By Karen Ocamb | LOS ANGELES – Before the CDC’s first report on AIDS, there was news from the New York Native, a biweekly gay newspaper published in New York City from December 1980 until January 13, 1997. It was the only gay paper in the City during the early part of the AIDS epidemic and it pioneered reporting on AIDS.

On May 18, 1981, the newspaper’s medical writer Lawrence D. Mass wrote an article entitled “Disease Rumors Largely Unfounded,” based on information from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention scotching rumors of a “gay cancer.”

“Last week there were rumors that an exotic new disease had hit the gay community in New York. Here are the facts. From the New York City Department of Health, Dr. Steve Phillips explained that the rumors are for the most part unfounded. Each year, approximately 12 to 24 cases of infection with a protozoa-like organism, Pneumocystis carinii, are reported in New York City area. The organism is not exotic; in fact, it’s ubiquitous. But most of us have a natural or easily acquired immunity,” Mass wrote. He added: “Regarding the inference that a slew of recent victims have been gay men. . . . Of the 11 cases . . . only five or six have been gay.”

Eighteen days later, on June 5, 1981, the world turned when the CDC published an article by Dr. Michael Gottlieb in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) on AIDS symptoms, including cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection and candidal mucosal infection, found in five gay men in Los Angeles. By then, 250,000 Americans were already infected, according to later reports.

Gottlieb’s CDC report was picked up that same day by the Los Angeles Times, which published a story entitled ”Outbreaks of Pneumonia Among Gay Males Studied.” A slew of similar reports followed and on June 8 the CDC set up the Task Force on Kaposi’s Sarcoma and Opportunistic Infections to figure out how to identify and define cases for national surveillance. On July 3, the CDC published another MMWR on pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP) and Kaposi’s Sarcoma (KS) among 26 identified gay men in California and New York. The New York Times’ story that day — “Rare Cancer Seen in 41 Homosexuals” – stamped the disease as the “gay cancer.” GRID (Gay-Related Immune Deficiency) came next. In the new Reagan/Bush Administration, dominated by homophobic evangelical advisors such as Gary Bauer, funding to investigate the new disease was scarce.

Two years later, the New York Times finally put AIDS on the front page, below the fold, with a May 25,1983 headline that read: “HEALTH CHIEF CALLS AIDS BATTLE ‘NO. 1 PRIORITY.’” By then 1,450 cases of AIDS had been reported, with 558 AIDS deaths in the United States; 71 percent of the cases were among gay and bisexual men; 17 percent were injection drug users; 5 percent were Haitian immigrants; 1 percent accounted for people with hemophilia; and 6 percent were unidentified.

But Health and Human Services Assistant Secretary Dr. Edward N. Brandt Jr. told reporters that no supplemental budget request had been made to Congress. ”We have seen no evidence that [AIDS] is breaking out from the originally defined high-risk groups. I personally do not think there is any reason for panic among the general population,” he said.

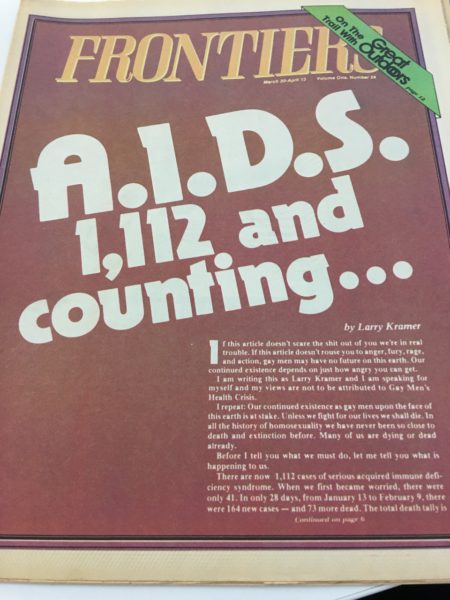

Gays in denial seemed to accept feigned governmental concern. Others were deathly afraid. The HHS news conference was just 10 weeks – and 338 more cases – after the March 14 publication of playwright Larry Kramer’s infamous screed on the cover of the New York Native: “1,112 and Counting…”

“If this article doesn’t scare the shit out of you, we’re in real trouble. If this article doesn’t rouse you to anger, fury, rage, and action, gay men may have no future on this earth. Our continued existence depends on just how angry you can get,” Kramer wrote. “I repeat: Our continued existence as gay men upon the face of this earth is at stake. Unless we fight for our lives, we shall die. In all the history of homosexuality we have never before been so close to death and extinction. Many of us are dying or already dead.”

