It is early August 2022, and I am in San Francisco for a few days. In urban areas with large gay populations, monkeypox is on the mind of all my gay friends and a topic of great interest among my straight ones. Only weeks ago, monkeypox seemed like a minor issue. Now, with over 17,000 cases across the country and 3,642 cases in California alone, there are more and more stories of people who have contracted it — experiences of the worst pain ever, like broken glass scraping on skin and of the horror when the lesions travel to the genitals and anal canal, where the pain is constant and agonizing.

For those of us who are sexually active gay men, the timing seems particularly cruel. It was only recently that the shadow of COVID lifted a bit, giving something of a return to normalcy in regards to sexual practices. Monkeypox spreads through close contact, particularly sexual contact, and many gay men have contracted it. Sex and physical intimacy are dangerous again. It’s time to once again limit sexual contact — to heave another sigh and find a way to get the vaccine.

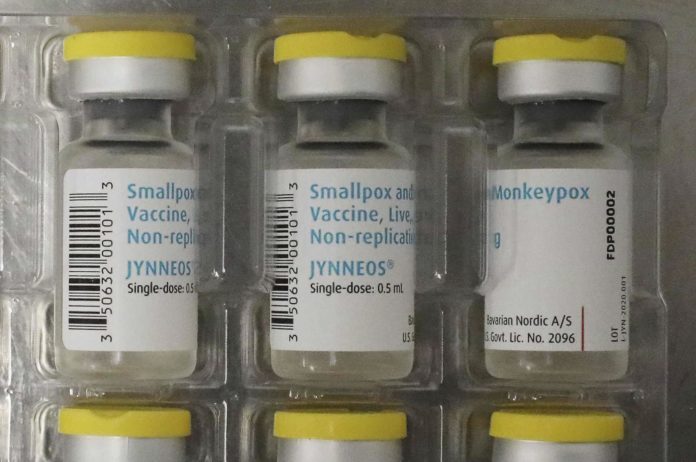

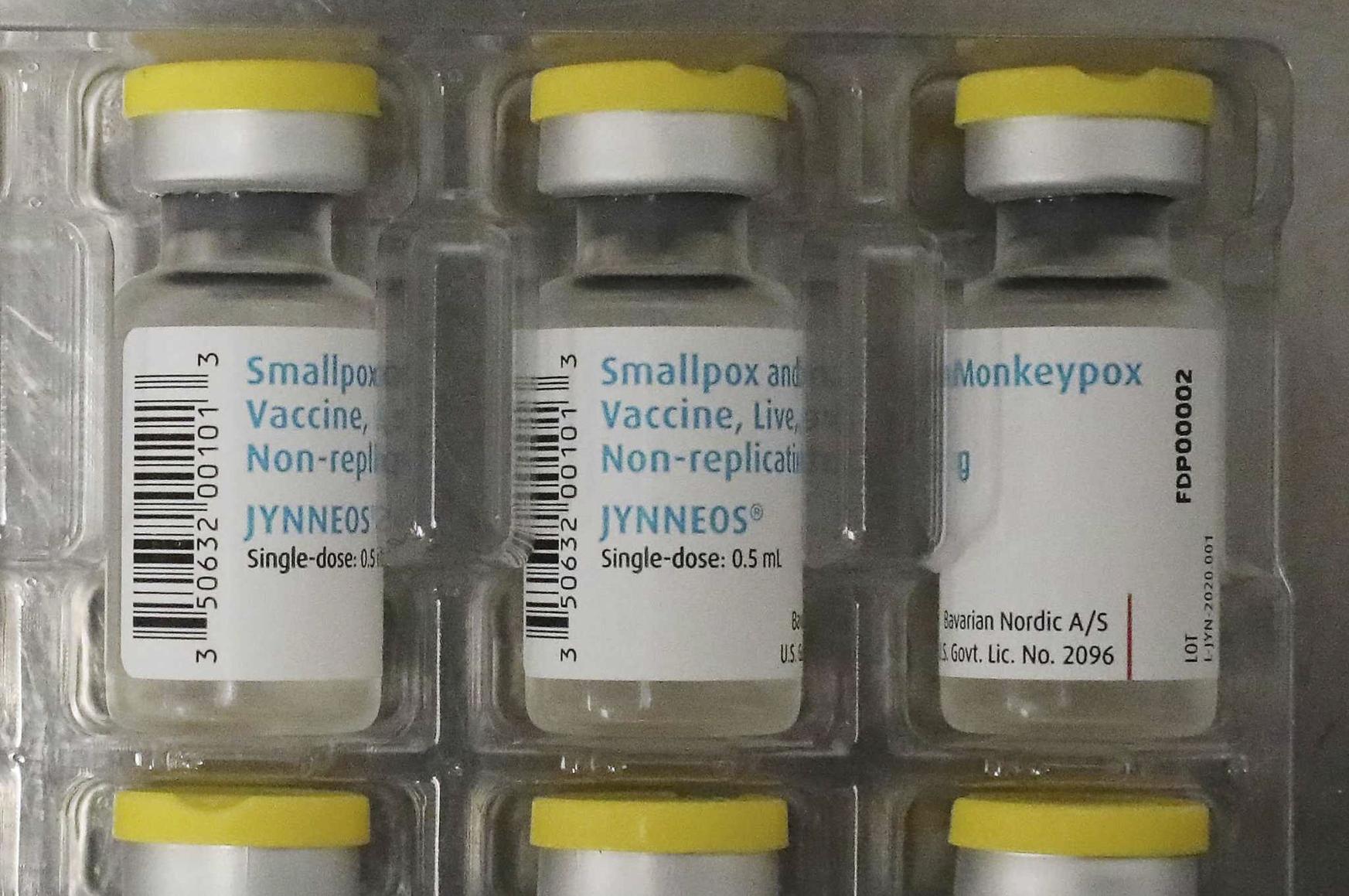

It isn’t easy. I had registered for the vaccine back home in Los Angeles and in nearby Long Beach but had been unable to obtain it. Now, in San Francisco, after 8 on a Tuesday morning, a friend texts me that he’d gotten out of bed at 4:30 a.m. to get in line at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital. Rumor was, that the hospital had a batch of monkeypox vaccine — maybe 600 doses, no one knows for sure — which were going to be given out starting at 8 a.m.

When my friend arrived at 5:30 a.m. there was already a two-block line, and he was lucky No. 125 — assured he would get the vaccine that day. His text urges me to go to S.F. General ASAP. I pull on some clothes, call a Lyft and rush out the door. I have a work Zoom scheduled later, but this may be my only chance.

When I get there, the line is down to one-block long, and there is a moment of joy and relief when a smiling health outreach worker hands me a paper slip: No. 531. I will get my first monkeypox vaccine dose that day! She also gives me a questionnaire to fill out, and a bright yellow pencil, as if I were about to commence a round of miniature golf.

The vaccine line snakes along slowly but constantly. It is a warm day in the city, and it’s nice to be in the sun. I look at my companions in line. We are gay men, most alone, some in pairs. I have flashbacks to the early days of the AIDS crisis. The desperate waiting for initial treatments, taking an early HIV test and waiting an unnerving two weeks for the result, struggling to get the first doses of combination therapies. We were stigmatized in those early days, and we fear we could be stigmatized anew.

