Do you want to go back in time with SciFri? Sign up for the Science Friday Rewind newsletter to get more never-before digitized stories and audio bites from our archives!

Do you want to go back in time with SciFri? Sign up for the Science Friday Rewind newsletter to get more never-before digitized stories and audio bites from our archives!

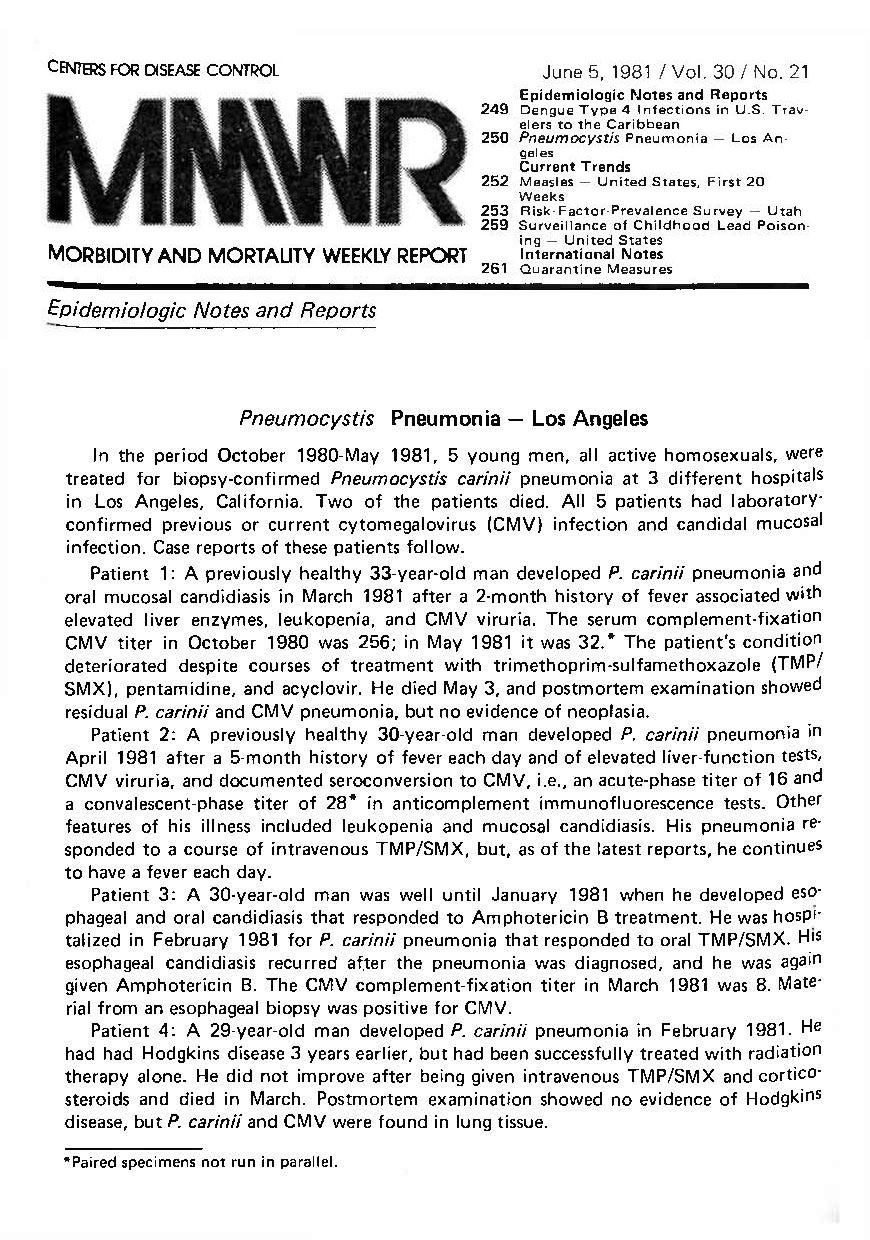

Every week, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) releases its regular report of the latest developments on emerging diseases—a living record documenting decades of medical history, known as the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR). In May 1981, former MMWR editor Michael B. Gregg got a call about an unusual deadly pneumonia, seen in young gay men in Los Angeles. The tip was from epidemiologist Wayne Shandera, Epidemic Intelligence Service Officer for the Los Angeles County Department of Health. He described the cases of five men, ages 29 to 36, who had developed Pneumocystis carinii, a kind of pneumonia typically seen in cancer and immunosuppressed patients. These men were previously healthy, yet they struggled to fight off the illness with treatment. Two of the patients died. All five were gay.

