It may be the most recognizable road in the world, even if Americans sometimes take it for granted.

The patchwork pavement of Route 66 still draws flocks of road-tripping vacationers (the majority of them from overseas, according to the proprietors of some Ozarks-area tourism stops) and figures prominently in the nation’s history and folklore.

In Missouri, the highway originated in Native American game trails and farm-to-market routes used during the first century of statehood, according to history compiled as part of a bid that won Route 66 designation as an “All-American Road” earlier this year.

The Mother Road inspired American art

Over its 95-year history, Route 66 has inspired some of the masterpieces of American artistic expression, including works like Bobby Troup’s classic jazz song “Get Your Kicks on Route 66” and John Steinbeck’s Great Depression-era novel, The Grapes of Wrath.

That book popularized the “Mother Road” moniker: “66 is the mother road, the road of flight,” Pulitzer Prize-winner Steinbeck wrote, as he described a farm family fleeing Dust Bowl Oklahoma in search of a better life in California.

But the contemporary impact of Route 66 goes beyond its origins in just one state, or works of art, some say.

“I think in the history of humankind there has never been a more recognized road as Route 66,” said Thomas Peters, dean of Missouri State University’s libraries, which have created extensive digital collections of Route 66 oral histories.

Even great roads from the ancient world, like the Silk Road that connected China to India and the West, don’t measure up to Route 66, Peters said.

He acknowledged that “bold claim” might raise eyebrows, but justified it this way:

“I sort of challenge people to stop a buddy, on a street of any city in the world, and say ‘Route 66,’” Peters said. “You will get a response of recognition.”

He added, “It’s like they’ve heard of it, even if they don’t quite know what it is. And it’s almost like more of an idea than a reality. There’s a reality there, but it’s become mythic.”

The “birth” of Route 66

The myth goes back to the history of the “birth” of Route 66 on April 30, 1926, a point of pride for many Springfield residents.

Peters said the most important Route 66 site in the Springfield area, the Colonial Hotel at the corner of Jefferson Avenue and St. Louis Street, is no longer standing. The Colonial likely hosted a fateful meeting between key Oklahoma and Missouri highway officials on that spring Friday 95 years ago.

At least some of the folks linked to the meeting were in town for a big Rotary convention that attracted thousands of attendees and their spouses, Peters said. According to the National Parks Service, downtown Springfield was “full of pedestrians (including roving bands of raucous Rotarians), cars, trucks, and streetcars.”

More:Pokin Around: A visit from an old friend cycling the Mother Road to collect COVID stories

A telegram sent from the downtown Postal Telegraph office to Washington, D.C. at 4 p.m. that day shows that state-level officials, squabbling with Kentucky’s governor over which states would get to use “60” — thought to be the best number for branding — settled on a compromise.

The new great road, which would begin beside Lake Michigan in Chicago, zipping 2,448 miles through Illinois, Missouri, Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas, New Mexico and Arizona before ending at an ocean overlook in Santa Monica, California, would be dubbed “Route 66.” Kentucky would be allowed to keep “Route 60” for another big highway.

Susan Croce Kelly, a former News-Leader reporter and Route 66 historian, writes in her book Route 66: The Highway and its People that the road’s advent in the 1920s came at a time when “travel by automobile was as much an adventure for many Americans as flagpole sitting or a solo cross-Atlantic flight.”

In the 1930s, Kelly wrote, the route became a key path for “destitute farmers and shopowners” — people just like the family portrayed in The Grapes of Wrath — who were pulling up stakes from the Midwest amid the Depression. During and after World War II, millions moved west on Route 66 to serve in the military or work in “West Coast armaments factories.” In the 1950s and ’60s, the road was beginning to show its age but remained a major thoroughfare for vacationers, many of whom were workers getting to take advantage of paid time off for the first time.

Motor courts were prominent feature of Route 66 life

Motor courts, usually a semi-circle of a half-dozen cabins for overnight lodging, placed near a central building “that’s like a one-pump gas station and diner,” Peters said, were a big feature of these decades in the life of Route 66.

