We all need myths to live by, and some of these stories we tell ourselves are ones we will cling to until the grave. In 1630, on the Arbella as it sailed toward North America, Puritan leader John Winthrop delivered a sermon called “A Modell of Christian Charity” asserting that this new land “shall be as a city upon a hill.” If that sounds familiar, it’s because on several occasions Ronald Reagan spoke of a shining city on a hill, sitting above other nations. Laying out an argument for American exceptionalism, Reagan claimed “that that there was some divine plan that placed this great continent between two oceans to be sought out by those who were possessed of an abiding love of freedom and a special kind of courage,” concluding at the very first Conservative Political Action Conference in 1974 that “we are indeed, and we are today, the last best hope of man on earth.” Of course, this kind of mythmaking requires an imperviousness to facts, a commitment to burying parts of our history, telling lies to ourselves and others to make them believe.

What does this have to do with our current predicament, the Covid-19 pandemic? Why reach back to the 17th century? Because our relationship to disease, to pandemics past, is obscured by this myth of fundamental American goodness. If we accept that we are capable of barbarity, official cruelty, these myths shatter and leave us with a national story that is far more complicated to tell, a legacy to work against; such acceptance brings us toward the need for truth and reconciliation, reparations and justice. It is no coincidence that the rise of American paranoia about critical race theory has emerged right now as an organizing tool for the Republican Party, an articulation of white grievance—a monumental fictional role reversal where white America is under threat from the black and brown. It also functions as a vaccine against the facts of the present, where hundreds of thousands of people lie dead from a virus at least partly because of political choices made by the same voters and those who represent them.

