films with the directors signature nihilistic touch. Like Swoon, it recognizes the type casting of queer persons as villains, and turns it up to eleven. Frustrated by their lot in life, the two men decide if society is going to see them as a pair of villains, then they might as well become one. The film, and the characters, disregard the natural order of things, leading to eighty minutes of chaos, anger, and raising hell.

Four years after Rich’s original article, the Wachowski sisters became a part of the NQC trend (although with decidedly more mainstream distribution) with the neo-noir Bound, starring Jennifer Tilly as Violet, a mob moll and Gina Gershon as Corky, a tough ex-convict, who team up to scam Violet’s boyfriend out of a couple million dollars. Taking a hint from film noirs of the 1940s and 1950s, the film is shadowy, sexy, messy, and intentionally confusing. Violet and Corky see one another as an escape from their less than stellar situations. In this case, like Thelma & Louise flying off of a cliff to escape the grips of the patriarchy, Violet and Corky’s queerness is their liberation.

These three films, as well as a great deal of other queer cinema titles, demonstrate through self-awareness and unconventional cinematic techniques the paradoxical queer desire to acclimate to normative society while being systematically eliminated by it. Given that during Hollywood’s heyday, being gay was a crime in itself, the conscious portrayal of queer criminality by queer directors the opportunity to reconstruct a narrative of oppression and invited audiences to reconsider a century of nostalgia.