Gregg didn’t know what to make of the cases, but he and CDC experts were compelled to publish the observations in the June 5, 1981 issue of MMWR. Soon after, clinicians around the country began to flag similar cases. The number of infected people rose, as did awareness of the strange collection of symptoms. That summer, the media ran stories about the mysterious disease; the New York Times published the headline, “Rare Cancer Seen in 41 Homosexuals.” At that time, Ira was a science correspondent for NPR, and was in the thick of covering the nuances of the illness:

Archive Entry: December 10, 1981

Today marks 40 years since the first official report on the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the United States, and the beginning of a long-puzzling medical mystery. “I was totally baffled, and did not know what was going on. I thought it was a fluke,” recalls Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, during an interview this week with Science Friday.

“I made a decision literally when I was reading that horrifying MMWR,” he says. “I had never seen anything like this in otherwise healthy young people. And I said, ‘I’m going to change the direction of my research. And I’m going to study these young gay men who have this terrible disease.’”

Since the 1981 report, nearly 33 million people have died from AIDS-related illnesses. But over the last four decades, preventative healthcare and treatment options have helped reduce transmission. The development of various drug cocktail treatments and therapies have become effective enough for people with HIV to live long lives. This disease has undoubtedly changed the way the medical field approaches immune dysfunction, and has left a lasting impact on American culture.

Despite this progress, the HIV/AIDS epidemic continues. Thirty-eight million people worldwide currently live with HIV, as of 2019 data. Infection rates have declined among white gay men in big cities who were initially hit the hardest; the virus now disproportionately affects Black gay and bisexual men in the American South. The health crisis has deepened medical, cultural, and societal divides across the world—mirroring the disease disparities in Black, Latino, and Native American communities during COVID-19.

In an interview with SciFri in June 2020, Fauci reflected on the similarities between the uncertainty of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the HIV/AIDS epidemic. “There’s so many things that are analogous to what was going on when [we] were talking about it back in the early ’80s—the mysterious nature, the protean manifestations of disease,” Fauci said. “The more we learn about it, the more we realize how little we know.”

Archive Entry: April 20, 1982

In 1982, the CDC made its first mention of “acquired immune deficiency syndrome,” or AIDS, to classify the cases. By then, there had been nearly 600 cases of infection and 243 deaths. “There’s no question that it’s an epidemic,” Dr. Alvin E. Friedman-Kien, a dermatologist in New York City, told Ira for NPR’s All Things Considered on April 20 of that year. “But the question that one asks is: Why has this disease not been seen before? Why is it occurring now? And why is it occurring among this particular group of individuals?”

