I’m pretty sure time has stopped. Or maybe it’s simply that my heart has been forced to cease its beating. I feel as though I’m watching myself from afar, observing my eyes widen as they read the word before me over and over and over. Six letters strung together to form one of the most destructive words in the English language. One of the most painful words in any language.

“N—–.”

I sit at our kitchen table, a freshman in high school. A gay, African American male, about to go to a high school dance, reading the word sent over instant messenger by two of my classmates. Part of my heart breaks. The word used specifically to remind Black people of their supposed place in society. I’m not that word but now I am viewed as that word. I’ll never have the luxury of forgetting this first that I never wanted; this first that I did not deserve.

Alone at the table, I ignore the crack that word causes within. Instead, I give in to the fury that is bubbling up within. Something inside me twists permanently.

As I reflect on this moment in 2021, a year after the heart-shattering murder of George Floyd sparked national and international outcry, I’m inevitably reminded of how much it took to activate parts of our society into caring about Black people and the atrocious treatment we have faced for so long.

I’m also reminded of my relationship with anger as a Black, gay male living in America; a country where righteous anger as a minoritized person can lead to your death; a country where simply being born Black, simply existing with the “wrong” skin color can mean you don’t make it to adulthood.

Sadly, that online message wasn’t the last time I was called the n-word in high school. Far from it. It happened so many times I was forever on-guard. It was the same with homophobic slurs. And though I had friends, I kept the verbal assaults to myself because of the shame. I believed I was the problem.

As a young teenager, anger consumed me. There were times I felt as though I was a receptacle overflowing with the malice others had, without my consent, shoved into me. I had experienced depression and suicidal thoughts that began in seventh grade due to bullying and lack of acceptance, and so, to survive high school, I transformed myself.

I did what I could to control the pitch of my voice and I limited my expressive hand motions. I learned quickly to be friends with the “right” people, and how that somehow protected me. Blending in naturally was a luxury I didn’t have, but I tried my hardest. When I came out officially junior year it did help because people couldn’t gossip as much, asking, “Is he or isn’t he?” or “Of course he is, just look at him!” But the self-loathing remained.

Then I ran.

At age 18, I left Seattle and flew across the country to college in the hopes that it would be a fresh start; a place where I could not only study science, but openly express who I truly was. I hoped it would be a place where I could let go of anger.

Within the first weeks I was rejected from a fraternity because I was gay. Some fraternity brothers later told me how my being openly gay had led to me being “blacklisted” by two people in the fraternity at the end of voting for bids. Staff got involved. I had to relive what had happened and was told they would handle it.

Eventually, it was relayed back to me by staff that the fraternity claimed I hadn’t gotten a bid because I “didn’t get along with other people.” I was told the best that could be done was to have the fraternity brothers do “sensitivity training.”

I went on to have panic attacks—though I wouldn’t know what crying during exams or feeling unable to breathe was actually called until medical school—and failed all my first exams. I was sure I was going to fail college. At times, I sat in the shower contemplating suicide.

I furiously vowed to become friends with every person on campus. I would show those who said I “didn’t get along with people” that they had messed with the wrong Black, gay person. I succeeded in making friends, but that didn’t stop the panic attacks, the suicidal thoughts or the nightmares where I woke screaming and crying. But, harnessing my fury helped me survive.

