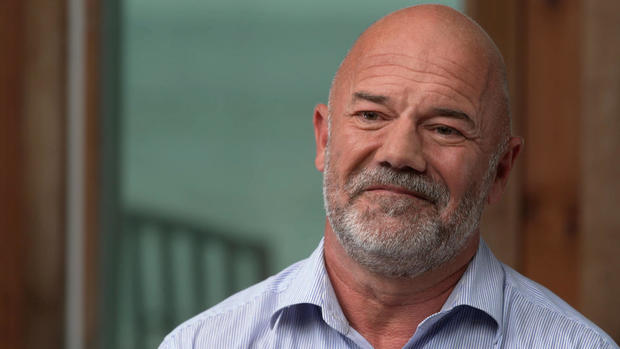

Andrew Sullivan has been an influential and controversial voice for more than 30 years. He’s a conservative author, editor and blogger. As a British-American, his style combines the perception of an outsider with the devotion of a native son. When we met, at his home on Cape Cod, we found Sullivan anxious about the future of the republic. Too many Americans, he told us, are no longer the citizens that the founders were counting on.

Andrew Sullivan: The American Constitution was set up for people who can reason and argue and aren’t afraid of it, and then reach compromises, the whole thing is designed that way. Well, if you’re in a tribe, and all that matters is the victory of your tribe, and you have all the truth, and your other tribe has none of it. And you have all the virtue, and the other side has none of it, you can’t behave that way. You can’t make it work. This country came to the point where we had violence in the usual peaceful transfer of power. That is a huge warning to how unstable our system can be if we remain tribalists in a system that’s supposed to be designed for reasonable citizens.

Scott Pelley: You know, we wring our hands about the strident nature of politics today. But hasn’t it always been that way?

Andrew Sullivan: Oh, yeah. There’s a lot of what you might call rough and tumble, sharp rhetoric. And that’s healthy. What’s not healthy is when that isn’t just retained and kept in the political area but becomes personal, becomes something you bring to the supermarket, becomes something you bring to Thanksgiving dinner, becomes something the permeates everything. And that separation between politics and life is what we’re losing. And that’s a terrible thing to lose.

Andrew Sullivan, 58, grew up in East Grinstead in rural, southern England. He won a scholarship to Oxford which led to Harvard and a Ph.D. in political science inspired by British conservative Michael Oakeshott.

Andrew Sullivan: And he defined conservatism as really a defense of what is. A love of what you already have. And fear that it could all disappear. A sense of the fragility of the world. And the importance of being pragmatic. Not having some ideological abstraction you wanna force onto reality. But understanding reality as something that can give you occasions for change, which we do need. But also warnings for excessive change and excessive radicalism.

Scott Pelley: In 2006, you wrote a book called “The Conservative Soul.” What were you saying?

Andrew Sullivan: I was saying that conservatism had lost its way. Because it had become too sure of itself. It was full of hubris. It believed it had the answer, the truth, became intolerant of liberals and of liberalism. And it became hardened by religious fundamentalism. Which brooks no compromise either. So, it broke the conservative virtues of humility, skepticism, doubt.

Scott Pelley: In the book you talk about rescuing conservatism. How do you go about that?

Andrew Sullivan: You wait for these terrible passions and the current cult worship of a human– individual human being, Donald Trump. You wait and hope that will pass. So that we can get back to the pragmatic process of governing reality. And that’s not what we’re engaged in now. We’re flying from reality. We’re inventing abstractions and ideologies. We’re fighting each other. We’re demonizing each other. The system can still work. It’s we who are broken.

The ideas of tolerance, reason and debate came to sullivan early in life when he realized he was conservative, catholic and gay.

Scott Pelley: You have written that you first acknowledged being gay while taking communion.

Andrew Sullivan: Yeah, I always, as a kid, had an intense spirituality. And as it welled up in me that I wasn’t like other boys, the only person I thought I could take it to was God. So, he was the first person I came out to. Just, “Please god,” I didn’t even have the word for it. But just, “Help me with that.” That’s why when people ask me, you know, “How can you be openly gay and Catholic?” My response is, “I’m openly gay because I’m a Catholic. Because I know God loves me. And I know that God would want me to tell the truth about myself.”

Scott Pelley: Is that dichotomy, Catholicism and homosexuality, the reason that you can hold two competing ideas in your head at the same time?

Andrew Sullivan: Well, I think it helps. One thing about coming out early and being honest about that, is that seeking truth and clarity becomes a habit. And you get a liberation from that. So, I said the truth. I thought the worst would happen. And I’m okay. So why can’t I tell the truth about other things or why can’t I just ferret it out?

Andrew Sullivan began ‘seeking truth’ in America in 1986. He needed a job and the left-leaning New Republic magazine offered him an internship. In five years, he was the editor. Sullivan was in a hurry because he expected to die. He was diagnosed with HIV in 1993.