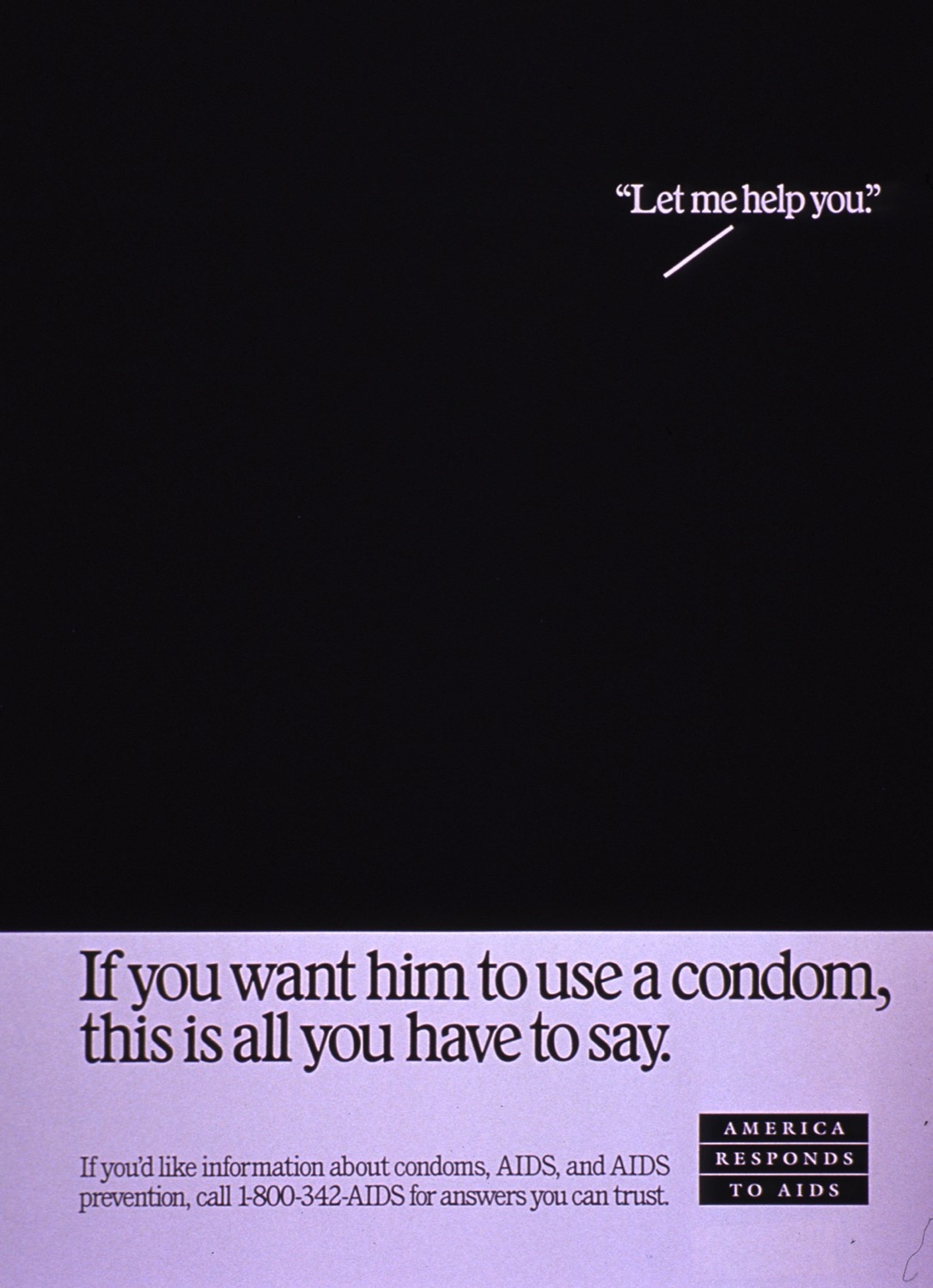

The initial outbreak of AIDS in the United States was largely seen in gay communities in urban centers, and later associated with drug users. The unknowns of the disease bubbled up discussions about sexuality, illicit drug use, and sexually transmitted diseases—conversations that many considered taboo in the 1980s and early 1990s. Society and the media wielded insensitive language that often blamed and alienated the gay community. When a patient tested positive for HIV, they not only had to battle a life-threatening disease, but the stigma that came with it.

Archive Entry: November 8, 1991, Science Friday’s First Broadcast

The week of Science Friday’s first broadcast on November 8, 1991, basketball icon and household name, Earvin “Magic” Johnson, publicly announced that he had tested positive for HIV. “I think sometimes we think, ‘Well, only gay people can get it, and it’s not going to happen to me.’ And here I am saying that it can happen to anybody,” he said on November 7. The news shocked the public, and left many divided. In the second hour of our very first show, we covered Johnson’s announcement, with dozens of callers voicing their opinions.

“I think it’s a little bit disingenuous when people react and the media reacts and politicians react like this is brand new news,” said one listener in San Francisco. Another caller who was an HIV patient, also from San Francisco, expressed frustration over the sudden shift in tone and attention from the public and media when “someone who is held up in public esteem as some kind of hero and idol” contracts the disease. “I admire him for the courage that he had yesterday in doing this, but there are heroes that have been fighting this goddamn war for the last 10 years. And they don’t get recognized.”