There were so many motor courts in Missouri, Peters said, “at one point … if you spread them out evenly, there’d be more than one per mile.”

More:Little park pays tribute to Route 66 heritage

The best place near Springfield “where you kind of get a feel for what it was like” in Route 66’s heyday is west of town near Spencer, Peters said. That’s the stretch near Gay Parita Sinclair and other landmarks.

Across Missouri, there are other beloved marks on the map: Ted Drewes custard shop in St. Louis; the Munger Moss Motel in Lebanon; the Rail Haven, the Kentwood Arms and the Gillioz Theatre in Springfield, along with the first drive-through restaurant in the world, the original Red’s Giant Hamburg. (A modernized replica of Red’s was developed on West Sunshine Street, south of the original Route 66 alignment, launching in 2019.)

Less-well-known Missouri Route 66 landmarks include quirky places like a crumbling limestone building near Halltown that many people mistake for an old “casket factory,” but which was actually a store and a home, as the News-Leader reported in 2013.

Not everyone had a rosy experience with Route 66

Not everybody had a rosy experience with Route 66, of course. Peters notes that in the Route 66 era, road-tripping could be unsafe for Black Americans. Black motorists relied on the Green Book to navigate safe travel routes and avoid “sundown towns” that could be potentially deadly.

“You needed to think long and hard to plan where you were going to sleep, where you’re going to eat,” Peters said. For example, families took picnic baskets to avoid racism at restaurants, he said.

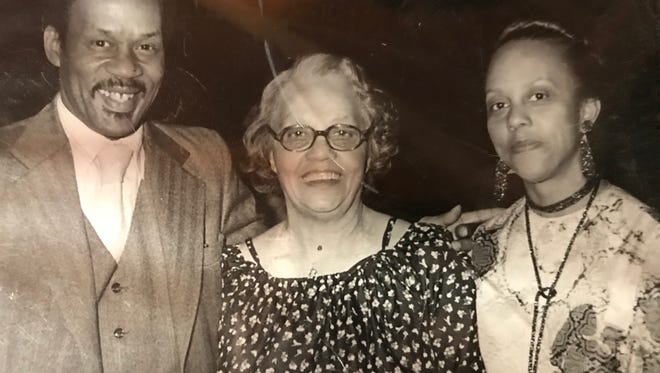

Springfield shared in that Jim Crow-era legacy, with at least two significant Black-owned businesses linked to Route 66. Entrepreneur Alberta Northcutt Ellis started a hotel on Benton Avenue and owned a snack shop. She served everyone. James and Zelma Graham did the same at their restaurant and motor court, near what is now Chestnut Expressway and Washington Avenue. Graham’s Modern Tourist Court served Little Richard, Ella Fitzgerald and Pearl Bailey when they performed at the Shrine Mosque, writes Joe Sonderman in his visual history, Route 66 in Missouri. The Grahams’ daughter, Elaine Graham Estes, was the first customer when the Route 66 Car Museum on College Street in Springfield opened in 2016.

Decades after the original Graham and Ellis businesses closed, the Route 66 era came to an end. In 1985, Route 66 was finally completely decommissioned by the feds. A few years later, the Route 66 Association of Missouri formed.

In 1990, Gov. John Ashcroft, a Republican from the Willard area, signed a bill “to the delight of Ozarkers who have come to know the stretch of the road as ‘America’s Main Street’,” the News-Leader reported at the time, making Route 66 in Missouri a 307-mile historic district.

That meant the road could be equipped with commemorative highway signs, similar to the ones that had been taken down five years earlier. To announce the change in Springfield, Ashcroft rode from the bill-signing ceremony in Waynesville in a 1961 Corvette, much like the one featured on the ‘60s-era “Route 66” TV show, the News-Leader reported at the time.

Reach News-Leader reporter Gregory Holman by emailing gholman@gannett.com. Please consider subscribing to support vital local journalism.