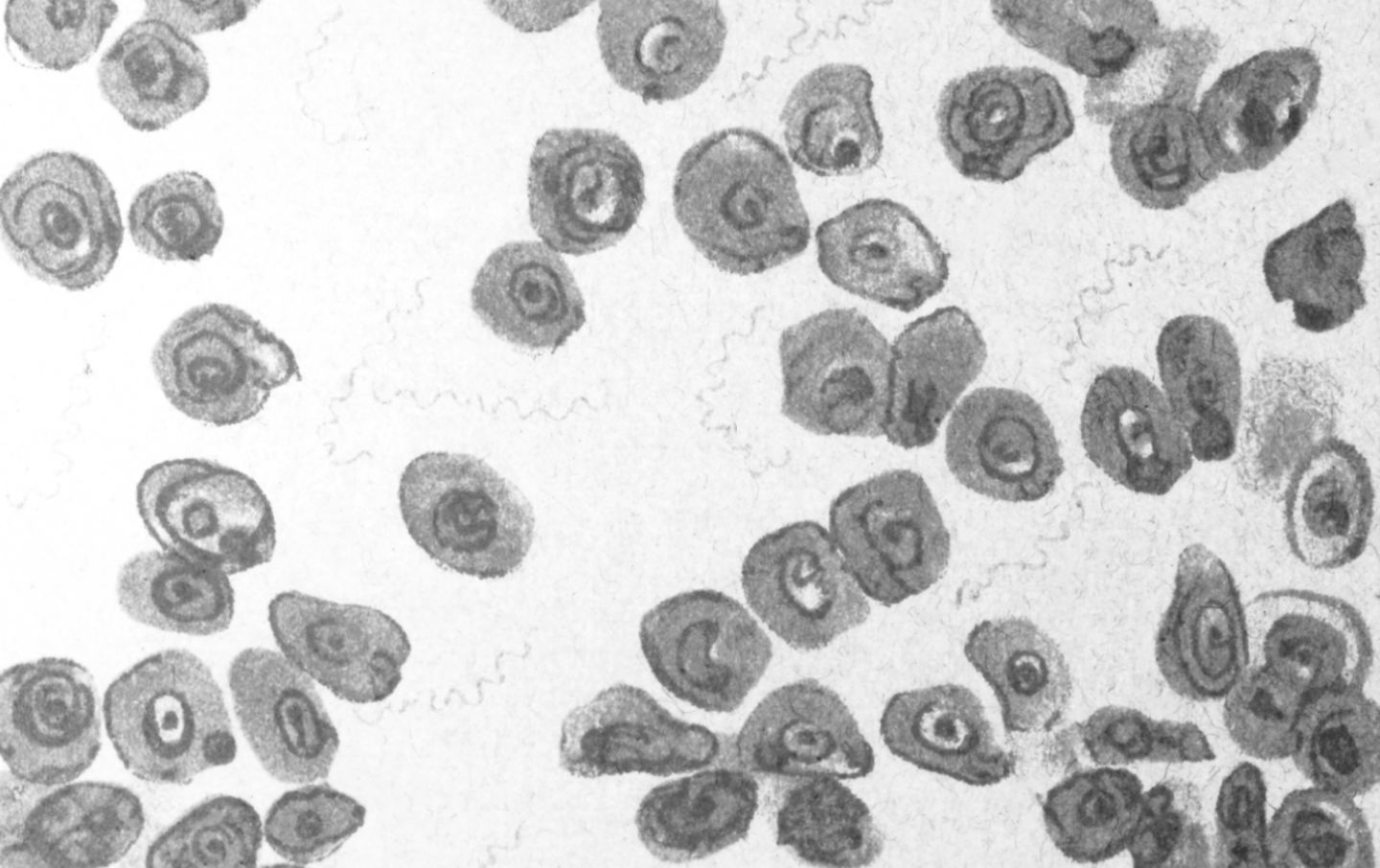

So let’s talk pandemics and pathogens. Those who work in public health are very familiar with the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment, a study of 600 African American men—a little more than half with a latent form of syphilis—who were deprived of treatment with penicillin for decades so scientists could observe the course of the disease. From the start of the study in 1932 to the discovery of penicillin as a treatment in 1947 to 1972 when the study was terminated “28 participants had perished from syphilis, 100 more had passed away from related complications, at least 40 spouses had been diagnosed with it and the disease had been passed to 19 children at birth.” The Tuskegee study stands as a cautionary tale, but it also is often the only story told about the intersection of American medicine and public health with white supremacy, as if it were an exception—a mistake, albeit a terrible one. But what if we see the Tuskegee study as part of a pattern that stretches back deep into our national past, and remains part of our pandemic present?

Only a century or so after John Winthrop’s voyage, the new colonists were at war with people whose land they had seized—the indigenous inhabitants of North America. That war was brutal, but so was the smallpox epidemic at the time, which afflicted colonists in their fortified outposts. At Fort Pitt, where today’s Pittsburgh now stands, Sir Jeffrey Amherst, commander in chief of British forces of North America during the French and Indian War, and for whom Amherst College is named, came up with a gruesome plan: “Could it not be contrived to Send the Small Pox among those Disaffected Tribes of Indians? We must, on this occasion, Use Every Stratagem in our power to Reduce them…as well as try Every other method that can serve to Extirpate this Execreble [sic] Race.” The idea was to infect the local indigenous population with smallpox via contaminated blankets.

We now turn New Orleans after the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. Here, infectious disease was mobilized not as a weapon but as an excuse, a rationale for the importance of slavery in the “heart of America’s slave and cotton kingdoms.” Yellow fever ran rampant, killing almost a tenth of the population each year. Stanford historian Kathryn Olivarius describes how the city’s elite “argued that they required large-scale black slavery—publicly proclaiming that black people were naturally immune to the disease based on spurious and racially-specific visions of medicine and biology,” even as they refrained from buying slaves who had not yet had the disease.

Another historian, Jim Downs, has written extensively on the intersection of colonialism, slavery, and war and infectious disease. His book, Sick from Freedom, describes a chilling phenomenon, that pandemics can disappear from the historical record, depending on who is getting sick, who is dying. Before he wrote, there was little record of the smallpox epidemic that swept the American South after the emancipation of the slaves and the end of the Civil War. Why? Because the disease largely decimated freed African Americans in the region and was considered a “black epidemic.” Thus, the outbreak was ignored and erased from history. The cholera epidemics of the time, however, largely affecting white Americans, were vigorously confronted and remain for us to read about now in narratives of the era.

We scrub history clean, we disinfect it, cleanse it of memories that conflict with myth. Just a few more examples. Who has heard of the 1917 bath riots? I certainly never had. In 1917, at the border between Mexico and the United States at El Paso, American health officials started fumigating workers crossing over into the city with kerosene and toxic chemicals. While a protest led by a 17 year-old woman named Carmelita Torres (we know little to nothing about her) shut down the border momentarily, the gassing of Mexicans crossing into the US in El Paso continued into the 1960s with agents such as Zyklon B and DDT, catching the attention of Nazi party leaders in Germany in the late 1930s. Hearing the words of Jose Burciaga, a janitor at the time, makes me shudder in recognition: “At the customs bath by the bridge…they would spray some stuff on you. It was white and would run down your body. How horrible! And then I remember something else about it: they would shave everyone’s head…men, women, everybody. They would bathe you again with cryolite [a pesticide]. That was an extreme measure. The substance was very strong,” Hard to accept in a country that sees itself as the shining city on a hill, but this is part of our legacy too.