Of course, there are more recent flashbacks, to COVID-19 — the confusion and anxiety, and also the sense of liberation and safety that came with the first vaccine dose.

About halfway through the line, an earnest young activist hands each of us a card urging us to sign a petition demanding the government take more urgent steps to fight monkeypox, including making more vaccine doses available immediately. Later, near the vaccine site entrance, I come across a huge pile of petition cards discarded on a bench. Political apathy will always exist to some degree, but I wonder how much this castoff mound may speak to the number of gay men who feel exhausted and overwhelmed in the face of a seemingly endless barrage of political and health threats.

Getting the vaccine goes smoothly. I walk to a numbered table where an intern in scrubs greets me warmly and transcribes the information on my penciled questionnaire into a database. I go upstairs to receive my vaccine. An older, jovial male nurse smiles broadly, offers me a seat, and asks: Which arm? The injection is painless, and I do not at first realize it is over. I see the nurse toss my used syringe into a gigantic red sharps box, on top of hundreds of other spent doses.

I think of all the death and suffering among gay men that the organized, friendly health professionals at San Francisco General Hospital must have seen since the first days of the AIDS epidemic. In some ways this is just another response to a health crisis, offered generously and efficiently, without judgment, and mustering the greatest resources they can provide.

Last week, California legislators and Gov. Gavin Newsom announced a plan to spend more than $41 million on the state’s efforts to fight the virus. It is welcomed news, especially in the face of a sluggish federal response to the crisis.

I walk out of the vaccine facility with a lightness in my step, knowing that I am lucky. There are still vaccines available today, just as there had been when my friend texted me a few hours earlier. I text other friends to tell them to come down here and see other men doing the same.

We are in this together — men who are still in many ways outsiders to mainstream American sexual culture, who have achieved a certain level of liberation in our celebration of the joy and intimacy of sex, and who, if we are lucky, have good friends who reach out in a time of crisis and tell us to get our ass down here right away.

Robert Whirry is a freelance grant proposal and report writer who has worked in HIV and public health since 1985.