The way Rasheed Newson tells it in his debut novel, My Government Means to Kill Me, set in 1980s New York City, the AIDS activist group ACT UP didn’t spring into existence after a rousing call to action by writer Larry Kramer during a speech at the LGBT Community Center. Nope. That narrative, commonly recounted today, amounts to a myth, a “lie [that] has a romantic sweep to it, if one finds beauty in the magic of accidents and perfect timing.” Instead, Kramer enlisted the help of civil rights leader Dorothy Cotton, who worked with Martin Luther King Jr., and the two secretly trained an AIDS army, going so far as to hire goons to rough up wannabe activists to see who could take the impending abuse.

Did that really happen? Hardly. But the novel is a work of historical fiction. Many of the people and events are real, but others are fabricated. It’s the clever tale of 18-year-old Trey, a Black gay man from the Midwest who comes of age in the heady world of HIV activism in New York City.

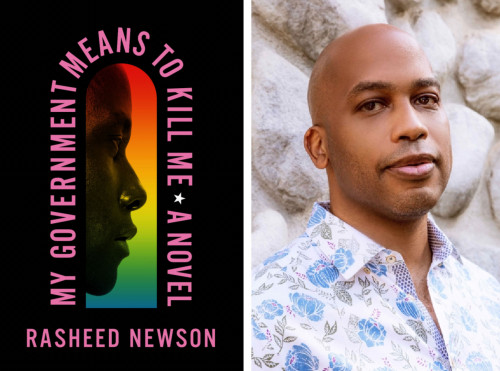

Author Rasheed Newson and his debut novel(“My Government”): Flatiron Books; (Newson) Courtesy of Christopher Marrs

To learn what’s fact versus fiction in his book, we spoke with Newson, 43, as the married father of two was prepping for the new season of Bel-Air. He’s the showrunner and executive producer for the TV series (a dramatic reimagining of the ’90s sitcom The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air). He has also worked on the series Narcos, Shooter and The Chi. Our conversation has been edited for clarity and brevity.

When did you first learn about HIV?

In high school, in 1994, a teacher brought in a man who was HIV positive to speak to us. I was 15. It was a revelation. He has to have been the first person I ever knew who openly had HIV. I remember him being led into the room because at that point his vision was such that he could only see us as a shape or silhouette. Incredibly powerful.

Did you come out at a young age?

I was not terribly brave [about coming out early], but I was also not fooling anyone. I never had a serious girlfriend and was on the down low dating other boys my age. When I did come out after college, I don’t remember anybody gasping.

You grew up in Indianapolis (like the novel’s protagonist, Trey). You went to college at Georgetown University in Washington, DC, and you now live in Pasadena, California. What drew you to writing a story set in New York?

An uncle, who is gay and only 14 years older than me, lived in New York City. Ever since I was 16, I would fly out there once or twice a year to see Broadway shows and hang out. We’d tell my parents that [my uncle] was taking the day off, but he was a lawyer so wasn’t missing work. [I explored on my own] and loved it. Just to show you where I was in my life, of all the things you could do, I once figured out how to take the subway to Brooklyn where they filmed [the soap opera] Another World so I could stand outside and see, like, Linda Dano walk in.

Were you involved in AIDS activism?

I volunteered at Grandma’s House [a home for foster care children living with HIV]. I’d help them with homework and be a playmate. Teachers and students were afraid of them, so our job was: I’m gonna love you like mad, and somebody’s going to think you’re the best thing ever.

In my nonprofit life, I worked for the Coalition for Juvenile Justice. In college, we’d protest against the death penalty. [That activism was] very much like the AIDS activism that I wanted to convey in the book: Yes, the subject is heavy, but protesting wasn’t somber. We’d joke around, and somebody cute would be there, and you’d get their number. You’d get to be friends with these people. That’s the vibe I want to remind everyone of.

Your novel melds AIDS activism with civil rights history. What’s the link?

By the time you get to the ’80s, you’ve got people who’ve been in the civil rights movement, the women’s rights movement, the anti–Vietnam War movement. You have older people who are like, “I know who to call to get the Times interested in this story” or “This is how systems work and how change is brought about.” And then you have young people who are willing to throw their bodies into the movement and bring passion but are impatient. I think there has to be that push-pull. I’m all right with the clash and the messiness.

Many novelists play with facts to get at underlying truths or to streamline a story. You include footnotes that explain historical people and events, but do you worry that readers might not know what’s fabricated?

Oh, this is historical fiction. As long as I gave you some indication of where you could follow up on the facts, I thought it was fair game. And in a few footnotes, I’m telling you I’m making this up. I’m trying to be openhanded about when something is real and when it’s not. But all the other [nonfiction] material is still out there for the taking. And at the end of the book, I give a reading list, like Sarah Schulman’s Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP New York.

And I’m hoping that [my fictionalized version] brings in younger people, that people who lived through [1980s AIDS activism] can get a sense of nostalgia and that this rings authentic, even if it’s not factually true.

Bayard RustinWikimedia/Library of Congress

Let’s clarify some details. Trey befriends civil rights icon Bayard Rustin, who holds court at Mt. Morris Baths, a real-life bathhouse that catered to Black gay men. What do we have there?

The facts cater to Rustin’s demographic. I know Rustin was [arrested and convicted] in Pasadena, California, in 1953, for sexual activity with two men in a parked car. What I took from that was: Oh, right, you know a lot of things about Rustin, but he is a man, a gay man, with sexual desires at a time when those desires were criminalized. So I thought, Let’s continue the idea that he was still sexually active.

Did Dorothy Cotton and Larry Kramer work together to train AIDS activists?

Not that I know of. But she was for gay rights and marriage equality. And she had done trainings—that really was her talent. The idea of those lunch counter trainings back in the day [to prepare for the 1960 nonviolent sit-ins to protest segregated lunch counters], they knew they’d have hot coffee poured on them and people would get in their faces and scream, so without trying to do real harm [the trainings aimed] to simulate the chaos and instill how to stay calm and self-possessed.

Dorothy CottonYoutube/Library of Congress

Did ACT UP members subject themselves to these physical trainings at Kramer’s apartment?

I know there were people at Larry Kramer’s apartment at the beginning of ACT UP organizing, but what happened there? That’s my invention. I did a lot of research, and almost everything was possible with ACT UP because each branch did its own thing. What I encourage other people to do—whether it’s to learn about Kramer or Rustin or Dorothy Cotton—is go online because there are hours and hours of video and audio of them talking about their lives.

Larry Kramer was alive when I started this book [he died May 2020], and a friend asked if I wanted to talk with him. I said, “I absolutely do not want to talk with Larry Kramer. I’m frightened of Larry Kramer.” But if I did, then it would get in my head in the wrong way, and I’d be stuck with whatever he tells me.

Larry KramerEthan Hill

Another main character is Angie, who runs an AIDS hospice that mostly caters to dying Black gay men. Is she based on a real person?

She’s a composite of all the lesbian sisters who stepped up during the crisis and who disappear from our stories of, like, five white guys holding hands on the beach facing AIDS. I’m not saying that didn’t happen, but there are other stories. Ultimately, this is the story of an enduring friendship between a femme gay Black man and this unapologetic butch lesbian, and I was happy with that.

Do you consider yourself an activist?

I was much closer to it when I was in my 20s and could go to protests. Now I consider myself an activist in how I’m raising my children. I certainly use my dollars and donations for liberal causes. And I consider writing this book an act of activism.