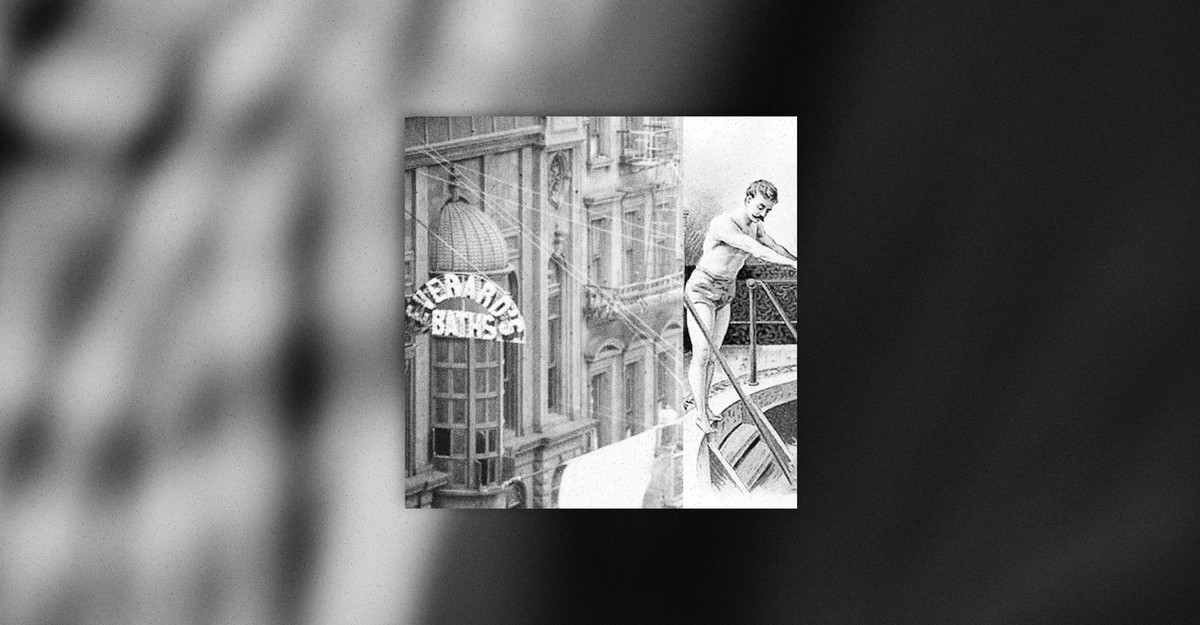

An aspiring dramatist named Emlyn Williams watched the rain fall from his bed in his New York City apartment. He had just turned 22 and had performed in a play the night before, but—as he recalled years later in his autobiography—“the feeling of being alone darkened into loneliness.” Then a thought darted across his mind. Unlike in London, where he had spent time after graduating from Oxford, there was a place for him to go in New York City: the Everard Baths.

So he swung his feet off the bed, put on his raincoat, and “hurtled down into the drizzle over to Madison Square and up Broadway” to 28th Street, which, in 1927, was in a neighborhood of brothels, theaters, and the infamous Haymarket—the so-called Moulin Rouge of New York. Tucked in the middle of the street, the Everard Baths was a church that had been converted into a Turkish bathhouse by an Irish financier in 1888.

When Williams entered the bathhouse, it had become a clandestine establishment for men who wanted to have sex with men. As Williams later recalled in his autobiography, he paid a dollar to “an ashen bored man in shirtsleeves,” who gave him a towel and a key on a bracelet to a cubicle that had a “workhouse bed.” Williams walked toward a “large floor as big as a warehouse” with “rows of private windowless rooms” that appeared as dark cells. When he got to his room, he undressed, put on a threadbare cotton robe, and wandered through the bathhouse. He passed by other men who behaved as if they were alone, their “eyes anywhere but on another walker.” He described them as ghosts and even referred to one man as “a solicitous suburban Dracula.” When he returned to his room, he laid on the bed and tried to make sense of the sounds that he heard: a door slammed shut, the thud of a shoe on the bare floor, the snap of a cigarette lighter, whispers that sounded like the chatter of men talking in a gym.

This description was hardly a ringing endorsement, but the possibility of sex in a dingy bathhouse in a salacious part of the city was how Williams and many other queer men found each other in 1927. Though subject to police raids, these establishments were, before the 1969 Stonewall revolt that signaled the rise of queer liberation, some of the only places gay men might find community. And the uninhibited embrace of sex that they represented, even if far from universally shared among gay men, was something many fought to defend.

This attitude helps explain public-health agencies’ peculiar reluctance to speak frankly about the risks of monkeypox, which, in the United States, has been spreading rapidly—and almost exclusively among men who have sex with men. The CDC has recently—and belatedly— recommended that people avoid going to sex clubs and other spaces where “intimate, often anonymous sexual contact with multiple partners occurs,” given that the virus is more likely to spread in these environments. But this message competes with well-meaning assertions by other experts that anyone can get monkeypox and that the virus can spread via, say, shared linens.

