The global monkeypox outbreak is now a public health emergency both in the US and globally, with more than 38,000 cases currently reported across 93 countries as of August 17. Health authorities worldwide are still struggling to get it in check: According to the World Health Organization, cases increased by more than 19 percent in the past week.

They’re also struggling to figure out how to talk about what it takes to transmit the infection. During an Infectious Disease Society of America press briefing last week, the director of a large LGBTQ health clinic delivered what’s become a standard talking point among health authorities: “Skin-to-skin contact is causing transmission of this virus” in the context of sex, he said.

He wasn’t wrong, per se: The virus does spread most readily when one person’s skin is exposed to another’s open sores. But many officials seem hesitant to talk in detail about the role of penetrative sex between men — that is, body part-in-orifice sex, like anal and oral sex — in the current outbreak.

It’s part of a larger trend of health officials across the country being mealy-mouthed when it comes to clear risk communication. A story in the Washington Post referenced one state health department official who argued that “urging people to have less sex unfairly places the onus on individuals to end the outbreak,” which seems to minimize the options people have for reducing their infection risk. The official also argued that urging people to have less sex “distracts from other potential sources of transmission, such as dancing in packed clubs.”

Similarly, a New York City health department epidemiologist wrote of his employer’s unwillingness to publicly recommend sexual behavior changes that “we seem paralyzed by the fear of stigmatizing this disease.”

Many health officials’ reluctance to speak frankly might be coming from a well-intentioned place. As other journalists have noted, some of the vague-speak may be an effort to avoid giving ammunition to people who’d use gay and queer men’s sexual practices to demonize same-sex sexual contact and justify discrimination.

But unclear communication won’t stop this outbreak: People can’t take action to keep themselves safe from infections if they don’t know how they’re spread, and which behaviors appear most risky according to the latest data.

Gay and bisexual men — and the health organizations run by them, for them — have been at the forefront of offering clear communication about monkeypox risk reduction. It’s time for public health officials and the medical leadership who serve the general public to do the same.

Although clinicians and scientists in sexual health are engaged in a heated debate over whether monkeypox is a sexually transmitted infection, this is a semantic argument, and one that’s ultimately less important than helping people keep themselves safe. Making clear statements about the sexual behaviors most likely to spread monkeypox can help people across the spectrum of anatomy and sexual orientation understand how to protect themselves.

Let’s break it down.

Connecting the spots: Why scientists think sex is spreading monkeypox

As more data about this outbreak comes in, scientists are getting a clearer picture about how monkeypox infections start.

Scientists theorize that in people infected with monkeypox who develop a rash — as the vast majority of them do — the first spots turn up at the body site where the virus first made its way in.

This “inoculation site” theory is in part based on the way monkeypox infections have historically played out: For many infected people, the first symptom is a rash localized to one part of the skin or mucous membranes, which are the moist linings of openings like mouths, noses, vaginas, and anuses.

Several days afterward, these rashes are frequently followed by fever and aches. After that, a more widespread rash affecting other skin surfaces often develops. In both the first and third phases, the lesions of the rash are “chock-full” of virus, said Donald Alcendor, a virologist at Meharry Medical College.

Most experts believe the inoculation-site theory to be true, among them Chloe Orkin, an infectious disease doctor at Queen Mary University of London whose research group conducted a study describing 528 monkeypox cases in the United Kingdom. “We and others have speculated that the main site of the first lesion is likely to represent the point of inoculation,” Orkin wrote in an email.

A caveat: Some people involved in the current outbreak have had somewhat different experiences with monkeypox than the inoculation-site theory would predict. In one study, a third of cases did not report fever, and in some cases, the rash present in the third phase of infection has been pretty mild. These differences in the usual pattern of the disease make it harder to pinpoint the virus’s entry point, and it’s not clear what’s causing them.

However, cases in which the virus’s entry point can be identified paint an emerging picture: People are first getting infected during sex involving penises, mouths, and butts.

Most current monkeypox transmission is currently happening during sex

Before 2019, body parts involved in sex were not front and center in reports of monkeypox outbreaks. Then a publication describing a Nigerian outbreak noted large numbers of patients turning up with genital rashes. That study didn’t offer specifics of the exact location of genital rashes — but more recent studies have.

These studies get specific: They suggest that contact involving men’s mouths, penises, and anuses is responsible for the lion’s share of monkeypox spread right now.