Magic Johnson’s pledge to fight the disease, and his vocal support towards education about it were an “important” turning point in the public’s perception towards AIDS and HIV, Fauci says in our recent SciFri interview. Johnson’s announcement opened up conversations about sex and sex education, and changed ideas of who were at risk of getting the disease.

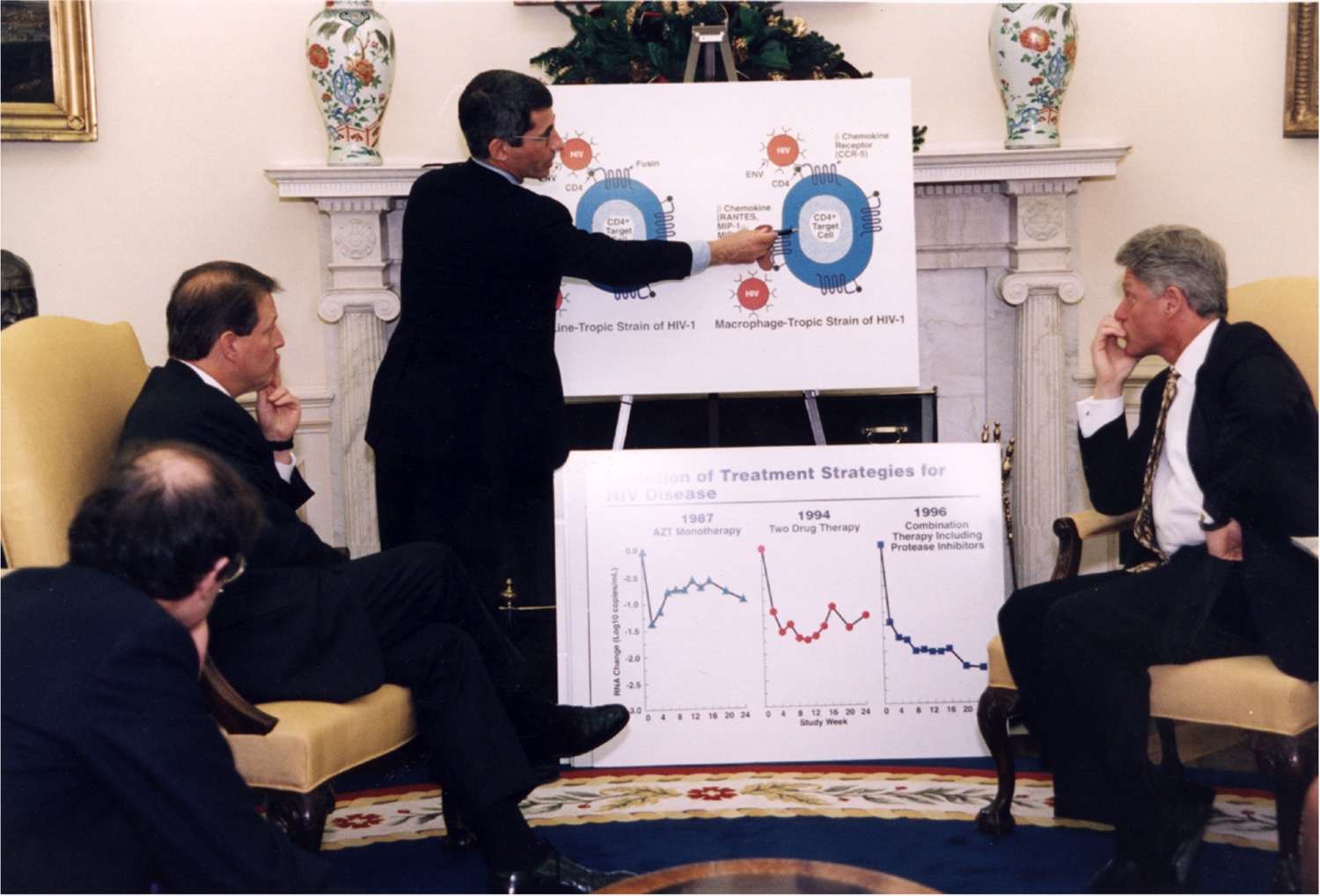

Archive Entry: July 29, 1994

In one of his first interviews on the show in 1994, Fauci described HIV as a “formidable foe,” an elusive invader for the immune system to fight off. The virus is able to weave its genetic material within human genes—covertly becoming a part of the cell it infects, and making it difficult for drugs to target. Back in 1994, Fauci explained that scientists first had to understand the “fundamental basics” of how the virus compromises the immune system in order to find effective treatment, therapies, or a future vaccine.

“As time goes by, we do understand more and more,” Fauci said in 1994. “The answer may not be around the corner, but the scientific advances come in a very stepwise fashion that don’t sound sexy, as it were, so people can read in the newspaper, ‘Wow, what a big, great advance this is.’ But it does take scientists and the science enterprise closer and closer to what the ultimate goal is.”

