By Karen Ocamb | LOS ANGELES – In the beginning, the deaths and disappearances were isolated, frightening but shorn of consequence, like short, scattered tremors before a massive earthquake. Gay San Francisco Chronicle reporter Randy Shilts suggests in his extraordinary AIDS history “And the Band Played On” that the mysterious contagious disease that would claim the lives of millions silently exploded when sailors in ships from fifty-five nations came to New York Harbor on July 4, 1976 to join thousands celebrating America’s bicentennial.

Then death came home. Hugh Rice, director of the STD Clinic at the Los Angeles Gay and Lesbian Community Services Center during the height of the Disco era, recalled a very sick young, thin penniless gay man covered in purple lesions in 1979 who came in for his STD shot, disappeared, and died six weeks later in isolation at LA County Hospital. Matt Redman, the interior designer and disco fan who co-founded AIDS Project Los Angeles, suspected he had been infected with HIV in the late 1970s.

But it wasn’t until L.A.-based Dr. Michael Gottlieb and colleagues authored a report published June 5, 1981 in the Centers for Disease Control’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly that identified the mysterious illnesses that would become known as AIDS.

At the time, Gottlieb was a 33 year-old assistant professor at the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) Medical Center specializing in immunology who was fortuitously curious. He asked a postdoctoral fellow to go to the wards and ask interns and residents if there were any patients who had interesting immunologic conditions. He found medical intern Robert Wolf, whose patient Michael had been admitted to the UCLA emergency room in January with fevers, some fungal infections on his skin, a 25 pound weight loss, and a mouth full of thrush, or candidiasis. Additionally, Gottlieb obtained a still experimental blood test looking at Michael’s T-cells that revealed that his CD4 (“helper cells”) “had essentially gone missing.

“This was a unique finding. We had never seen anything like this in any other immunologic or in any other medical condition,” Gottlieb tells the Los Angeles Blade.

Michael was discharged from the hospital but returned a week or two later with a lung infection.

“He came back to Robert Wolf. Ordinarily, you would not do a bronchoscopy for a community acquired pneumonia — ordinary bacterial pneumonia. But Robert astutely said, ‘you immunologists are telling us that this man is immune deficient. He is an immune-compromised host. We therefore should do a bronchoscopy (an invasive procedure) to be sure he might have an opportunistic infection. And indeed, he had pneumocystis pneumonia. So that’s the story of patient number one,” says Gottlieb.

“Michael was a model. He had bleached hair. He looked like a rock star. A few months later, he developed a large lesion of Kaposi’s sarcoma on his chest. And that was a mystery also. He died within the first six months of his first emergency room admission,” Gottlieb says. Michael also “happened to be gay.”

Sexual orientation wasn’t a specific consideration until Gottlieb got a call from Dr. Peng Fan, who was the acting chief of Rheumatology at the Wadsworth VA in Los Angeles. He had been moonlighting at Riverside Hospital where Dr. Joel Weisman and Dr. Eugene Rogolsky had been admitting patients from their gay practice, two of whom had similar symptoms to Michael. They were transferred to the respiratory care unit at UCLA.

Pulmonary doctors immediately performed bronchoscopies “and low and behold, these two patients also had pneumocystis pneumonia. And now we had three gay men with pneumocystis pneumonia and absent CD four cells. That’s when we said, ‘oh, we have three gay men with pneumocystis pneumonia. That was the moment,” he said.

Gottlieb called the editor of the New England Journal of Medicine and asked for his advice on how to publish their findings there. “And he said, ‘well, have you spoken to CDC?’ As an immunologist, my orientation was not toward the CDC — infectious disease doctors are oriented toward the CDC. But I wasn’t an infectious disease doctor. So I said, ‘no, I haven’t.’ And he said, ‘well, maybe you ought to.’ So I called Wayne Shandera, the CDC person in Los Angeles assigned to the LA County Health Department as an epidemic intelligence service officer. I knew him from my time at Stanford because he was there as well. And I said, ‘Wayne, are you aware of anything unusual going on among gay men in Los Angeles or anywhere in the country?’ And there was an eerie silence on the other end of the phone. And he said, ‘no, but I’ll look into it.’ I told him, we think it might have something to do with the virus called CMV cytomegalovirus.’”

Shandera found some CMV growing from a patient sample from Santa Monica. “He went down to Santa Monica hospital and spoke to the patient and indeed, it was a gay man with pneumocystis, pneumonia and CMV as well. And so he unearthed a fourth patient,” says Gottlieb.

It was after Gottlieb’s fifth patient, Randy, referred to him by a doctor at Brotman Hospital, that he decided it was time to write up a report for the CDC, with a more explanatory article published later in the New England Journal. He sat down at Shandera’s dining room table in the Fairfax district and typed up the report on an IBM Selectric typewriter, after which it was sent it off to CDC.

The editor of the CDC’s MMWR returned it with some modifications and corrections. “Interestingly, we called it ‘Pneumocystis Pneumonia Among Homosexual Men in Los Angeles.’ The CDC changed the title to ‘Pneumocystis pneumonia, Los Angeles.’”

Gottlieb doesn’t see anything nefarious in the change since the MMWR was focused on disease outbreaks like the salmonella outbreak in Idaho. Additionally, “if CDC had called it Pneumocystis Pneumonia Among Homosexual Men in Los Angeles,’ it might’ve even worked against us,” says Gottlieb, “although, ultimately, it got characterized as a gay disease anyway.”

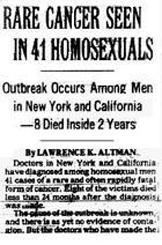

“The cause of the outbreak is unknown, and there is as yet no evidence of contagion. But the doctors who have made the diagnoses, mostly in New York City and the San Francisco Bay area, are alerting other physicians who treat large numbers of homosexual men to the problem in an effort to help identify more cases and to reduce the delay in offering chemotherapy treatment,” Lawrence K. Altman reported. “The [violet-colored] spots generally do not itch or cause other symptoms, often can be mistaken for bruises, sometimes appear as lumps and can turn brown after a period of time. The cancer often causes swollen lymph glands, and then kills by spreading throughout the body.”

The next day, July 4, 1981, the CDC reported 36 more cases of KS and PCP in New York City and California, linking the two coasts. The following month, the CDC reported 70 more cases of KS and PCP that included the first heterosexuals and the first female. By December, when Gottlieb’s New England Journal article was finally published, the CDC reported the first cases of intravenous-drug users with PCP. But also, by then, the media had painted the mysterious new diseases as Gay-Related Immunodeficiency Disease (GRID) or as it was more commonly called: the “gay plague.”

Editor’s Note:

This is Part One of a series looking at the 40th Anniversary of AIDS. Part Two looks at the panic, confusion and efforts to fight the mysterious disease in the face of intentional government neglect; Part Three looks at Gottlieb, Rock Hudson, Elizabeth Taylor and founding of amfAR; and Part Four covers Clinton to COVID.

Karen Ocamb is the Director of Media Relations for Public Justice, a national nonprofit legal organization that advocates and litigates in the public interest.

The former News Editor of the Los Angeles Blade, Ocamb is a longtime chronicler of the lives of the LGBTQ community in Southern California.