Many gay men have criticized the CDC’s recommendation because they fear a slippery slope. They point to the history of HIV/AIDS and how government authorities pathologized gay culture—and gay people—as aberrant and shut down bathhouses, including the Everard Baths, which Mayor Ed Koch ordered closed in 1986. As a gay man and a historian of infectious disease, I know about the harm that comes when public policy becomes infused with homophobia. Yet protecting gay men from discrimination and stigmatization today does not require public-health officials to tiptoe around how monkeypox is currently being transmitted. Drawing imprecise historical parallels between Williams’s day and ours—or between HIV and monkeypox—adds confusion to an already contentious public-health crisis, and it makes the straightforward decision to simply refrain from high-risk sex far more politically fraught than it needs to be.

Two years ago, public-health officials urged the public to stay home to stop COVID-19. But some agencies have become so wary about advising sexual abstinence of any sort that they won’t even tell men with symptomatic monkeypox infections to avoid sex for a few weeks until they recover. Officials in New York and elsewhere have suggested, as a harm-reduction measure, that sufferers cover up their lesions during sexual activity. (In many patients, those sores are excruciatingly painful and are in locations that are difficult to cover.)

When contemporary gay activists scoff at talk of limiting sexual activity, they often imply that the impetus for any such restraint has historically come from the government. Yet even before the devastation caused by HIV, criticism of anonymous sex had been building within the gay community. In 1978, Larry Kramer—who later became a leader in AIDS activism—published Faggots, a novel that called into question the sexual libertinism of the era. Loosely based on his quest to find a meaningful relationship, Kramer’s book indicted orgies, urban bathhouses, and sex-filled summers on Fire Island, which, he believed, prevented gay men from having intimate, monogamous relationships.

Others shared many of Kramer’s concerns. Craig Rodwell, a gay political leader who helped spearhead the first Pride march, worried that the emphasis on sex within the gay community would undermine efforts to sustain the movement. He founded the first-ever gay bookstore, the Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop, a venue that offered an alternative to the sex culture. Rodwell was not a prude and often cruised parks himself; by some accounts, his infidelity led to the demise of his relationship with the legendary activist Harvey Milk. But Rodwell also wanted to create nonsexual ways for gay people to interact.

Today, medical advances have made HIV transmission largely preventable, at least for those with access to those advances. And queer activists now confidently assert that the government shutdown of bathhouses did nothing to contain that virus. In fact, researchers have proved no such thing. We lack convincing evidence because few, if any, epidemiological studies rigorously investigated this question in the early 1980s. The urgency to understand the virus directed the proceeds of fundraising campaigns to virological studies. After HIV was defined as a retrovirus, funding was then allocated toward creating therapeutics to help slow down the virus’s assault on the immune system.

Had epidemiologists been able to obtain funding back then to visit gay neighborhoods and examine how the closure of bathhouses affected infection rates, they might well have learned that many gay men began boycotting bathhouses before the government shut them down and that others refused to even come out of the closet to pursue sex with men. When confronted with a deadly disease, gay men adjusted their behavior in other ways, adopting condoms and in many cases reducing their number of sexual partners.

Further comparisons between HIV and monkeypox tend to pivot on the argument that if gay men are targeted as the main population at risk, monkeypox will be seen as only a “gay disease.” That sentiment was indeed evident in the early days of the HIV epidemic. But by the early 1990s, safe-sex campaigns aggressively targeted heterosexuals as well. The message filtered into popular culture. The music video for the 1995 hit “Waterfalls” by the trio TLC portrays a woman who is exposed to HIV from sex without a condom; to encourage young women to talk about safe sex, members of the group wore wrapped condoms on their clothes.

In any case, the gay community is better positioned to counter stigma in 2022 than in the ’80s, when there were few out gay journalists and editors in positions of power in the mainstream media to provide unbiased accounts of the HIV crisis. Homophobia had quarantined many LGBTQ journalists to the queer press, which government and medical authorities overlooked despite its indispensable reporting. That is far less likely to happen today. After publishing an article in The Atlantic in May on why gay men needed a specific warning about monkeypox, I have been inundated by interview requests from reporters, both gay and straight, at some of the nation’s leading media outlets, who are desperately trying to make sense of the epidemic and the discourse surrounding it.

If there is one lesson Americans can learn from HIV, it is about the harm that resulted from the framing of the public-health crisis as predominantly affecting white men. This eventually contributed to high rates of infection among Black men, who lacked equal access to information about prevention, testing, and treatment. This history should remind us that gay men are not a monolith; that race, class, and even region affect who has access to information; and that the lack of forthright information about how a virus spreads can lead to devastating health consequences.

For me, the most relevant information about monkeypox comes not from the history of the 1920s or the ’80s but from the social-media testimony of patients who are now suffering excruciating symptoms, in particular the seeming inability of medical professionals to provide immediate and effective care, and the fact that mysterious symptoms persist even when clinicians claim that the virus has run its course.

Every public-health crisis creates the possibility of slippery slopes—of misusing government authority in ways that end up enforcing society’s prejudices rather than protecting vulnerable people’s health. Acknowledging the role that sexual freedom has played in the gay community since before Williams’s day does not preclude taking a temporary break from multiple, anonymous partners during a crisis in 2022. I am not calling for the government to shut down gay establishments, not even bathhouses. I would prefer that gay men made the decision to be careful of their own volition. But I would also hope that public officials would base their recommendations to gay men on current information about the monkeypox outbreak.