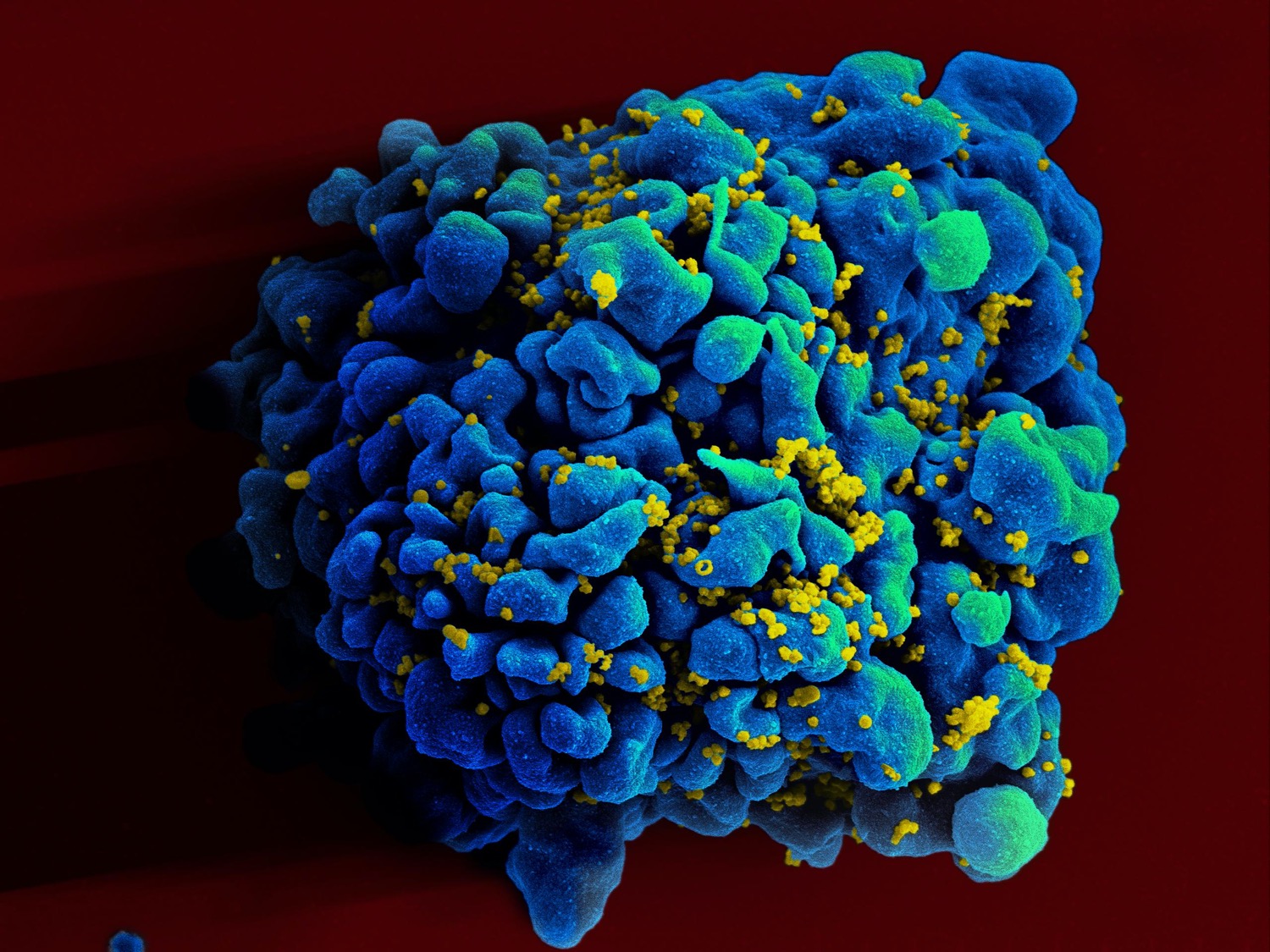

A flurry of research and policy changes in the 1990s and early aughts led to a better understanding of the virology of HIV, a retrovirus which infects specific cells in the human immune system and can deplete CD4+ T cells, causing AIDS. As scientists understood more about how the virus attacks and the clinical presentation of AIDS, they were able to develop tools like accessible testing, more effective active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), and the approval of Truvada for pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). Over time, this has turned HIV/AIDS into a treatable, chronic illness for some patients.

But communities that lack this essential care continue to struggle with the HIV/AIDS epidemic. The disease is a serious public health issue in many parts of Africa, Asia, and Latin America, while pockets of the United States also still see spikes in cases: “In some areas of the country, particularly in rural areas of the South, which are demographically overrepresented with African Americans, the stigma, the lack of access, all of those other factors have made it very difficult to have that kind of accessibility to all the things that you need to really stop the outbreak,” Fauci tells SciFri this week.

In 2019, the CDC reported that more than half of new HIV diagnoses in the U.S. happened in southern states, with African American men making up a disproportionate number of those cases. There are many factors driving the South’s HIV/AIDS epidemic, as Fauci explains—poverty, unemployment, lack of transportation, and not qualifying for health insurance all contribute to poor health outcomes. This inequality of care continues to be a challenge in combating infectious disease outbreaks today.

Archive Entry: February 19, 2021