Too many gay men were not scared shitless. When LA gay Frontiers News Magazine re-published Kramer’s article as their March 30 cover story, bar owners threw the publication out, lest it unnerve patrons. Meanwhile, gay men wasted away and died, often alone, sometimes stranded on a gurney in a hospital hallway; sometimes – if lucky – with family or friends crying at their bedside as in the intimate photo taken by Therese Frare as her friend AIDS activist David Kirby died.

None of this was new or startling to Gottlieb or fellow AIDS researcher and co-author, Dr. Joel Weisman.

Gay San Francisco Chronicle reporter Randy Shilts dubbed Weisman “the dean of Southern California gay doctors” in his AIDS opus, “And the Band Played On.” In 1978, as a general practitioner in a North Hollywood medical group, Weisman treated a number of patients with strange diseases, including a gay man in his 30s who presented with an old Mediterranean man’s cancer, Kaposi’s sarcoma.

In 1980, Weisman opened his own Sherman Oaks practice with Dr. Eugene Rogolsky and identified three seriously ill gay patients with strange fevers, dramatic weight loss from persistent diarrhea, odd rashes, and swollen lymph nodes, all seemingly related to their immune systems. He sent two of those patients to Gottlieb, a young UCLA Medical Center immunologist studying a gay male patient with pneumocystis pneumonia and other similar mysterious symptoms, including fungal infections and low white blood cell counts.

“On top of these two cases,” Shilts wrote, “’another 20 men had appeared at Weisman’s office that year with strange abnormalities of their lymph nodes,’ the very condition that had triggered the spiral of ailments besetting Weisman and Rogolsky’s other two, very sick patients.”

Weisman later recalled to the Washington Post that “what this represented was the tip of the iceberg. My sense was that these people were sick and we had a lot of people that were potentially right behind them.”

There were other missed signs, such as the CDC getting increasing requests for pentamidine, used to treat pneumocystis pneumonia. Gottlieb says that after his first report, the CDC’s Sandra Ford confirmed that she was sending increasing shipments of Pentamidine around the country. “But I’m not sure any infectious disease doctor there knew or investigated why they were seeing a run on pentamidine or asked what that meant,” Gottlieb told the Los Angeles Blade. Later pentamidine became “the second line therapy for pneumocystis,” after Bactrim.

Pentamidine “caused kidney problems, so we didn’t like it. Eventually, aerosolized Pentamidine became one of the preventatives. We didn’t realize at first that pneumocystis would happen in multiple episodes. Like a patient would have pneumocystis, we treated, it would clear and they’d go home for a month and then they’d get it again. We didn’t learn until later that we had to do something to prevent recurrences. And that’s where aerosolized Pentamidine came in doing a monthly breathing treatment.”

Though being gay was highlighted as a high-risk factor, race was largely left out of reports until 1983, despite the fact that Gottlieb’s fifth patient in his June 5, 1981 CDC article was Black. Gottlieb remembers him as a previously healthy 36-year-old gay Black balding man named Randy, referred to him in April by a West Side internist.

But Randy’s race was not included in that first report, nor was the omission caught by the MMWR editors, probably, Gottlieb speculates, because they were focused on collecting disease data while they struggled to save their dying patients. Gottlieb views the absence of race “as an omission and as an error” because demographic data is “good form as a doctor because it is important.” If race was not included in the MMWR, it was an unconscious omission.”

Karen Ocamb is the Director of Media Relations for Public Justice, a national nonprofit legal organization that advocates and litigates in the public interest.

The former News Editor of the Los Angeles Blade, Ocamb is a longtime chronicler of the lives of the LGBTQ community in Southern California.

Editor’s note; The photo of a dying David Kirby in Ohio in 1990 by photographer Therese Fare was labeled by LIFE Magazine as the photo that changed the face of AIDS. To read the story and to see a gallery of addition photos visit here; (LINK)

This is Part 2 of a series on AIDS @40. Part 3 looks at Rep. Henry Waxman’s congressional hearing in LA and the creation of AIDS Project Los Angeles.