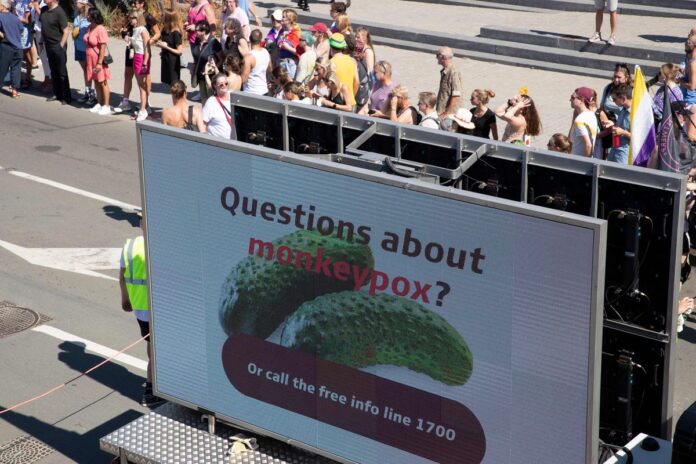

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23949952/GettyImages_1242479259a.jpg)

For example, in a recent Spanish study of 181 monkeypox cases, nearly all of whom were men, 55 percent of patients had genital lesions, 25 percent had lesions in or near their mouths, and 36 percent of patients had rashes around the anal area. (Many people in the study had lesions in more than one area, and were counted in more than one category.)

Orkin’s similar study of cases in the UK found 73 percent had a rash in the “anogenital area,” which includes both the anus and the genitals. A US study found that 25 percent of patients had lesions near their mouths. Across all three of these studies, 14 to 25 percent of patients have had proctitis, an extremely painful condition in which the tissues of the rectum — the part of the large intestine beyond the anus — get irritated and inflamed.

Reports of symptoms involving the anus, the mouth, and other mucous membranes have been particularly surprising, as they had rarely been reported with monkeypox infections during past outbreaks, said John Brooks, chief medical officer of HIV prevention division and the monkeypox response at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). “This real concentration in the anogenital region, which is where sexual contact occurs, and mucosal lesions — this is unusual,” he said.

Why are scientists so suspicious these rashes represent the places on the body where patients first became infected, implying sexual transmission? After all, the currently circulating monkeypox virus is genetically distinct from previous strains. Isn’t it possible one of its new features is a predisposition to causing genital rashes after first exposure elsewhere on the body?

They’re suspicious because of how commonly those rashes follow sexual activity involving the place where they appear. In the Spanish study, for example, 91 percent of people with proctitis due to the virus said they had been on the receiving end of anal sex, and 95 percent of people with symptoms in the mouth or throat said they’d given oral sex.

Again, what this suggests is that contact during anal and oral sex — potentially including “rimming,” or oral-anal sex — is responsible for the majority of monkeypox spread right now.

Sex can spread infections fast — and more sex can spread infections faster

The rapid spread of monkeypox seen during this outbreak is unusual for this virus. For example, Nigeria — the country with the highest burden of this monkeypox strain prior to the current outbreak — reported 915 suspected and confirmed cases in total between September 2017 and mid-June of this year. As many global cases are now recorded each day.

But for a sexually transmitted infection within interconnected sexual networks, where lots of people have sex with the same people, it’s not particularly surprising. “The more sexual partners one has, the higher the risk of exposure and transmission,” wrote Orkin. Cases in her group’s study reported a median of five sexual partners in the preceding three months. Again, this suggests that the current spread is not due to any old skin-to-skin contact, but due to sexual contact happening between people who have multiple sex partners.

It’s also not particularly surprising to see a lot of the spread happening at events and venues where sex is happening on site. At many of these venues, it’s not uncommon to have multiple partners in the course of hours at one event. And while overall, a minority of men who have sex with men use drugs during sex, that practice — often called “chemsex” — is more common at sex-on-site venues, and often leads to having more sexual partners. A third of people with monkeypox in the UK study said they’d gone to a sex-on-site venue in the past month, and the same proportion of cases in the Spanish study reported using recreational drugs during sex. So it’s not a stretch to speculate that drug use is a contributing risk factor here.

Even if attending these events is something only a small percentage of the world’s men who have sex with men do, it’s something that monkeypox cases have disproportionately reported doing, suggesting it’s an important risk factor. So should these sex events be canceled? There’s some disagreement among public health experts about the benefits of doing so, with some arguing it’s unhelpful at best and stigmatizing at worst to tell people — especially gay and bisexual people — not to have sex.

That said, people who want to avoid monkeypox will find it easier to do so if they avoid group-sex situations, at least until other precautionary measures are in place.