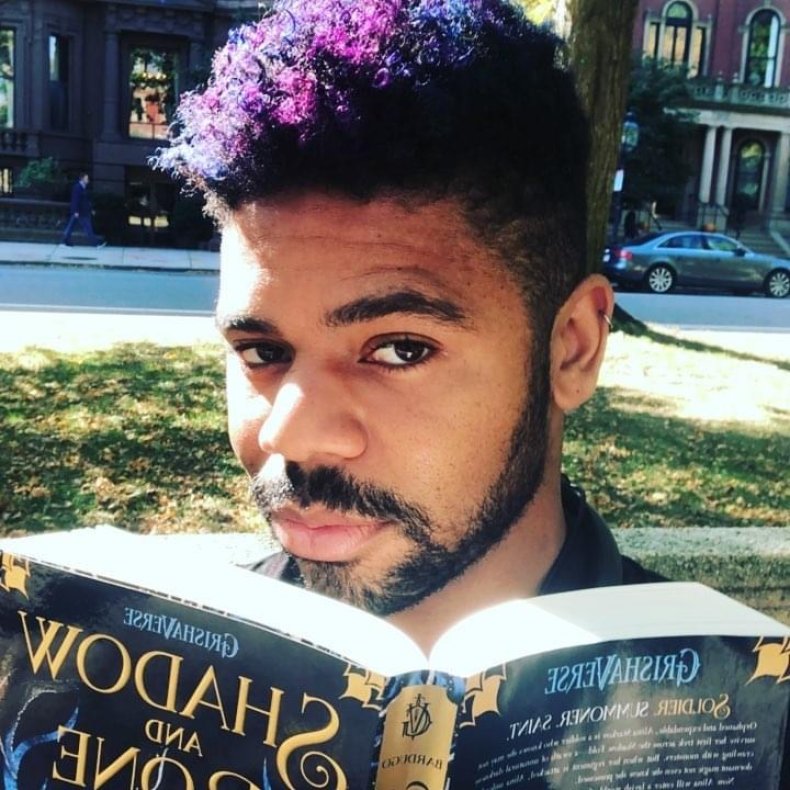

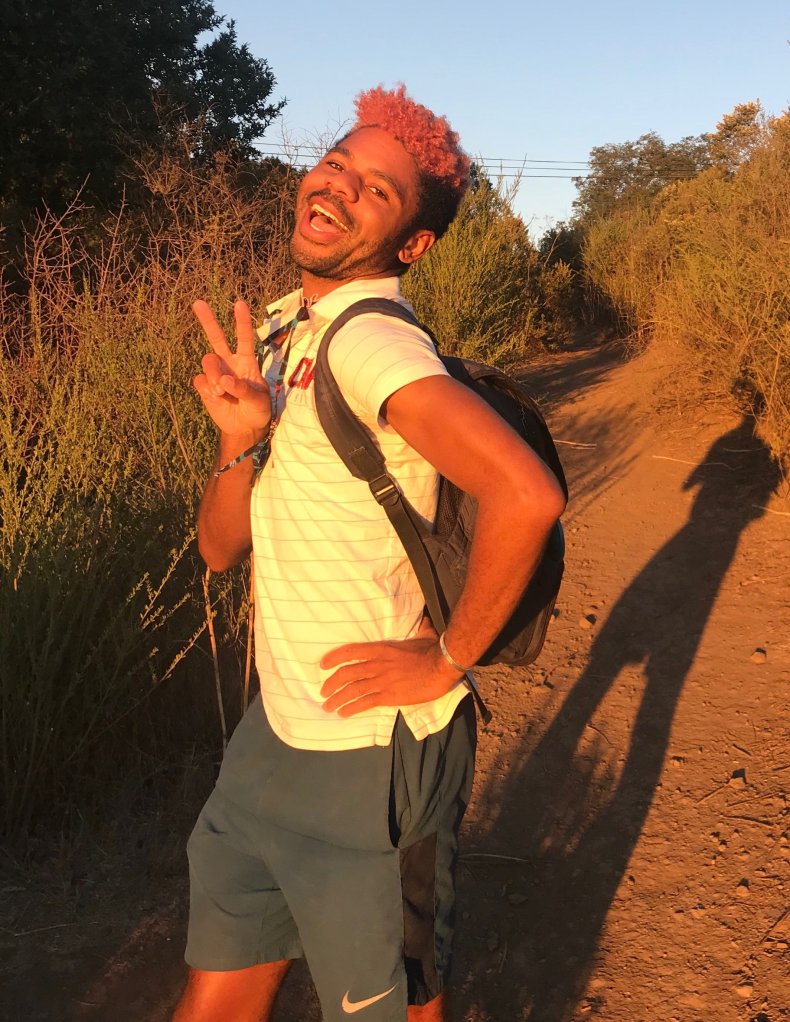

Dr. Chase Anderson

Dr. Chase Anderson

And those friends in college saved my life. Each one shared their own stories and anger. Whether it was the treatment of women in science, racism, homophobia, xenophobia, societal inequities; we sat in the chaos of the world together. They validated my feelings as I validated theirs. Just as importantly, they encouraged me to be a better person. That happened in the little moments when we stayed up with each other until dawn talking, when sharing our stories united our hearts. It was the bigger moments when friends publicly called out others for homophobic slurs, or when I then realized I could speak up against such words too. It was two friends taking the time to sit me down one day during the summer after freshman year and saying, “You can do better. We see such power in you, and you can help others. We know you’re hurting, your anger is valid, but you can also be so much more.”