These stories—painful to tell, to recollect, claim as our own—are horrible enough. We also have to confront the fact that this is the architecture—the scaffolding—upon which American medicine and public health are built. In the 1619 Project issue of the The New York Times Magazine, 389 years after John Winthrop’s sermon on the Arbella, an article by Jeneen Interlandi, a member of the Times editorial board, was headlined, “Why doesn’t the United States have universal health care? The answer has everything to do with race.” Interlandi describes how the history I’ve told you has left us with a fractured health care system, explicitly designed to exclude African Americans and other people of color from accessing medical help. In our own century, as we have fought to expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act, several states, many of them in the former Confederacy, have fought back to keep Medicaid expansions from happening or instituted work requirements to limit enrollment. Health journalist Anna Marie Barry-Jester has described how our history has imprinted itself on our present, how the maps of the density of slaves in 1860 in the United States reveal another pattern in the 21st century—of gross disparities in life expectancy, in deaths from diabetes, blood and endocrine diseases, from HIV, tuberculosis, and cervical cancer.

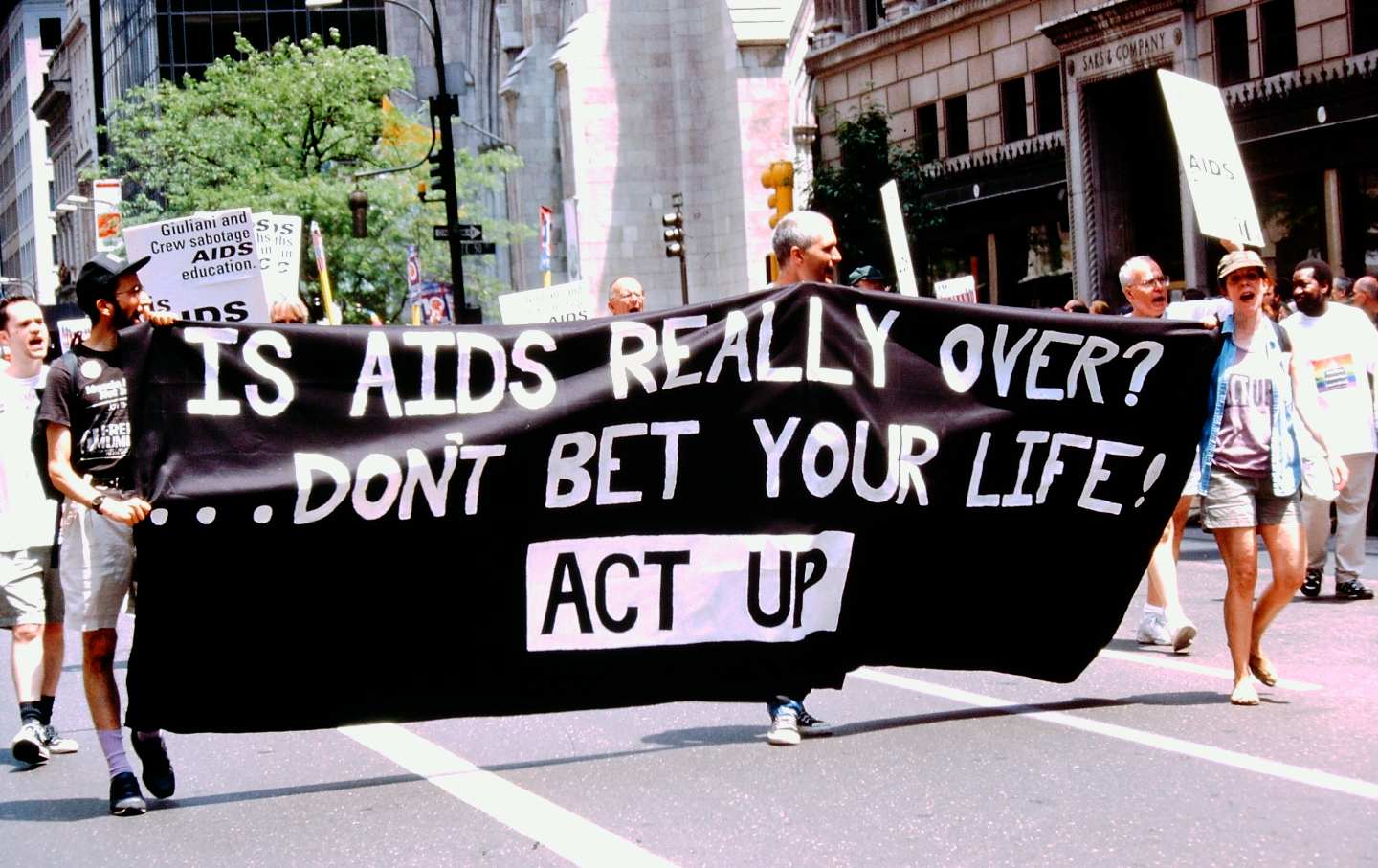

The late Larry Kramer, my comrade in ACT UP New York, once told a reporter that we were not “disposable people.” Despite his Yale education, his fame and relative wealth, Larry realized that he was disposable in the eyes of the state. The novelty of the AIDS epidemic was that you had white, often privileged, gay men like Larry being cast out along with people who used drugs, those in sex work, and communities of color ravaged by the disease. AIDS taught us that not many people count in our society; that our appetite for exclusion was boundless in this shining city on a hill.