“We hate to say it, but it might be time to hang up the group sex and saunas until we all get shots one and two of the vaccine,” wrote the authors of a men’s safer sex guidance document, all of them public health practitioners. Both the World Health Organization and the CDC have recommended that people temporarily reduce their number of sexual partners.

Few women are getting monkeypox right now — but that doesn’t mean they can’t or won’t

Most monkeypox transmission in the current outbreak has happened between men — but women can still catch the virus.

Even though most men who have sex with other men don’t also have sex with people of other genders, a subsegment does: 11 of the men in the Spanish study reported vaginal intercourse, and six of the 181 patients in that study were heterosexual women. Although the study didn’t report the number of female cases who gave oral sex to men, there’s no reason that could not also result in monkeypox transmission from a man to a woman.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23949945/GettyImages_1242539668.jpg)

Although most of the transmission recorded so far has been between men, it’s probably not because the virus is better at infecting men. More likely, it’s a feature of how rarely gay men’s sexual networks include women.

“I would just be very careful about characterizing this as something unique to the kind of sex that men who have sex with men have,” said Brooks. Early in the HIV crisis, he explained, people thought that virus wouldn’t make many inroads with heterosexual people in the way it did with gay men. But in sub-Saharan Africa, HIV is now largely a disease that affects heterosexual people, he said.

Philip Chan, an infectious disease doctor at Brown University’s public health school who is medical director at the largest STI clinic in Rhode Island, agrees. He’s heard hypotheses that straight people don’t have lots of overlapping sexual partnerships the way gay and queer men and their sexual networks do, making heterosexual sex less likely to spread the disease broadly. “I’m not sure that’s entirely true,” he said.

Although monkeypox has not been transmitted at the same speed outside gay and queer men’s sexual networks as it has within them, that doesn’t mean it couldn’t happen. “If the virus is introduced into dense and active heterosexual networks,” like those involving commercial sex workers or swingers, “I think it would spread quickly,” wrote Orkin.

Using condoms — and temporarily changing sexual behaviors — could help prevent some of monkeypox’s worst symptoms

Many monkeypox studies now being published include photographs of the characteristic lesions in the many places where they’re appearing. Those photos often depict rashes on mucous membranes (inside mouths, throats, or anuses) — but many also show rashes around the openings to those spaces.

In other words, in many people with monkeypox rashes on their penises, the lesions spread well beyond the parts of the genitals that would be covered by a condom. It’s reasonable to imagine a barrier that only covers the shaft would do very little to prevent transmission from a person with a rash around their penis or around their anus.

Indeed, condoms haven’t been front and center among monkeypox prevention recommendations: Although the CDC’s guidance does mention condoms, many other messaging sources don’t.

But leaving condoms out of the conversation might mean neglecting an important strategy for preventing proctitis, one of the most severe monkeypox outcomes. If the inoculation-site theory is correct, this condition — which involves inflammation of the deep tissues of the anus — is more likely to happen when sores on a penis (or any virus in semen) have direct contact with those tissues.

Using that logic, putting a condom on a penis before anal sex theoretically makes that contact — and therefore proctitis — less likely, even if no scientific studies have supported that theory yet. (Rectal tissue is particularly fragile and the anus lacks natural lubrication, making the area especially vulnerable to tears and abrasions that create entry points for certain infections.)

During penis-in-vagina sex, condoms could also theoretically reduce the risk that an infected penis would cause lesions within the vagina.

In a press conference on August 11, Mary Foote, an infectious disease physician who directs emergency preparedness at the New York City health department, said there probably is a role for condoms in preventing some disease: “In a completely data-free zone,” she said, “I would say that using condoms certainly may help reduce the worst of it.”

Foote also noted that a significant proportion of newly diagnosed monkeypox cases are also being diagnosed with other sexually transmitted infections like syphilis, chlamydia, and gonorrhea — nearly a third of those described in the UK study, and 17 percent of those in the Spanish study. At a minimum, condom use could help prevent the transmission of those infections. Monkeypox alone is bad enough. Monkeypox plus an STI likely means more symptoms — and definitely means more antibiotics.

In addition to getting vaccinated, people can also reduce their risk by avoiding close sexual contact like kissing and oral, anal, and vaginal sex, especially with new sexual partners, wrote Debby Herbenick, a sexual health researcher and professor at Indiana University’s public health school, in an email.

Nobody wants to be telling people not to have sex right now. “It’s difficult timing, coming at a point in the pandemic where many people are vaccinated, boosted, and wanting to reconnect with others,” said Herbenick.

But she emphasized that changes in sexual practices wouldn’t have to be a new normal. “This is not about changing behavior forever — it’s for some limited period of time,” she said.