Andrew Sullivan: The thing about that experience, was that, as you took care of people you loved who were dying very young in– and this is what people forget, in really horrible circumstances. Medieval tortures. Blindness, sores, lesions, neuropathy. The humiliation of it. And you know as I was doing that, that that’s gonna be me. That’s why I wrote the book “Virtually Normal, The Case for Gay Marriage,” because I thought I only had a few years left. And if I wanted to contribute something I would try and nail down the ironclad argument for marriage equality before I died.

Scott Pelley: But your argument at the time was that same-sex marriage should be a conservative goal.

Andrew Sullivan: Well, it should be, shouldn’t it? Why would supporting gay men in relationships not be conservative? Why would helping foster responsibility to take care of each other not be conservative? Of course, these are conservative values.

Sullivan married his husband, Aaron Tone, in 2007.

There have been six books including “I Was Wrong,” a compilation of his full-throated campaign for war in Iraq which he now regrets. Recently, in his blog “The Weekly Dish” and on his podcast, Sullivan’s weighed in on black lives matter and on critical race theory which says racism is systemic and perpetuates inequality to this day.

Andrew Sullivan: Here’s what I think is good about it. I think we should be absolutely vigilant about police abuse. And we’ve seen it. We’ve proven it to be racially targeted in some places, not all places. I think we’ve also too often whitewashed our past; whitewashed the true horrors of what it was to live in the segregated gulags of the South during’ slavery. In another sense, however, one of its key arguments is that the oppression of non-white people is the true, core meaning of this country. Now, I think it’s one important part to understand this country. But I don’t think it’s the most important part. And I don’t believe that it’s an accurate description of America today, I do think we’ve made enormous strides. I do think our racial panorama is much more complex and dynamic than it used to be. And I don’t believe this country’s fundamentally evil and needs to be dismantled.

Another controversy about race has followed Sullivan for nearly 30 years. Back in 1994, as editor of the New Republic, he ran an excerpt of the book “The Bell Curve,” which implied African Americans, genetically, have lower IQs. The excerpt ran 10,000 words. Sullivan printed rebuttals that ran 19,000 words. But he’s criticized for airing the debate at all. Scholars have since discredited the book. Sullivan has defended it.

Scott Pelley: You have written that the book has “held up,” that the book was “brilliant.”

Andrew Sullivan: The data is still there. We don’t know. And I think it’s been unfairly presented. The book is agnostic about the mix of genes and environment in terms of intelligence. And that goes for everyone. We don’t know.

Scott Pelley: But this raises a question in the viewer’s mind: Does he believe that African Americans are inherently less intelligent than white people?

Andrew Sullivan: Absolutely not. There’s no evidence for that.

Scott Pelley: Why was this an important debate to have

Andrew Sullivan: That’s a very good point, Scott. I’m not sure we should, to be honest with you. The debate was gonna happen, regardless. And I thought it would be helpful to have it put out in– in all its form; both the case for and then all the cases against. I thought that was a responsible way to respond to the emergence of this book and this piece. And I may have made the wrong call but I did it– I did it in good faith and I did it because I think it is always better to air this stuff than to suppress it, however feelings may be harmed. But I think if I were presented with that thing today, I wouldn’t. I’ll be perfectly honest with you, I wouldn’t. I think the harm outweighs the good.

He doesn’t mean he’s giving up on debate. He told us too many newsrooms, these days, pander to the left and right and are intimidated by political correctness.

Andrew Sullivan: When I ran The New Republic, it was a constant internal war. People felt passionate about subjects. One would write one week in one position. Another one would write the next week against it. And people would be fascinated by this internal struggle. I love that. I hate this feeling. I’m reading the church encyclical every week or every day and it’s telling me how I need to be perfectly woke or how I need to be perfectly ‘Trumpy.’

If the stakes for America seem personal in Sullivan, it helps to know he had to fight to be American. For 22 years, the U.S. banned citizenship to those with HIV. He argued against the ban which was lifted in 2010. Proof again, he says, of what can come of patience and reason.

Andrew Sullivan: We can fight over arguments but not debate each other’s good faith or character or dismiss people because of their race or sex or whatever. We can leave all that behind and be citizens, arguing, reasoning. Deliberation is what the founders called it. If we’re not like that, this system will fail as it is already failing.

Scott Pelley: So, what gives you hope?

Andrew Sullivan: Well, I would say there’s a difference between optimism and hope. I’m not particularly optimistic, given the trends that we’re seeing. But hope’s different. Hope is a sense that grace can happen. You never know what’s around the corner. Maybe there’ll be something in the future, a leader, a figure or there must be a sorta groundswell of people saying enough of this. Enough of this. The noise, the rage, it’s deafening and we’re better than this.

Produced by Aaron Weisz. Associate producer, Ian Flickinger. Broadcast associate, Michelle Karim. Edited by Matt Richman.