And in the weeks before they died on the Titanic, they were vacationing together in Europe.

“The enduring partnership of Butt and Millet was an early case of ‘Don’t ask, don’t tell,’ ” historian Richard Davenport-Hines wrote in 2012, referring to the policy that once required gay members of the military to keep their sexuality secret. A National Park Service page for the White House memorial fountain in their honor says they were “widely believed to have been romantically involved with one another.”

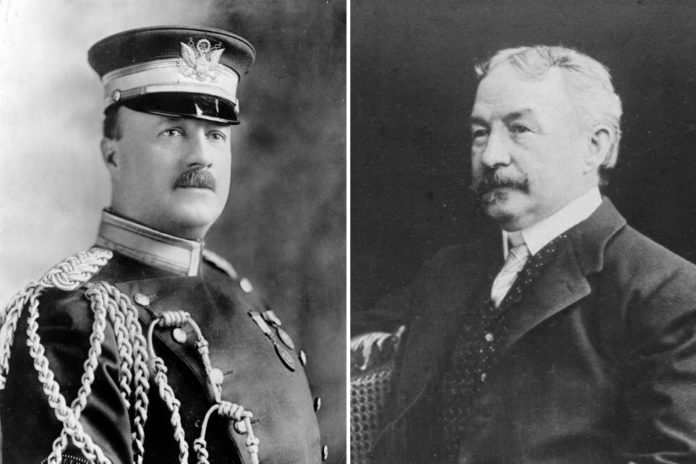

Millet was the older of the two, born into a well-to-do family in Massachusetts in 1848. As a teen during the Civil War, he served as an assistant to his surgeon father. He studied art at Harvard, then worked as a reporter as he traveled the world. He won acclaim for his murals at an art school in Belgium and for his writing as a war correspondent in the Russo-Turkish War. He and the travel journalist Charles Warren Stoddard exchanged love letters after a romantic affair in Italy.

He married in 1879 and had children with his wife, but as his career and profile grew, he mostly lived away from them.

Archibald Butt was born in Augusta, Ga., in 1865. His father died when he was a teenager, and as the eldest child, he was soon supporting his siblings and became very close with his mother. She moved with him to Tennessee when he left for college, and again when he moved to Washington, D.C., where he worked as a reporter for several newspapers and made a name for himself on the social scene.

At age 34, he joined the military and served as a supply officer in the Philippines and Cuba, where he rose through the ranks quickly after displaying an excellent aptitude for logistics. In 1908, he was recalled to Washington to serve as an aide to President Theodore Roosevelt.

He was brilliant at the job, organizing the president’s schedule and state dinners and even going with Roosevelt on his frequent hunting, climbing and riding excursions. When Roosevelt’s successor, William Howard Taft, took office, Butt stayed on. The two men became extremely close — most photographs from Taft’s presidency show Butt nearby, dressed in an immaculate and eye-catching uniform. Behind the scenes, he was a key negotiator on budget issues. According to the New York Times, Butt had memorized the names of 1,280 guests at a state dinner and introduced them all to Taft in one hour.

His social cachet extended outside his work. He lived with Millet in a Foggy Bottom mansion (now housing a George Washington University law clinic), where other bachelors occasionally rented rooms, and where Butt and Millet threw legendary parties. There were constant rumors that Butt was about to announce his engagement to the latest society girl, though shortly before his death, he told the Times he had been a bachelor so long that he “had better stay so to the end of the chapter.”

It is not known how Millet and Butt met, but the two were sharing the mansion and playfully arguing over its decor by 1910, according to Davenport-Hines. Butt was a prolific letter writer — a fact particularly important to Roosevelt and Taft biographers — but he rarely wrote of his personal life and referred to Millet as “my artist friend who lives with me.”

The last months of Butt’s life were stressful. His old boss, Roosevelt, and his current boss, Taft, had a public falling out, leading Roosevelt to run for president to unseat his former vice president. Butt felt torn between the two men, both of whom he greatly respected, and he had grown thin and pale and appeared run-down, a friend recounted later to The Washington Post. Millet urged Butt to take a vacation with him and rest, and when Butt demurred, Millett convinced Taft to order his aide to deliver a letter to the pope in Rome. Butt and Millet left for Europe in March 1912, sharing a stateroom on the ship Berlin.

They had separate rooms on the return voyage aboard the Titanic. At a brief stop in Ireland, Millet sent a letter to a friend praising the luxurious ship and complaining of “a number of obnoxious, ostentatious American women.”

It was the last anyone would ever hear from them. The ship hit an iceberg and began to sink. One survivor saw Butt standing near John Jacob Astor. Rumors of Butt escorting women onto rescue boats were later proved false.

When Taft learned of the Titanic disaster, his first thought was of his aide; early coverage in The Post focused on Butt and another prominent Washingtonian: “NO NEWS OF MAJ. BUTT OR CLARENCE MOORE,” an April 17 headline read.

The Washington Times quoted a friend who said “the two men had a sympathy of mind which was most unusual.” The Post said they were the “closest of friends,” comparing them to ancient Greek figures Damon and Pythias, who were willing to die for one another. Historian James Gifford, writing for OutHistory, suggested this comparison may have been an oblique way of signaling they were gay.

Millet’s body was later found; Butt’s was not. At a memorial service for Butt, Taft was meant to speak but became so overcome with emotion that he couldn’t continue.

Within weeks of their deaths, plans were underway to honor them with a White House fountain. The official reason was to honor the two Titanic dead who had been part of the federal government — Millet had a mostly symbolic role as vice chair of the U.S. Commission on Fine Arts.

Located on the southwest side of the White House near the E Street entrance, the fountain has a central pillar. On one side, facing south, is a male figure in bas-relief, with a helmet and shield, representing military valor (and presumably Butt). On the other side, facing north, is a beautiful woman with a paintbrush and palette, representing art (and presumably Millet).

A simple inscription reads: “In memory of Francis Davis Millet — 1846-1912 — and Archibald Willingham Butt — 1865-1912. This monument has been erected by their friends with the sanction of Congress.”