I wrote here recently that the death toll from Covid-19 in the American South was no accident—that the patterns of deprivation and neglect that Barry-Jester described before the pandemic are being recapitulated today. We are in the midst of another epidemic of disposable people, with excess deaths among people of color far exceeding that of their white counterparts. But what I forgot to note is that our hunger for exclusion has entered a new phase—in which those with power have turned against their own constituents, as GOP leaders equivocate on the importance of vaccination to gain political advantage. The infections, hospitalizations, and deaths from the Delta variant have largely fallen on the unvaccinated in Trump-voting counties, with the ranks of the disposable now open to rural and small-town white voters and those in suburban areas that supported the former president and are some of the most hard-core vaccine refusers.

Who matters in America today? Follow the money. As wealth has grown increasingly concentrated, the ranks of those who matter in America seem smaller and smaller. And while the temptation is to blame the GOP, a Democratic senator like Joe Manchin from a poor state like West Virginia can moan about creating an entitlement society while sipping cocktails on his houseboat. Meanwhile reporters from The New York Times like Luke Broadwater and Michael D. Shear, Jonathan Weisman and Jonathan Martin paint the “problem” as progressives pushing for the president’s $3.5 trillion American Jobs and Families Plan. As my Nation colleague Joan Walsh puts it: Why can’t the media get this story right?

In fact, the president’s bill is popular, offers a once-in-a-generation chance to bring the United States up to code in terms of social protections, to extend benefits to many of “the disposable” in America and shore up the foundations of the safety net that can protect us against the next pandemic. But there is a deep investment in this country in the narrative of the deserving and undeserving—of those who matter and those who don’t. The story’s roots are in race, first in wiping out indigenous people, then in maintaining chattel slavery, and then in the continuing subjugation of African Americans after emancipation, creating a cordon sanitaire defined by ethnicity, sexuality, and gender (I didn’t get a chance to talk about sexually transmitted diseases, women and the Chamberlain-Kahn Act—go look it up), where the threat to “us” is always from the other—other than white, straight and male—and where the poor don’t count.

Nowadays that shining “city on a hill” from 1630 looks less like a beacon and more like a medieval castle, meant to protect wealth and power and those who can afford the privilege. In Edgar Allan Poe’s story “The Masque of the Red Death,” set in the midst of a plague, Prince Prospero seeks refuge from the pestilence within the walls of his great abbey, partying the nights away with his courtiers and friends, reveling in their safety. Finally, at an evening’s masquerade, a figure emerges in a shroud splattered with blood, enraging the prince, who chases him through the rooms of the castle. When Prospero finally confronts the figure, the prince himself falls dead. The interloper was the plague itself. The idea that we can wall ourselves off from others, subject them to unimaginable cruelty or simply malign neglect, and that we will be protected by our wealth and privilege is a myth to die by.

Walter Benjamin, who killed himself rather than be deported from Spain back to Nazi Germany, had a particularly tragic version of our collective fate. In his Theses on the Philosophy of History he wrote:

A Klee painting named “Angelus Novus” shows an angel looking as though he is about to move away from something he is fixedly contemplating. His eyes are staring, his mouth is open, his wings are spread. This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing in from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such a violence that the angel can no longer close them. The storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.

This story—its fatalism, its hopelessness—is a tempting myth to grasp for as we sit on the edge of another precipice. But perhaps it’s time to put the myths aside, to face the world we actually live in—not the world we aspire to. There is a task before us: the work of undigging. Digging out of our history—not to leave it behind, but to excavate it, display it for what it is, to learn its lessons and recognize how it can be deadlier than any virus.

The end of this pandemic—whatever form that will take—is not just about vaccines, masks, new drugs, and all the technical, biomedical tools we have at our disposal. It will take a realignment of cherished American values—values that are killing us. Likewise, avoiding the next pandemic—and yes, there will be one, even if we don’t know when—depends on realizing that we cannot go on like this. Such change requires an effort that transcends election cycles, bills to pass, pandemics to bring under control. It won’t be accomplished in a generation, but, as the old Talmudic sages said, “It is not your duty to finish the work, but neither are you at liberty to neglect it.” It’s time to put our “queer shoulder[s] to the wheel,” to shift the terms of the debate, to shatter the old myths, to be better than our history.

Editor’s Note: A version of this column was delivered as the Alan Berkman Memorial Lecture for the Columbia Mailman School of Public Health Epidemiology Grand Rounds.