Despite those systemic failures, other lessons from HIV and AIDS have proven helpful in furthering drug and vaccine development for other diseases. While scientists have still been unable to successfully create an HIV vaccine, the four decades of research and technology helped accelerate the development of the COVID-19 vaccine, Fauci says this week. “It seems a little paradoxical,” he says. “The types of elegant science that has evolved in an attempt, albeit thus far unsuccessful, to develop an HIV vaccine are technologies that have paved the way for the spectacularly successful COVID-19 vaccines.”

Still, Fauci is optimistic that COVID-19 vaccine research can pay it forward. “There are many HIV vaccinologists who are looking very closely at that platform technology to see if you apply the mRNA approach to HIV.” Fauci says. “I hope that what we’ve done with COVID-19 will help HIV.”

Find more SciFri stories and information—past and present—about HIV and AIDS below. And check out more archival stories from Science Friday Rewind.

Archival interview excerpts have been edited for length.

Further Reading

Donate To Science Friday

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Segment Guests

Anthony Fauci is director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases at the The National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland.

Segment Transcript

The transcript for this segment is being processed. It will be posted within one week after the episode airs.

Meet the Producers and Host

About Kathleen Davis

Kathleen Davis is a producer at Science Friday, which means she spends the week brainstorming, researching, and writing, typically in that order. She’s a big fan of stories related to strange animal facts and dystopian technology.

About Lauren J. Young

Lauren J. Young is Science Friday’s digital producer. When she’s not shelving books as a library assistant, she’s adding to her impressive Pez dispenser collection.

About Johanna Mayer

Johanna Mayer is a podcast producer and hosts Science Diction from Science Friday. When she’s not working, she’s probably baking a fruit pie. Cherry’s her specialty, but she whips up a mean rhubarb streusel as well.

About Ira Flatow

Ira Flatow is the host and executive producer of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.