Also effective as of July: restrictions on the sports teams that transgender students can join in Indiana, South Dakota, Tennessee and Utah, and an Alabama law that echoes Florida’s “don’t say gay” law but also prevents transgender students from using bathrooms, lockers and other such facilities that align with their gender.

While school districts across the country are still months away from recognizing the full impact of these new policies, LGBTQ and civil rights advocates say they are alarmed. These laws could have a devastating impact on the mental health of LGBTQ students, a population that already has higher rates of depression and suicide, and could stoke a culture of fear and suspicion among students and school staffers, experts say.

What’s more, given how new these kinds of laws are, there is confusion among schools, community members and advocates about how they will be enforced.

These bills will have lasting effects on LGBTQ students, said Sam Ames, the director of advocacy and government affairs at the Trevor Project, which provides support to LGBTQ youths experiencing mental health crises. And the organization’s surveys suggest that these policies may already be having an impact as young people observe nationwide debates over their place in society.

Ames believes it is not a coincidence that so many education-focused bills came into effect at the same time. And, they added, the different bills will affect different aspects of young people’s lives — whether that is forcing a trans boy to use a girl’s locker room; forbidding a child to talk about how they identify or who they’re attracted to; or mandating that a girl deemed “too masculine” have their sex confirmed before they can play a team sport.

“The only thing that these [laws] really have in common is their target,” Ames said.

The lawmakers who have introduced these bills have argued that they’re meant to protect children, promote fairness and, in the words of Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis (R), push back on “woke gender ideology.”

South Dakota Gov. Kristi L. Noem (R) said the state’s ban on trans girls competing in female sports, the first such bill to be signed into law this year, would ensure “that girls will always have … an opportunity for a level playing field, for fairness, that gives them the chance to experience success.”

Ames and other advocates argue that, in reality, these bills will only harm students who already are vulnerable to discrimination and a lack of institutional and familial support.

Florida and Alabama’s laws banning classroom discussion also would require school staffers to report to parents if their children share that they may be gay or transgender. (This could also apply to students seeking counseling regarding depression, substance use or divorce, the New York Times reported.)

This would effectively force teachers and counselors, who may be the only affirming adults in LGBTQ kids’ lives, to out them to their parents, said Ames, an outcome that could endanger their safety. Research has shown that queer and trans young people experience parental abuse and homelessness at higher rates than their straight or cisgender peers.

“If we’re talking about forcibly outing transgender students to their classmates, parents and school staff, we are putting them in an enormous amount of harm’s way,” Ames said.

Other experts point out that cisgender students could be affected by some of these policies, which could encourage a climate of gender policing and distrust in school communities.

This is because of how vague and confusing some of these laws are, said Elizabeth Skarin, the campaign director at the American Civil Liberties Union of North Dakota, South Dakota and Wyoming.

For example, South Dakota’s law — which applies to all K-12 public schools and public colleges — bans trans girls from playing on female sports teams, but it doesn’t say anything about the teams on which transmasculine youths can play.

For Skarin, the law is not only “fundamentally unacceptable” in how it codifies discrimination against trans girls, but it is also unclear how it will work. This is true of similar bills in other states, she said.

“The laws are either poorly written or they’re unclear or they sort of leave open the door to questions, which is typically not what you want out of a law,” Skarin added.

Then, there’s the matter of enforcement.

The state of South Dakota itself will not be making sure schools follow with the law. Instead, it allows for private citizens to sue schools or school districts that they think are not complying with the ban.

“It’s really taking the power of the government and putting it in the hands of private actors to decide if they’re going to sue,” Skarin said. (This structure mirrors abortions bans in states such as Texas, which empowers private citizens to sue abortion providers for terminating pregnancies and also to sue any person aiding someone seeking an abortion.)

This kind of law also is notable because it could make it harder for the state to be sued for potentially violating the Equal Rights Amendment and Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, Skarin added. (The ACLU and the federal government argue that laws like South Dakota’s clearly violate both.) It could also be more difficult for the courts to block the law as it’s being challenged.

The South Dakota governor’s office has insisted that the law complies with the Constitution and is ready to defend the law in court.

Last year, Noem did not sign a similar bill into law out of concern that it could put the state at risk of litigation and spur a backlash from the NCAA. But the governor, who is running for reelection, championed the law this year. Her office amended the 2022 bill to say that the state would give legal representation and pay the costs of any lawsuits filed against the law, the Associated Press reported.

At this point, it’s unclear if and how parents and other community members will file such lawsuits.

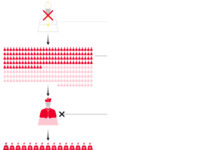

A 2021 Associated Press report found that among two dozen state lawmakers who introduced anti-trans sports bans last year, most could not cite a single instance of a trans girl’s participation causing problems. And Skarin said that because the number of trans girls who play sports is so low, it’s possible that these laws would more frequently affect cisgender athletes: girls who dominate competition or who appear aggressive or masculine, a dynamic that can affect Black women and girlsmore than their White peers, as well as queer student athletes.

The same issues are at play in Florida’s law, which bans instruction or classroom discussion about LGBTQ issues for kindergarten through third grade (and limits these topics in subsequent grades to “age-appropriate” instruction), and gives parents the right to sue schools if they think the law has been violated. The law is broad enough that it could be interpreted in many ways, said Kara Gross, the legislative director and senior policy counsel for the ACLU of Florida.

This not only could empower bigots, she said, but also will create a “chilling effect” among educators and school officials who are anxious and confused about what could be deemed inappropriate, and school districts, which would be forced to pay the cost of going to court.

Gross thinks the intent of these laws is to erase LGBTQ people and communities in as many ways as possible.

“[These bills] are all different pieces of the same puzzle, which is basically a nationwide attack on LGBTQ individuals,” she said.

But Ames, of the Trevor Project, said there’s still much that concerned parents, educators and community members can do to support LGBTQ students in the face of these bills.

Affirmation and acceptance go a long way, and simply using a child’s preferred name and pronouns can help prevent social isolation, depression and suicidal thoughts, experts say. And at a time when a nationwide mental health crisis is affecting millions of American children, schools also can put in place suicide prevention policies that are inclusive of LGBTQ students.

“If you have a young transgender person in your life … tell them what is happening is wrong,” Ames said. “Tell them that while these politicians might be powerful, control is different than strength. And these youth have shown time and time again that what they have is strength.”