These people told me they loved me for me.

By the time I entered graduate school to study biological engineering in 2013, my anger had abated and my depression had dissipated. Now when I heard the n-word or a homophobic slur, I often rolled my eyes before taking the person to task. I set boundaries with more ease. During those two years of graduate school, I felt I was living in America as my true self: a Black, gay man who was also seen as so much more. I was known for being gay and that was seen as a beautiful aspect of my overall self. I dated—a lot. I wore crimson pants to classes and lab and I was no longer afraid to be truest myself. I mentored younger classmates and worked to improve the lives of minoritized friends on campus. I had the life I had always wanted.

And yet, less than six months later, after matriculating into medical school in the fall of 2013, I was drowning. I became class president and immediately heard some of the most disgusting and disparaging comments about myself and other minoritized students I’d ever heard in my entire life. I heard them from classmates and faculty. It felt like high school all over again and it seemed that who I was—a Black, gay man—could not exist within the medical system.

Why were my classmates allowed to use discriminatory words, but the second I calmly spoke up for myself or others, it caused “friction”? Why were my words to administrators about these issues ignored by many, while white colleagues who actually made the comments were continuously praised? Why was I unprofessional for advocating for people as class president, but white colleagues being racist was fine? Near the end of my third year of medical school, I realized I could no longer excuse the imbalance. As a Black, gay man in America, it was not my job to forever subdue my anger. I chose to use it and it empowered me.

Once, a white classmate who had used the n-word during our first months of medical school said that dealing with me was like dealing with a patient exhibiting mania. I spoke with them privately and made it clear that kind of joking was not acceptable. But having to constantly set limits hollowed me out. By the time I left medical school, I felt like a shell of the person who had been flourishing at graduate school.

I longed to return to that sense of strength and confidence, but residency had other plans. First it was being called the name of the only other Black physician in our program. Then I received a grading far below others. I strongly believe this was because I had told my attending that how she was asking questions—a process in medicine known as “pimping” where senior medical staff sometimes ask difficult questions during rounds to embarrass— was causing me to have panic attacks, amongst other instances of her biases playing out. I was called unprofessional for not wearing a tie, but I observed as white attendings would openly disparage me and other minoritized trainees. Only three months in I grasped that I’d chosen the wrong university.

Dr. Chase Anderson

Because I had managed my anger before and turned it into a powerful tool to shield me, I began to do so again. I mapped out what I could change. I worked on helping one senior staff member see how toxic the environment was, and a year after I began training they apologized for how they had purposefully ignored my words about discriminatory events, and for the hand they had in them. After that, we had weekly meetings where we spoke about how to change the training program to benefit minoritized trainees, and implemented many of those changes.

At the end of three years, I made the choice to graduate early and start my fellowship in child and adolescent psychiatry elsewhere. Now, almost a year into fellowship in California, I’m happy and I’m healing. Being at a university that supports my voice and who I am as a person, has changed my life.

Dr. Chase Anderson

That fury that was once overwhelming has mainly faded. There are times it flares, appropriately so: when I read about Asian Americans experiencing higher rates of depression and anxiety because of bigotry around coronavirus. When literary agents say that the memoir I wrote about medical school, to help the minoritized, “isn’t for them,” sometimes with racially-charged comments. Watching our government debate if people “deserve” a living wage. But, overall, my mind is calmer. I feel supported and I ride the wave when those moments happen. I remember that I can do something about some of these inequities; I can engender change. I have the strength and power to help other minoritized people have a different journey and a different relationship with anger.

I am now a qualified physician able to work with adolescents and kids around their anger and their feelings. We sit together and they learn how to navigate their rage in a space where they aren’t alone, where their anger is validated, and we speak about how to safely express their righteous ire. I have the opportunity to hold their feelings with them and help them figure out how to move forward while embracing all parts of who they are and how to stay safe in this world.

And that makes my personal journey eternally worth it.

Chase T.M. Anderson MD is a fellow in child and adolescent psychiatry at The University of California, San Francisco. You can follow him on Twitter @ChaseTMAnderson.

All views expressed in this article are the author’s own.

If you have thoughts of suicide, confidential help is available for free at the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline. Call 1-800-273-8255. The line is available 24 hours every day.